The airbrushing from history of the Aberdeen insulin pioneer

In 2021, the world celebrates the centenary of the discovery of insulin – a breakthrough which transformed what is now known as Type 1 diabetes from a death sentence to a manageable condition.

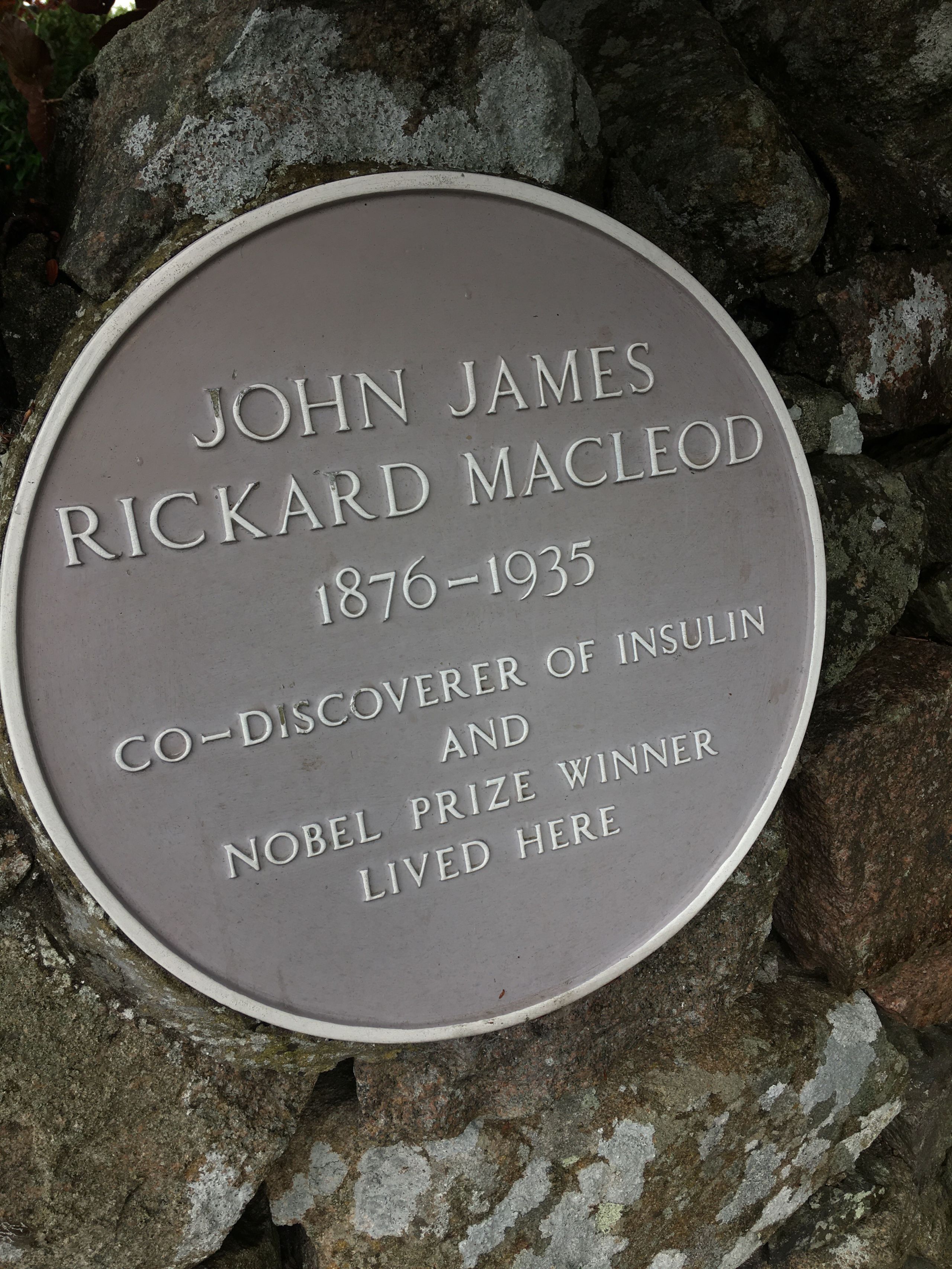

But the name of Aberdeen graduate JJR Macleod has not always been at the forefront of commemorations for one of the most significant advancements in medical science.

