Now, before going any further, I feel it is important to say, while I identify as a man, it is of the cisgender nature. This piece, and the month of June, is meant to elevate the lives, voices, and experiences of people that happen to not be like me. My role here is not to offer my experiences or views of the lived reality of trans and other LGBTQ+ individuals. Rather, it is to draw attention to those realities so that we can celebrate them together this month and reflect on how far we have come and, unfortunately, just how far we still have to go. I have tried to take reference from Dillon’s own autobiography, whenever possible, and scrutinized other sources for bias or transphobia, to the best of my ability. Language that no longer reflects current standards will be avoided but otherwise labelled with quotation marks. And finally, Dillon was a man by his own account and was given a name that he did not want and chose another. That is what he will be called here.

Laurence Michael Dillon was born in May of 1915, the second of two children, into the Baronetcy of Lismullen in Ireland. His mother, unfortunately, passed within days of childbirth, which left him and his older brother in the care of their two aunts in Kent, England. Their father later succumbed to pneumonia complicated by alcoholism in 1925, leaving them solely in the care of their aunts but with the advantages afforded them through their aristocratic lineage. Dillon went on to attend what is now St. Anne’s College in Oxford, becoming a distinguished rower and president of their boat club.

Upon graduating in 1938, he took work at a laboratory in Gloucestershire that conducted brain research. In 1939, Dillon sought the advice of a Dr George Foss who had been experimenting with testosterone (just recently synthesised for the first time in 1935) for treating excessive bleeding during menstruation. Foss said he would prescribe Dillon with testosterone on the condition that he seek a consult with a psychiatrist. This psychiatrist, betraying both trust and professionalism, went on to out Dillon as trans to his supervisor at the lab, forcing Dillon to relocate to Bristol and take a job at a local garage. By this time, Dillon was able to see the effects of the testosterone in the growth of a beard and packing on muscle. He worked as both a driver and as a nightwatchmen for the garage, stationed as a lookout for fires during the tumultuous bombing raids that Bristol endured during the early years of World War II. Although the work was far from ideal, and his co-workers offered little but senseless bullying, Dillon was able to form a friendship with a young man named Gilbert Barrow. Barrow worked alongside Dillon for only a short time before he was called to serve in the Navy, but Dillon remembers that time fondly:

“Then I asked him if he knew since he had never given any sign but always treated me as if I were another fellow. ‘Oh yes,’ he said, ‘They told me the first day, but I told them I would knock the block off anyone who tried to be funny about you. I also said you really were a man and that had them puzzled. They didn’t know what to believe then.’ ‘A faithful friend is a strong defense and he that hath found one hath found a treasure.’ So said Solomon in his wisdom. My debt to G. [Gilbert] for this loyalty in my darkest hour could never be repaid although I did my best in later years.” – Out of the Ordinary, pg. 93

Dillon continued his journey in Bristol, unfortunately, becoming injured after a hypoglycaemic spell and spending several days in hospital. However, it would prove fortuitous as it was there that he met a plastic surgeon, probably Dr Geoffrey Fitzgibbon, who agreed to perform a mastectomy for Dillon. Dillon had been vexed by his chest and after the surgery remarked,

“I was delighted with this operation when I had recovered from it. At last I was rid of what I hated most. I sat out on the verandah letting the sun help to heal the incisions.” – Out of the Ordinary, pg. 100

This same surgeon remarked that Dillon should then reregister himself so that his birth certificate and other identity cards would be the appropriate gender. He was able to do so with the signature of a doctor and a family member, one “more modern than anyone else […] she readily obliged to my delight[…]” (Out of the Ordinary, pg. 100). So, in 1943, Dillon was able to take on the name Laurence Michael. The final service this plastic surgeon provided was to introduce Dillon to his mentor, Sir Harold Gillies, a pioneer in plastic surgery and one who essentially founded the field for the benefit of helping war-torn soldiers regain a sense of normalcy through reconstruction. Dillon met with Gillies to discuss the possibility of further surgery and Gillies agreed with the caveat that it would be some time before he could, as the ongoing war still saddled him with a multitude of soldiers to mend, which had Gillies operating for as long as 20 hours per day. While he waited for Gillies’ schedule to clear, Dillon had been inspired by an acquaintance who was a doctor to pursue his own medical degree. Through some creative collaborations with a former tutor at Oxford, Dillon was able to get his prior degree certificate in the correct name and enrol at Trinity College, Dublin.

