The complex plumbing system beneath volcanoes has been revealed in the clearest detail ever, marking a 'major step forward' in our understanding of how they are formed and behave.

An international team of geologists has analysed the subsurface geology of the Erlend volcano in the Faroe-Shetland basin of the North Atlantic, allowing them to produce a detailed 3D map showing the volcano’s inner workings. It was once a small volcanic island that last erupted 58 million years ago, and is now buried and preserved underneath 1 km of sediment on the sea floor.

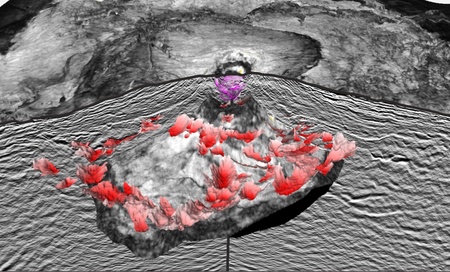

Instead of observing one large magma chamber beneath the volcano, the map reveals a complex amalgamation of smaller volcanic rock formations. It also suggests the long-assumed concept of a vertical, cylinder-like conduit that connects magma chambers and volcanoes – the ‘balloon and straw’ – is oversimplified.

The map is revealed as part of a paper published in the journal Geology, co-authored by geologists at the universities of Aberdeen, Adelaide, and Oslo. It is part of a project led by Faye Walker, a PhD student at Aberdeen and participant in the Natural Environment Research Council’s (NERC) Centre for Doctoral Training in Oil and Gas.

The team looked at seismic data provided by energy data company TGS, to understand the interaction of volcanic rock with petroleum systems in the far north of the Faroe-Shetland Basin, an area with significant gas reserves.

Aberdeen PhD student Faye Walker, who carried out the analysis of the 3D seismic data, said:

“Much of our understanding of how magma is moved around the Earth’s crust is still conceptual, but by producing the clearest images yet of the complex plumbing systems that underlie volcanoes, we can see things with our own eyes. This is a major step forward in terms of advancing the science around how volcanoes are formed and behave.”

Dr. Nick Schofield, from the University of Aberdeen’s School of Geosciences, added:

“Understanding the plumbing systems below volcanoes is usually really challenging, and to see them in the field the overlying volcano has to be eroded. This makes understanding the connection between the magma and understanding how it transits into the volcano difficult. This work has revealed this in detail.

“In terms of oil and gas exploration, the area in which the data was collected is potentially really important for the UK’s future gas needs as part of the energy transition, where gas has a vital role as a ‘carbon bridge’ leading to a greener future.

“Understanding the size of the magma chamber and the heating effect on the rocks which produce oil and gas will lead to better understanding of the area’s potential.”

Dr Simon Holford, from the University of Adelaide, said the findings could potentially play an important role in helping to predict future eruptions in active volcanoes.

“Understanding how molten rock makes its way from the chamber, though the Earth’s crust, to the volcanoes where it is erupted is one of the biggest challenges facing geologists”, he explained.

“Understanding how magma is stored prior to eruptions is essential in assessing volcanic hazards, but it is extremely difficult to directly observe magma chambers. Active volcanoes are challenging places to work and collect data, whilst ancient volcanoes and their underlying plumbing systems are rarely completed preserved.

“That is what makes our findings so valuable. These images reframe our understanding and suggest that models for predicting volcanic eruptions will need to be modified.”