Despite being jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for his work, Macleod’s name became mired in accusations that he had stolen ideas and claimed credit where it was not deserved.

Macleod, who spent his later years back in the University of Aberdeen as Regius Professor of Physiology, saw his reputation tarnished and when he left Toronto, where the breakthrough was made, he is said to have been seen shuffling at the station and explained, ‘I’m wiping away the dirt of this city’.

While Macleod’s name was distanced from the breakthrough during his lifetime, the work of a Canadian historian in retelling the story of insulin sixty years later dispelled many of the myths contained within most popular accounts, which attribute the discovery to two inexperienced Canadian researchers, Frederick Banting and Charles Best.

His investigations detailed a far more complex, if no less acrimonious, story, revealing that the discovery was indeed a team effort for which Macleod rightfully earned his credit.

We explore how JJR Macleod became the forgotten man of insulin discovery – so much so that even the centenary date reflects the account which omits much of his contribution - and examine the efforts to restore his place in history 100 years on.

A brilliant young scientist

John James Rickard Macleod, son of a clergyman, was born near Dunkeld in 1876. At age seven his family moved to Aberdeen on his father’s appointment as minister at John Knox Free Church.

After displaying his academic prowess at Aberdeen Grammar School, he secured a place to study medicine at the University of Aberdeen graduating with Honourable Distinction in 1898.

Upon graduation, Macleod set his sights on a career in academic physiology, working in a laboratory rather than a clinical setting. Winning a travelling scholarship allowed him to begin his research career in Leipzig where his studies involved him in the evolving field of physiological chemistry.

Macleod’s research reputation grew quickly and in 1903, 10 days short of his 27th birthday, he set sail for the United States where he had been recruited by a University in Cleveland to become Professor of Physiology.

Several years of research on carbohydrate metabolism led to publication of his 1913 monograph Diabetes: Its Pathological Physiology and by 1918 the first edition of his definitive textbook Physiology and Biochemistry in Modern Medicine was published.

His credentials as a leader in developing training and education, as well as his reputation and prowess as an academic physiologist, attracted the attention of the progressive medical school at the University of Toronto, which headhunted him later that year.

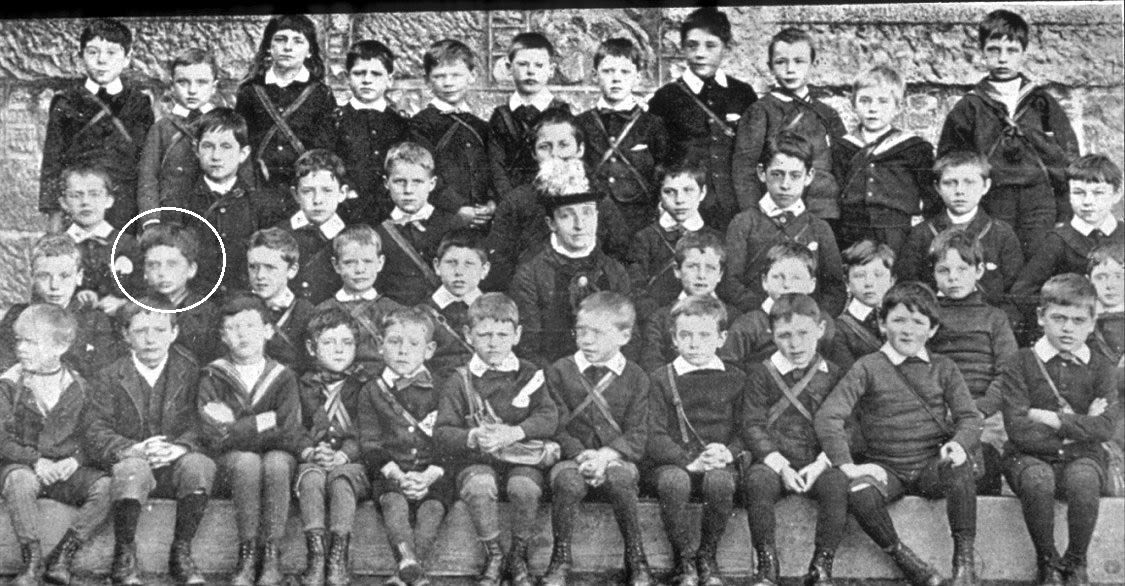

Class III Senior Initiatory Department, Aberdeen Grammar School 1885-6 showing J. J. R. Macleod.