Michael Dillon at about age 35 with his aunt © Liz Hodgkinsons

In 1945, with the war ending, Dillon was able to meet with Gillies to finally embark on what would amount to a total of 13 surgeries over the course of four years. Dillon started his medical education that same year, attending lectures during term time and attending the operating theatre during breaks. This gave him the unique experience as an emerging clinician of what it meant to be a frequent patient,

“Thus I came to know hospital life from the patient’s point of view as well as the doctor’s, an advantage which many of my colleagues lacked, and lacking were unaware how genuine were the complaints from the bed very often with which they lacked the sympathy that experience would have given them.” – Out of the Ordinary, pg. 105

Over those four years, Dillon went through what would be the world’s first Phalloplasty, at least so far in being utilised as part of someone’s transition. Gillies’ technique would become the standard for that surgery for decades to come and he would also pioneer surgical techniques used by trans women seeking surgical components to their transition. Gillies seemed to take great pride in his work and gained the respect of his patients, including Dillon. On Gillies’ death in 1960, Dillon received word of his passing and remarked,

“His one aim had always been to make life tolerable for those who either Nature or man had ill-treated without regard to conventional views and to many a one he must have given renewed hope and a new start.” – Out of the Ordinary, pg. 187

Dillon would himself qualify as a doctor in 1951 and would go on to join the Merchant Navy as a surgeon. He sailed with the Navy for six years, traveling the world for months to years without setting foot in England or Ireland. It’s difficult to say what the allure was of these long absences away from home, but some biographers point to a difficult relationship between Dillon and one Roberta Cowell as being a contributing factor. Cowell too sought surgery as part of her transition and was the first to undergo the surgical techniques pioneered by Gillies mentioned previously. She had been connected with Gillies through Dillon, and had come to seek out Dillon in her search for the author of a seminal work on the ethics of gender transition. This book, Self: A study in ethics and Endocrinology, is, perhaps, one of Dillon’s most notable and enduring legacies. Dillon began work on the book whilst still in the midst of a bombarded Bristol. The book is considered to be one of the first psychomedical works to discuss trans identity and transitioning and to separate it from homosexuality, with which it was often conflated. Generally, Dillon laid out arguments for the medical treatment of those experiencing what would later be called “gender incongruence”, the mismatch between the sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity. He discusses the failings of the purely psychotherapeutic treatment endured by those striving to align body with mind. As Dillon puts it,

“Surely, where the mind cannot be made to fit the body, the body should be made to fit, approximately, at any rate to the mind, despite the prejudices of those who have not suffered these things, yet to suffer which they so readily condemn others.”-Self: A study in ethics and Endocrinology, pg. 53

While Dillon did not remark explicitly about his own medical treatments as a trans man within the pages of Self, Cowell seems to have intuited that some of these insights came from personal experience. The two formed a close relationship and Dillon served as a source of support for Cowell during her transition. Dillon even went so far as performing a part of Cowell’s surgical transition, despite not yet being qualified as a surgeon, because it was deemed illegal to perform in Britain. Their relationship, unfortunately, soured as time went on, partly due to Dillon’s desire for it to be romantic. Cowell did not reciprocate this desire, turning down a marriage proposal from Dillon in 1951.

Roberta Cowell in 1958

Dillon enjoyed his years in the Merchant Navy, even publishing a book of poems called Poems of Truth in 1957. However, his Navy days came to an abrupt end when tabloid journalists tracked him down for comments on a piece that had outed him as a trans man. Discrepancies in the records of his family’s lineage tipped off the press and gossip soon circulated. Dillon’s world came crashing down that March of 1958. So carefully had he maintained himself and yet, “Here was the end of my emancipation!”, as Dillon put it. Dillon’s sympathetic shipmates kept unscrupulous tabloid reporters at bay whilst Dillon contemplated his next move. Dillon decided to take refuge in India, letting his Captain and Medical Superintendent know that he would disembark in Calcutta and be there until the press around him had quieted down.

