A chemical found in plants could reduce the symptoms of a rare muscle disease that leaves children with little or no control of their movements.

Scientists from the Universities of Edinburgh and Aberdeen found that a plant pigment called quercetin – found in some fruits, vegetables, herbs and grains – could help to prevent the damage to nerves associated with the childhood form of motor neuron disease.

Their findings could pave the way for new treatments for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) – also known as floppy baby syndrome – which is a leading genetic cause of death in children.

The team has found that the build-up of a specific molecule inside cells – called beta-catenin – is responsible for some of the symptoms associated with the condition.

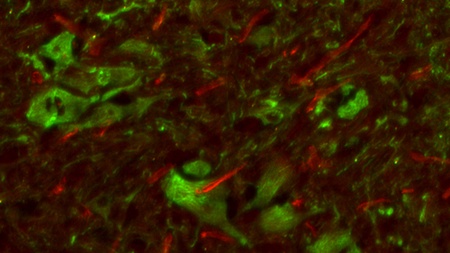

In tests on zebrafish, flies and mice, scientists found that treating the disease with purified quercetin – which targets beta-catenin – led to a significant improvement in the health of nerve and muscle cells.

Quercetin did not prevent all of the symptoms associated with the disorder but researchers hope that it could offer a useful treatment option in the early stages of disease.

They now hope to create better versions of the chemical that are more effective than naturally-occurring quercetin.

SMA is caused by a mutation in a gene that is vital for the survival of nerve cells that connect the brain and spinal cord to the muscles, known as motor neurons. Until now, it was not known how the mutation damages these cells and causes disease.

The study reveals that the mutated gene affects a key housekeeping process that is required for removing unwanted molecules from cells in the body. When this process doesn’t work properly, molecules can build-up and cause problems inside the cells.

Children with SMA experience progressive muscle wastage and loss of mobility and control of their movements. The disorder is often referred to as ‘floppy baby syndrome’ because of the weakness that it creates.

It affects one in 6000 babies and around half of children with the most severe form will die before the age of two.

The study is published today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Professor Tom Gillingwater from the University of Edinburgh, who led the study, said: “This is an important step that could one day improve quality of life for the babies affected by this condition and their families. There is currently no cure for this kind of neuromuscular disorder so new treatments that can tackle the progression of disease are urgently needed.”

Professor Simon Parson from the University of Aberdeen who was part of the international team lead by the University of Edinburgh, working on this project said “We have found a naturally occurring compound which treats some of the symptoms of SMA, which is important. We can now go on to develop more effective drugs to target this awful disease, for which there is currently no cure.”