Class III Senior Initiatory Department, Aberdeen Grammar School 1885-6 showing J. J. R. Macleod.

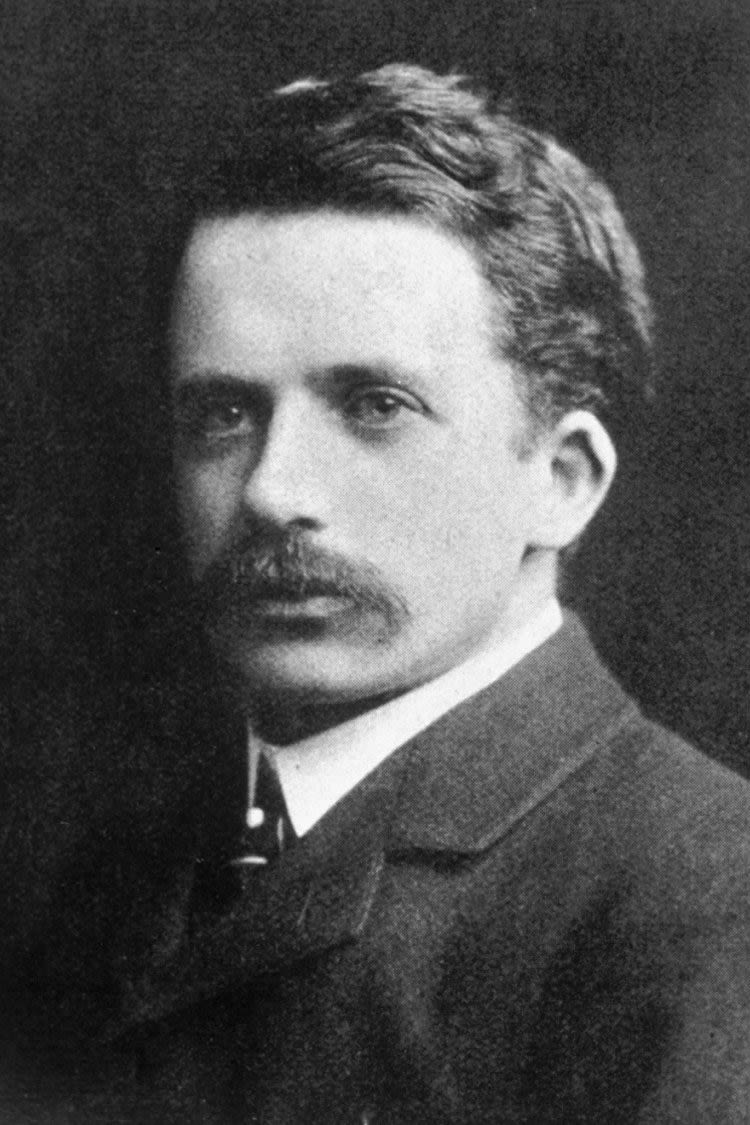

Macleod in 1906 when Professor of Physiology, Western Reserve University, Cleveland. (Reproduced from medics book IV The Reserve 1906 by permission of Case Western Reserve University.)

Macleod in 1906 when Professor of Physiology, Western Reserve University, Cleveland. (Reproduced from medics book IV The Reserve 1906 by permission of Case Western Reserve University.)

Banting, his eureka moment and the seeds of conflict

In November 1920 Macleod met a young physician named Frederick Banting. Banting, who had no experience in research or in diabetes, had been told to seek out Macleod as a leading expert in diabetes to progress an idea he is said to have come up with late one night after reading an article on the pancreas.

While not fully understood, there was growing evidence that pancreatic disease may have a link to diabetes, especially after it had been shown some years earlier that removal of the organ in experimental dogs produced features of the condition.