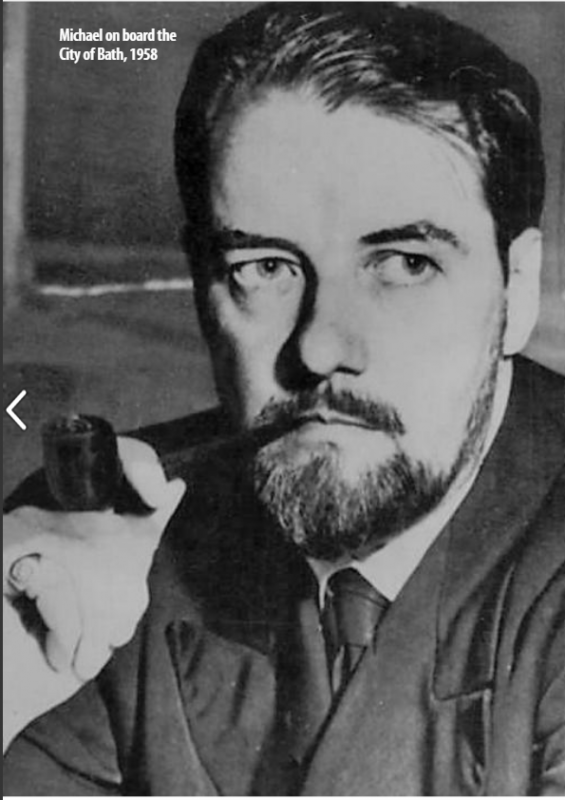

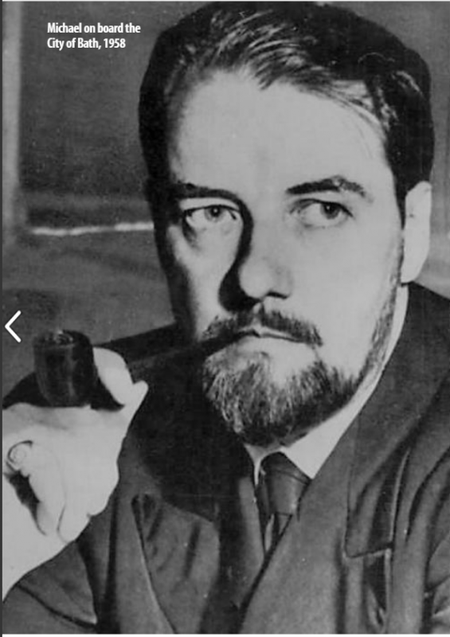

Dillon during his time in the Navy

Dillon arrived in India in the summer of 1958 and soon found himself drawn to the study of Buddhism. He met Sangharakshita (Dennis Lingwood), a British Buddhist, in Kalimpong, and decided to pursue ordination and took the name Sramanera Jivaka, after the Buddha's physician. During this time, Dillon wrote several books on Buddhism for English audiences and became deeply involved in the spiritual path of Buddhism. Internal conflicts within Kalimpong, namely Sangharakshita refusing to fully ordain Dillon, led Dillon to pursue Tibetan Buddhism in Ladakh. Unfortunately, Dillon’s health soon declined and he passed away in hospital on 15 May 1962, at the age of 47.

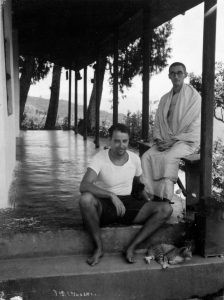

Left photo: Dillon (left) and Sangharakshita (right) in 1958 at a Buddhist monastery in Kalimpong, India © Uddiyana Trust

Right photo: Dillon (4th from left) at Rizong Monastery in Ladakh, India

Dillon’s autobiography, Out of the Ordinary, was not published until 2017. The manuscript had been sitting in storage of Dillon’s publisher and possibly suppressed for publication in his own time by his older brother. Luckily, scholars Jacob Lau and Cameron Partridge have been able to bring Dillon’s account of his life to the public. They did so saying, “that the memoir has thus far remained unpublished has been a loss to multiple readerships, not least to an increasingly empowered transgender community eager to engage with the historical sources of its pioneers.” Dillon seemed to be unsure or uncomfortable telling the store of his “changeover”, but it seems that he wanted to share his history on his own terms and contribute to a larger acceptance of those like him. In the author’s introduction to his memoir, written two weeks before his death, Dillon recounts that,

“The conquest of the Body proved relatively easy. But the conquest of the Mind is a never ending struggle and it still goes on. Yet it is the sole purpose of our life on Earth. Not the pursuit of happiness or pleasure, not to leave our offspring socially better off than we were, nor yet to amass money or power nor take our evil to other planets [added by hand: “under the guise of Progress”]. But to evolve spiritually, no more, no less.” – Out of the Ordinary, pg. 30

Dillon’s life and the lives of other pioneering individuals within the trans and other LGBTQ+ communities serve to highlight the richness and complexity of the human experience. We are lucky to be able to read these accounts, as doubtless others are now lost to history through the malicious weight of bigotry. Dillon was simply trying to pursue a life that aligned with his truth, to align body and mind, as he said. That he persevered in the face of constant setbacks, betrayals of trust, the pressures of rigid sexual and gender identity, and other barriers to pursuing that truth, is testament to his strength and resolve. As we celebrate Pride this month, nearly 60 years since Dillon’s death, I hope that these barriers become fewer and more surmountable for contemporary trans individuals. We all have a responsibility in making that happen. We should know these stories, we should sympathise with the struggles, celebrate the successes, and recognise the humanity in all of it. No one should have to fight for their place in the world, it is already uniquely and immutably theirs. Trans rights are human rights.

Thank you for reading. I encourage you to read Dillon’s autobiography, which I was able to find here: Out of the Ordinary - Transreads.org. I have very much given a cursory summary of his life here and it is afforded the proper length and narrative clarity in that piece, especially with the foreword by the editors. I’d also encourage you to look into Sir Harold Gillies, as I found him a fascinating person. His two volume work, The principles and art of plastic surgery, is available in the Medical Library (or at least it will be once I return it).

The Students’ Union has forums such as the LGBTQ+ forum, Trans Students’ Forum, and the Women & Non-Binary Students’ forum.

For other advice and support outside the Uni, visit https://switchboard.lgbt or https://www.stonewall.org.uk/.

Sources

- Self: A Study in Endocrinology and Ethics (1946) by Michael Dillon

- Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Gender and Spiritual Transitions (1962; published 2017) by Michael Dillon/Lobzang Jivaka

- https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/blog/bristols-remarkable-trans-pioneer-michael-dillon/

- https://blog.bham.ac.uk/historybham/lgbtqia-history-month-trans-pioneers-michael-dillon-roberta-cowell/

- The Bristol Magazine, July 2020, Issue No. 191, pg. 42.

- https://www.gires.org.uk/resources/terminology/

i get it now :)

It agree, it is the remarkable answer

You have hit the mark. Thought excellent, I support.

There is a site, with an information large quantity on a theme interesting you.