White Feelings and Our Colonial Heritage

Dr Eloise Grey graduated with a PhD in Scottish History from Aberdeen during lockdown 2020. In this blog post she considers the history of the emotional responses of white British people to slavery and their colonial past and proposes that we, as white Scots and Brits, learn to live with feelings of discomfort. She explores how feelings are embodied legacies of history and considers whether focusing on whiteness historically is one way of uncovering the history of racism in the UK and how feelings have become embedded and unconscious.

As those of us who are white British or Scottish confront our colonial past in the light of waves of protest and counter-attack, emotions run high.

The renewed focus on the need to re-examine this important period of our history, brought about by the Black Lives Matter movement, parallels the research I conducted for my PhD.

My work examined the emotional culture of imperial families of the North East of Scotland during the eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Gentry families, whose sons typically spent formative years at the University of Aberdeen, were heavily involved in imperial spaces.

They may have enslaved Africans in the Americas, they may have serviced such plantation economies as doctors or teachers, been employed by the East India Company or joined the British Army, for example, to support settler colonists in countries such as modern Australia.

My work shows how emotional culture served the economic and social status of families in the ways in which they used affection to maintain kinship networks and trained their children to develop the right feelings.

This enabled them to find marriage partners, employment opportunities and cohere as a social group, in a period when imperial spaces offered opportunities. In my work I argue that Scottish men, and their families at home, became what they were, in part, because of anxieties about colonial others.

‘Others’ are defined by their relation and difference to those with greater, often hegemonic power, in this case white Western European.

Recent events have brought a range of emotions into the history we are living now. How emotions become contested is one way in which historical change happens and is part of my research. A clear example of this is when Boris Johnson talks about ‘wetness’ in relation to critiques of the British Empire, thus silencing important conversations using an emotional challenge.

This ‘wetness,’ a feminised judgement on a kind of softness, or humanitarian feeling, stands in contrast to a form of courage that is offered as necessary in order to be patriotic and to ignore our colonial past. Others point to the need to be more open about our past and the Scottish government has made a commitment to ‘ensure people in Scotland are aware of the role Scotland played (in the empire) and how that manifests itself in our society today’.

In eighteenth century Aberdeen feelings about empire and enslavement were part of contemporary discourse. Empire was present in the lives of Scots of all classes. Aberdeen and shire produced and exported a range of goods to service the colonial elite in the plantation economies of the West Indies.

To those who argue that chattel slavery was normal then, they would do well to read up on Aberdonian critics of slavery such as James Beattie and his peers in the Aberdeen Philosophical Society. Their ideas of universal humankind were taken up by the abolitionist movement. Silvia Sebastiani argues that Beattie ‘educated generations of Aberdonian students in humanitarian principles’. Such principles came with a Scottish Enlightenment feeling culture that refinement and sympathy became signifiers of civil development.

Herein lay the problem. This feeling culture was one of differentiating white colonial players from their colonial others, and placing groups on a hierarchy of human diversity, whilst still arguing for a common humanity. Some of this manifested itself by colonial elites stressing their humane treatment of enslaved Africans and propagating the narrative that they were in fact happy. Abolitionists in Britain deployed feelings of sympathy towards enslaved people for their cause.

This was what Ramesh Mallipeddi calls ‘spectatorial sympathy’, in which seemingly well-meaning white people circulated gruesome images of enslaved Africans. These images of victimhood continued the dehumanisation process anew. These elite feelings served to decentre colonial others from the conversation between white people. In fact, as scholars such as Priyamvada Gopal argue, it was not just victimhood but contestation, rebellion and revolts of enslaved Africans and the colonised that shaped the need by Europeans to form a narrative of difference and occupation.

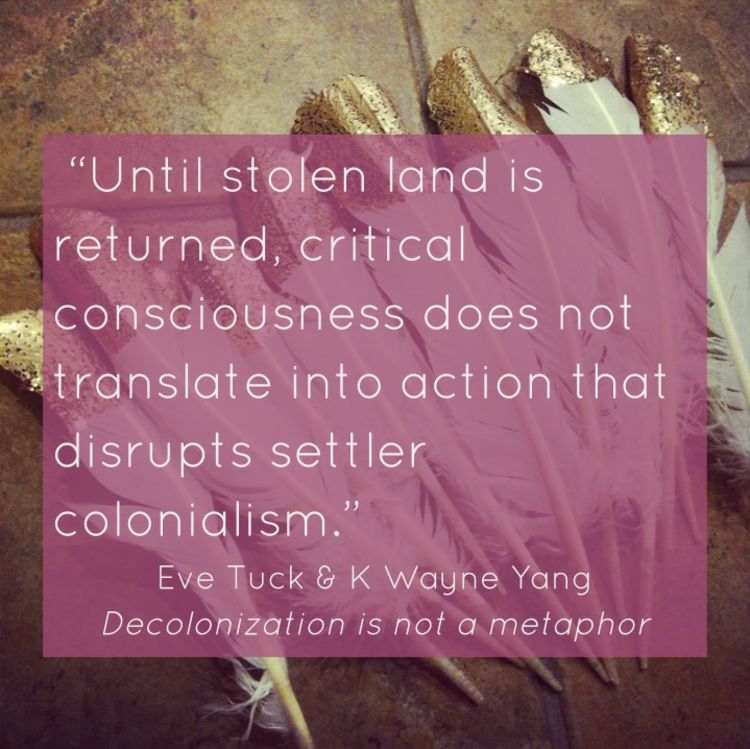

Returning to today, if ‘wetness’ is not a useful feeling then what feelings are useful and to whom? We could do well to read Eve Tuck and K.W Yang’s important essay ‘Decolonisation is Not a Metaphor’, who describe a ‘fantasy of mutuality based on sympathy and suffering’ as a white coloniser ‘move to innocence’ and a way of reconciling guilt or complicity without conceding any space.

The Scottish Government’s intention to have a more honest approach to the past may fall victim to this sentiment. However, a more concrete desire to consider how such legacies manifest today shows signs of hope

Sugar plantation in the British colony of Antigua, 1823 (by William Clark - provided by the British Library from its digital collections).

Sugar plantation in the British colony of Antigua, 1823 (by William Clark - provided by the British Library from its digital collections).

James Beattie, Scottish scholar and writer

James Beattie, Scottish scholar and writer

As we approach Black History Month, we could remind ourselves firstly that the other eleven months are White History, and that the individual lives of colonial others were central to our white histories, yet obscured from view.

These lives were interconnected and our feelings, so intensely implicated in how we create groups, differentiate ourselves from others, and respond to historical events, are too. As white Scots it might be time to take a step back, give space to the past and the pain, violence and loss that continues to be felt by some whose ancestors were colonised or enslaved.

We need to resist the ‘moves to innocence’; instead decentre ourselves, listen to the feelings and anger our national story has produced, and learn to sit with discomfort.