At this time there was no cure for what is now known as Type 1 diabetes. The only temporarily effective treatment was a form of supplemented starvation involving severe calorie restriction. The metabolism could cope for a time with so little nutrition but at a cost of progressive weight loss and muscle wasting so a diagnosis of diabetes left those afflicted with an inevitable and short death sentence.

Banting had an idea that tying off the pancreatic duct and keeping the animal alive for several weeks may leave tissue behind containing something useful to diabetes treatment.

Macleod agreed to give Banting laboratory space and he arrived in May 1921 to begin his experiments.

Macleod demonstrated the surgical technique necessary for the removal of the pancreas and assigned physiology graduate Charles Best to assist him as he had developed expertise in glucose analysis.

In the summer Macleod departed for a visit to his native Scotland and it is during this absence that retired diabetologist Ken McHardy, who has spent many years researching Macleod, says the ‘rot set in’ in the relationship between the researchers, which would eventually see Macleod’s reputation blackened.

“By the end of July and at the expense of quite a number of dogs, Banting and Best had been able to produce pancreatic extracts that lowered glucose in diabetic dogs,” said Dr McHardy – an honorary senior lecturer at the University of Aberdeen who spent more than 20 years as a consultant with NHS Grampian.

“In early August they wrote to Macleod in Scotland setting out what they had found but their enthusiasm clashed with the more methodical and scrupulous nature of their highly experienced and internationally respected senior colleague.

“He directed them to repeat various processes to eliminate alternative possibilities for their results.

“He also indicated that they had been remiss in not conducting autopsies on more of the dogs.

“It is likely that this direction to sound scientific methodology was not well received and divisions which would only intensify began.”

The accelerating pace of the research needed more hands so in early December a visiting professor of Biochemistry, James Collip, joined the team; it was thought that his experience in working with extracts would be particularly useful.

Dr McHardy adds: “By this stage it had become apparent that Banting’s duct-ligation procedure had been, all along, an unnecessary step adding delay and complexity. Collip set to work on purifying extracts from whole fresh bovine pancreas obtained from the local abattoir.

“As previously suggested by Macleod, alcohol was used for the extraction process. Collip used sequentially higher concentrations to eliminate impurities until, at 95%, the active principle itself was precipitated: Collip was effectively the first to actually see what would come to be known as insulin.

“Banting, always anxious to prove that he had found the cure, and soon threatened by Collip’s rapid progress, gave his extract orally to a diabetic patient in mid-December; unsurprisingly it had no effect.

“In early January 1922 he pressed for his extract to be tried again – this time by injection. Once again it failed. But by January 23, the purer form developed by Collip was ready and this time the patient, Leonard Thompson, responded well.”

The extract, later formally named insulin, immediately saved lives in Toronto and in due course round the world but despite the initial success, there remained many hurdles to overcome. Macleod once again played a key role, in directing Collip in developing a standard for assessing the potency of extracts, in facilitating links with industry to scale-up production and in managing expectations to cope with the clamour for supplies.

