Trust in the future of MRI

A visit to the birthplace of MRI, 40 years on

A visit to the University of Aberdeen’s Biomedical Physics laboratory is a curious experience.

In an unassuming building almost hidden in the shadow of the Institute of Medical Science, there is little to indicate that inside, the future of MRI technology is being fine-tuned by “scientific descendants” of the team that helped birth the original technology 40 years ago.

This is a place where physics and medicine collide in a smorgasbord of soldering irons, racks of components and small monitors displaying symbols and diagrams as if from another planet.

It is here that the world’s first full-body MRI scanner was designed and built by Professor Jim Hutchison and Dr Bill Edelstein under the leadership of Professor John Mallard using “spin warp” technology – the pioneering technique now used in all modern MRI scanners. In 1980 they successfully scanned their first ever patient.

Professors Mallard and Hutchison pictured with a Mark 2 scanner and the Aberdeen MRI Group

Professors Mallard and Hutchison pictured with a Mark 2 scanner and the Aberdeen MRI Group

Prof. Mallard (third from left) and the Aberdeen Magnetic Resonance Group

Prof. Mallard (third from left) and the Aberdeen Magnetic Resonance Group

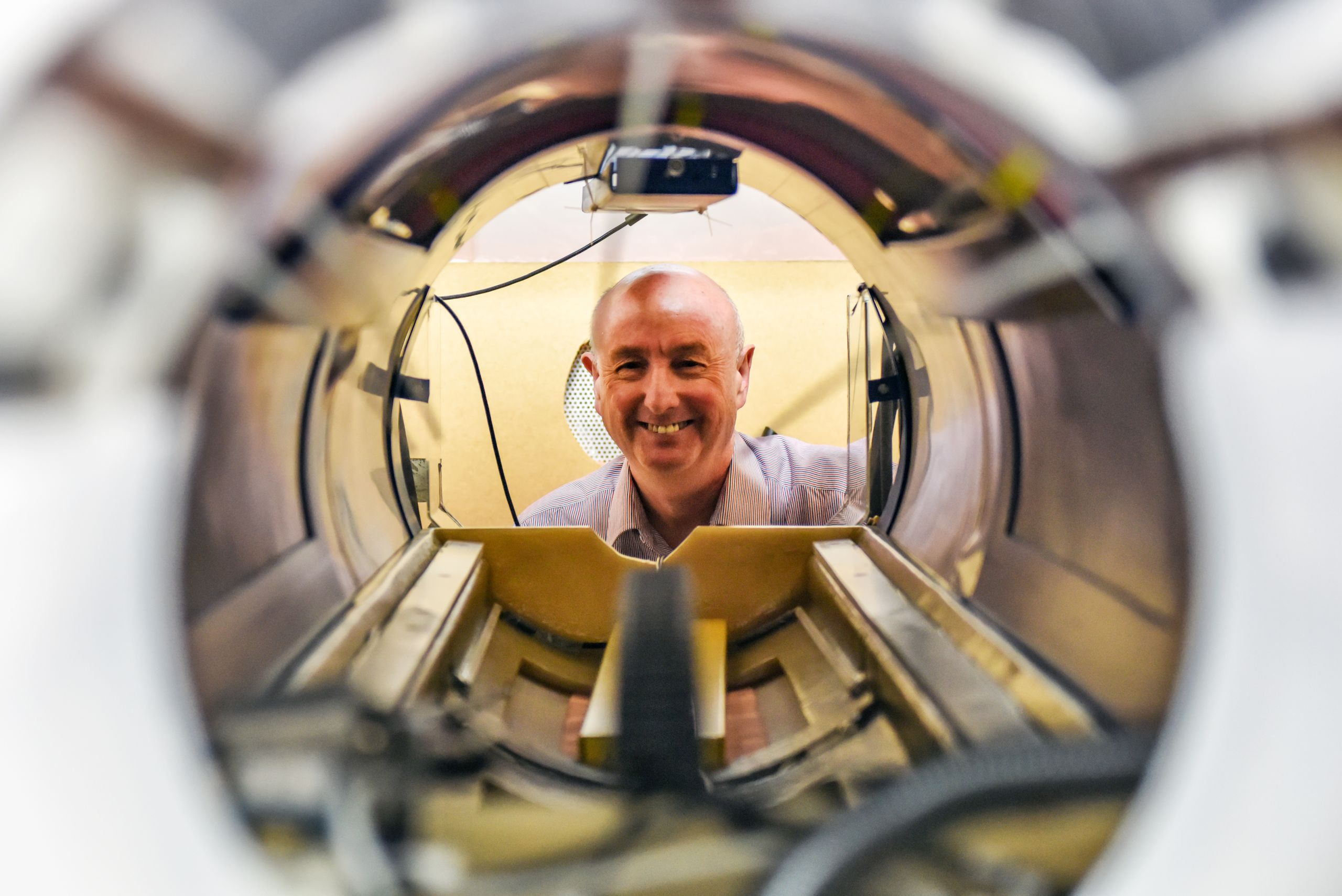

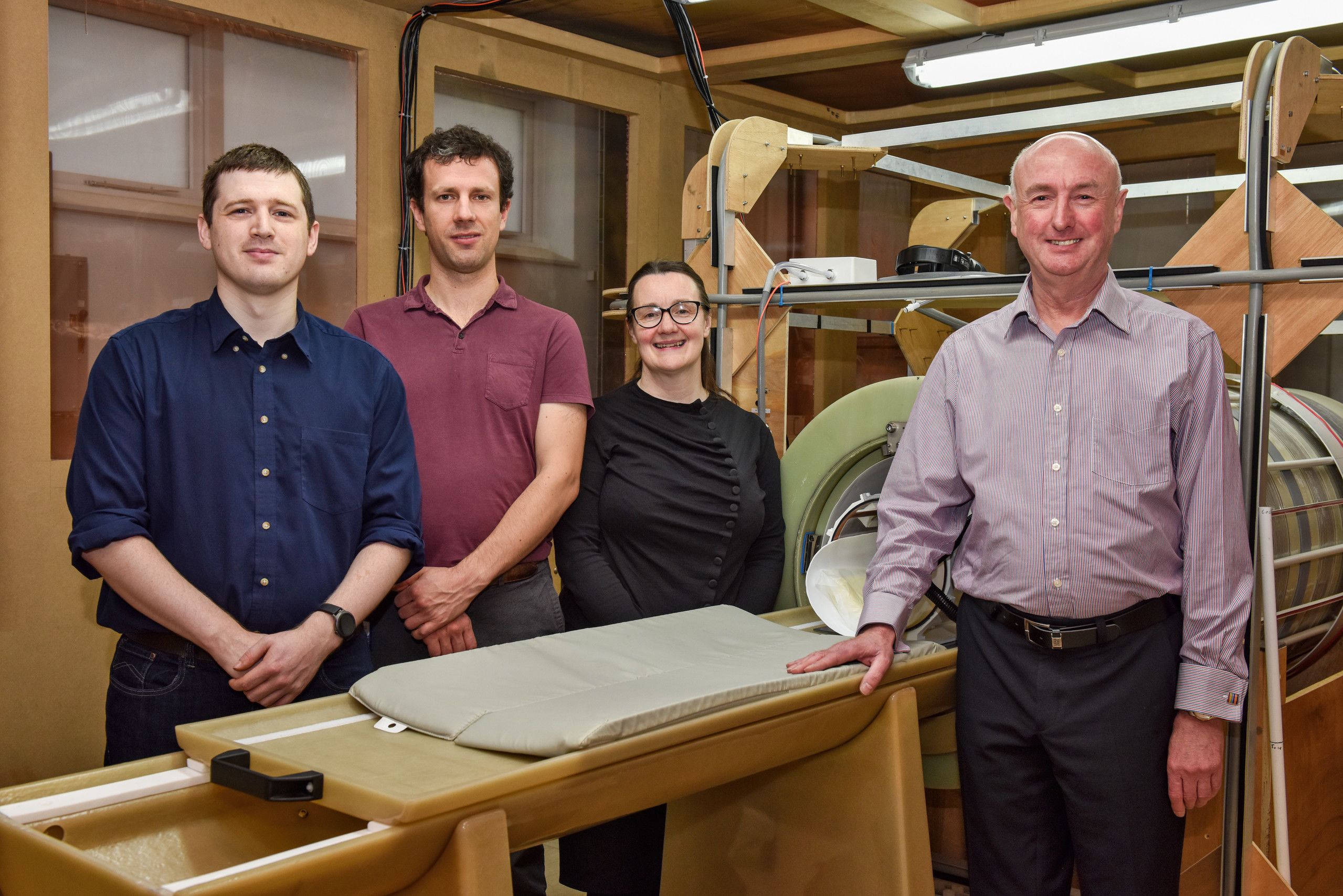

Prof. Lurie and colleagues at the Fast field-cycling MRI facility

Prof. Lurie and colleagues at the Fast field-cycling MRI facility

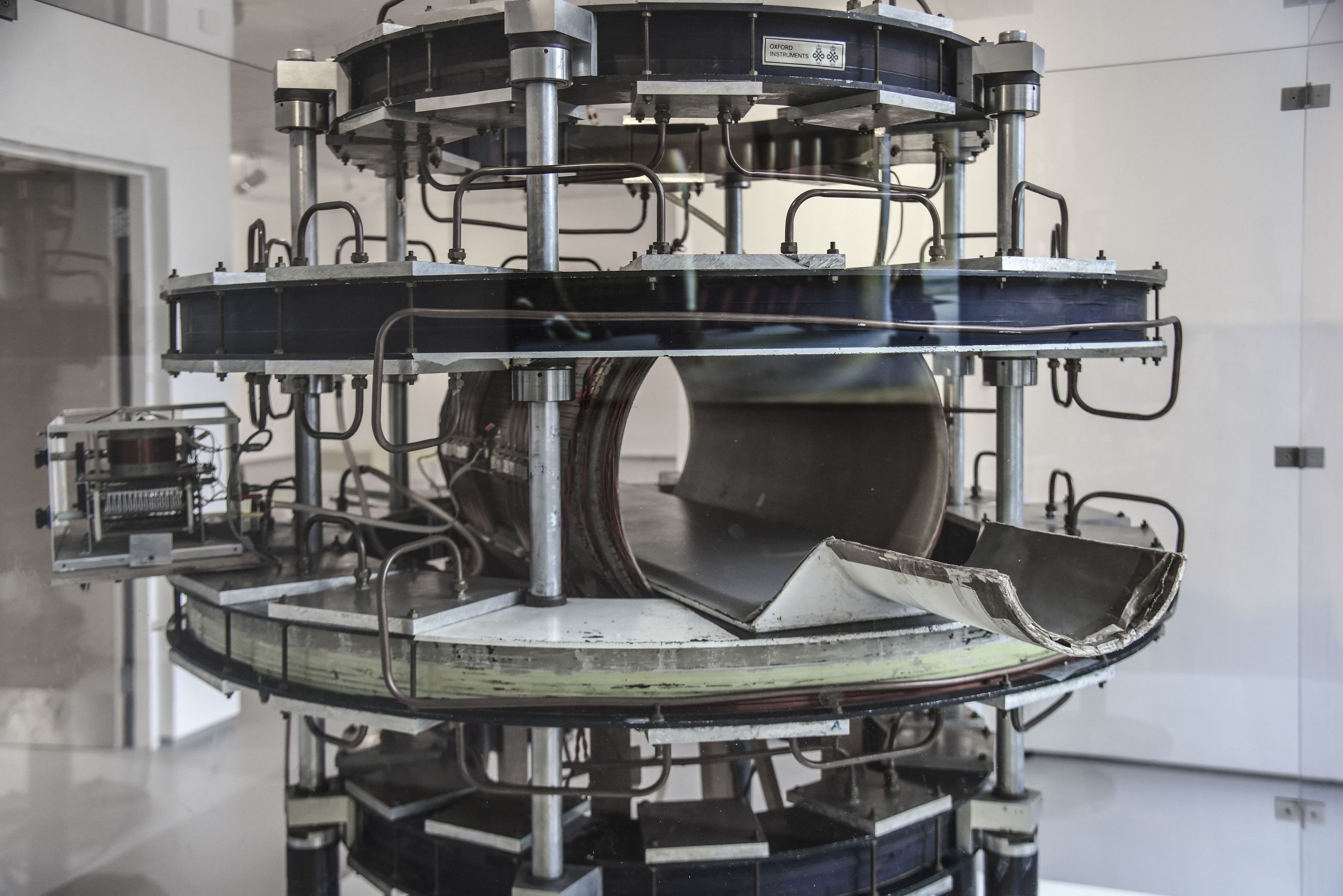

Today the MRI team is led by Professor David Lurie, who was a junior member of staff under Hutchison and Mallard, who passed away in 2018 and February 2021 respectively. In the heart of his laboratory sits a large, copper mesh-clad box, housing the world’s first Fast Field Cycling (FFC) scanner.

It is within this copper cube (the copper prevents outside signals interfering with the scanner’s readings) that the technology has been refined. Described by Professor Lurie as “like 100 MRI scanners in one”, it is capable of identifying disease earlier and in more detail than existing scanners.

The theory behind the technology is not new – it was first discussed during Professor Hutchison’s reign – but it has taken this long to bring to fruition.

Thanks to a generous £600,000 donation from The Mary Jamieson and John F. Hall Trust, a new purpose-built imaging suite will house the next iteration of the FFC MRI scanner. Its location within Aberdeen Royal Infirmary will make it easy for patients to be scanned in a conventional MRI scanner immediately before or after an FFC scan, thus revealing what extra diagnostic information FFC can provide and allowing doctors and scientists to make a direct comparison with the conventional imaging technology.

While the Covid-19 pandemic has seen the project delayed, Professor Lurie is hopeful of getting the imaging suite fully operational during 2022. And although yet to be proven, the FFC scanner might be able to play a role in Covid-19 treatment, as it may be better than conventional MRI at scanning the lungs and assessing the impact of the virus on the body.

Professor Lurie said: “We are really excited to be entering this next, crucial stage of the development of FFC and we are extremely grateful to the Mary Jamieson Hall and John F. Hall Trust for supporting the creation of this new imaging suite and funding a crucial lectureship post.

“The new imaging suite will allow us to scan a much wider range of patients than before and its location allows us to draw immediate direct comparisons with existing MRI scanners on the same patient.”

The legacy of Professor Mallard’s team is evident in the enormous contribution that MRI has made to global healthcare, and now Professor Lurie and his team are writing the next chapter in the story of this extraordinary life-saving technology.