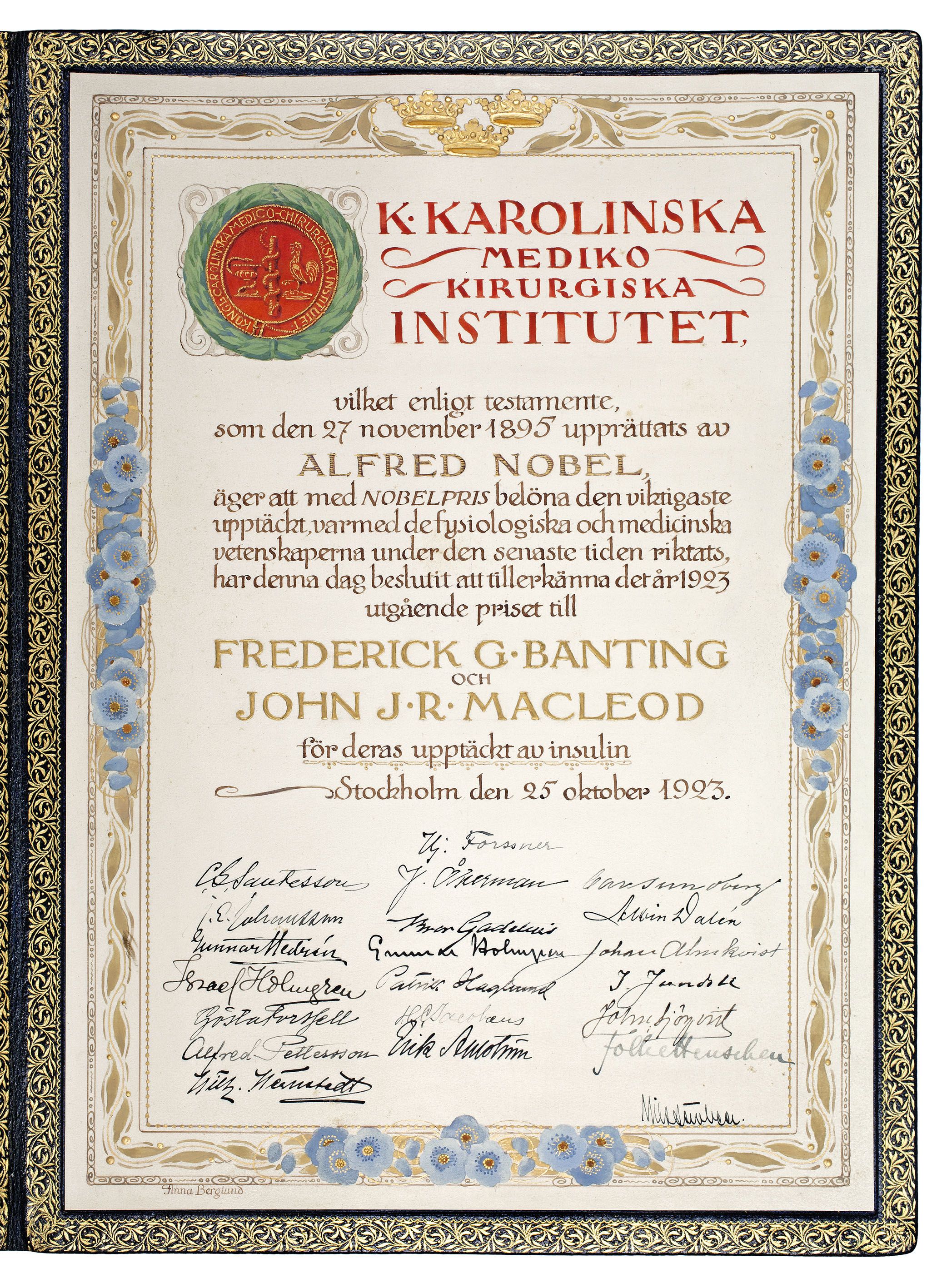

The Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine awarded to Banting and Macleod

The Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine awarded to Banting and Macleod

Frederick Banting pictured in 1941, shortly before his death

Frederick Banting pictured in 1941, shortly before his death

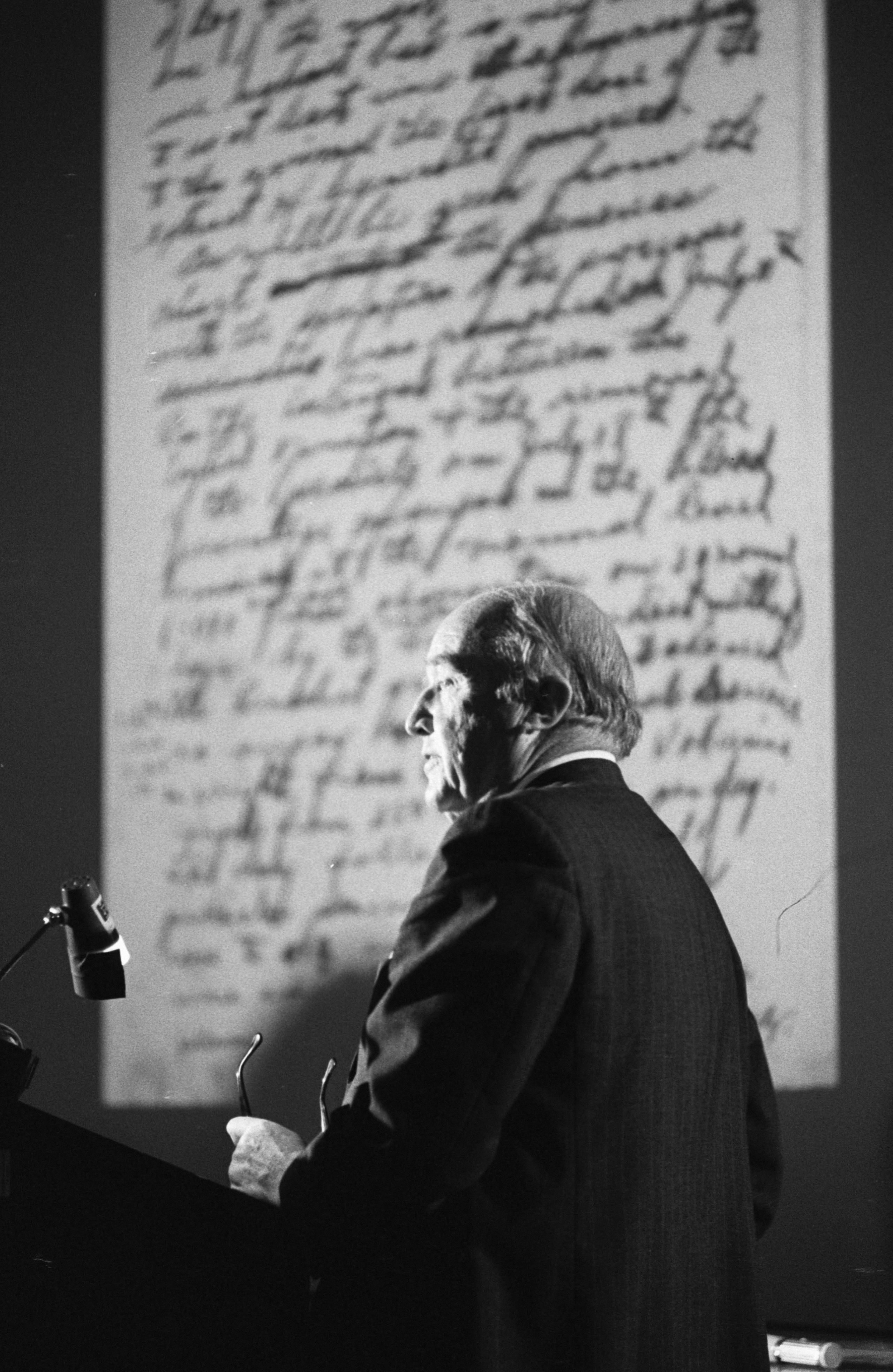

Charles Best giving a lecture on insulin discovery in January 1975 (University of Toronto Archives and Robert Lansdale, photographer)

Charles Best giving a lecture on insulin discovery in January 1975 (University of Toronto Archives and Robert Lansdale, photographer)

The erosion of Macleod’s name in insulin discovery

1923 marked a high point for Macleod in the insulin story when he and Banting were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, splitting their award money with Collip and Best respectively.

Banting also shared his anger - and his views that Macleod’s share was ill deserved with his friends and one, his former teacher Dr William Ross, organised a successful campaign in Canada to have Banting recognised as the discoverer of insulin.

Throughout the following decades, Banting used all platforms available to him to discredit the role of Macleod until his death following a plane crash in 1941.

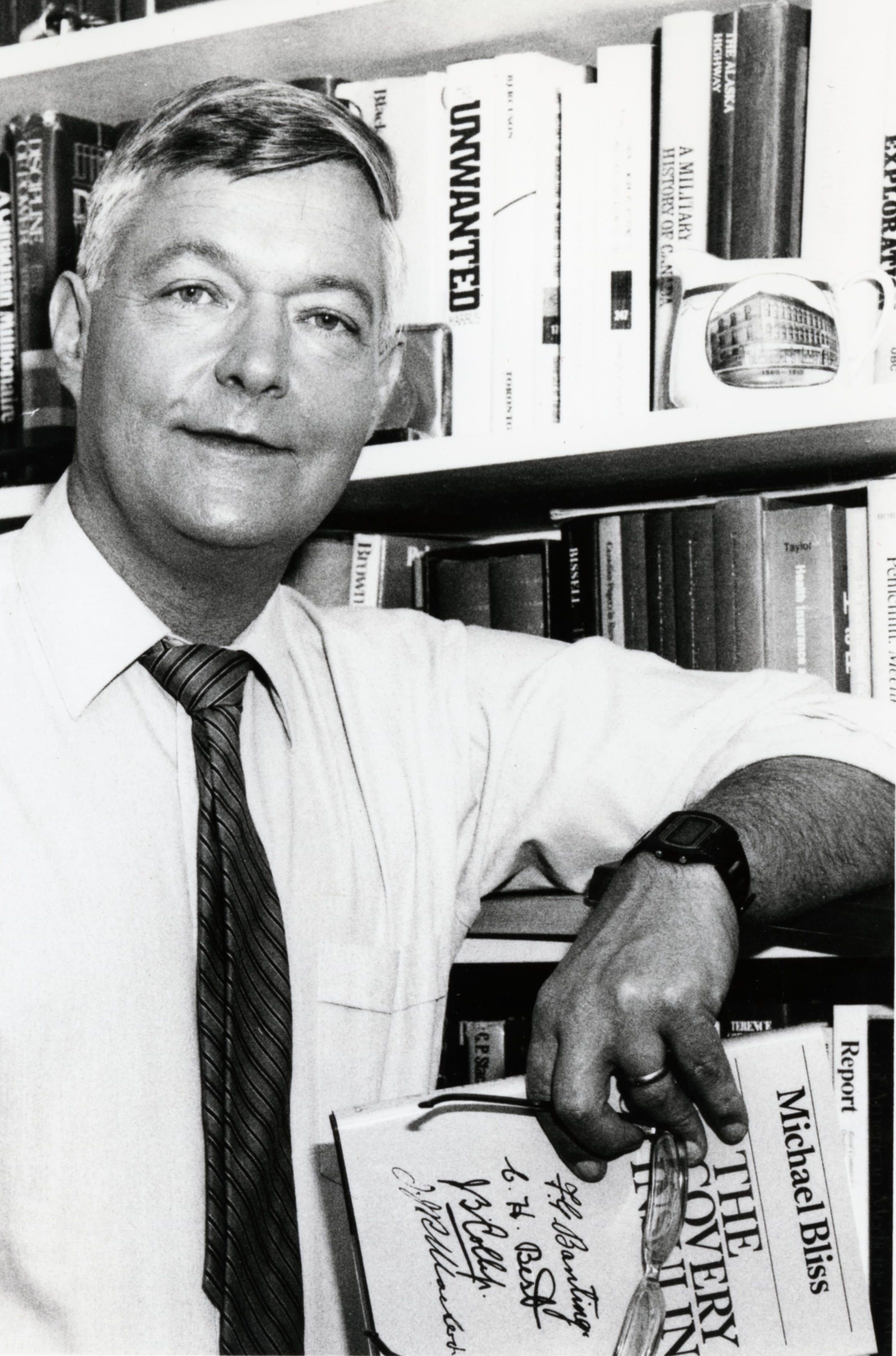

Toronto academic historian Michael Bliss, whose reinvestigation of the insulin story would later aim to restore Macleod’s place in history, wrote that this reinvention of the facts was then continued by Best.

As Bliss wrote in 2013, ‘In innumerable talks and articles about the events of 1921–22, Best systematically elevated his role in the research, reducing the contributions of Banting and Macleod, and ignoring Collip practically entirely. He portrayed JJR Macleod as a kind of caricature…who had no hesitation in taking credit for ideas and suggestions of others.’

The medals and awards, special lectureships, chairs and institutes that proliferated in the diabetes community following the breakthrough were usually named after Banting, Best or both.

By the 1950s Bliss says that Best had ‘succeeded in persuading almost everyone that he, Best, had been the key scientist on the insulin team’ – so much so that when Best’s friend, a famous UK scientist named Sir Henry Dale, wrote to him in 1961 he said ‘nobody now thinks of Macleod as having played any serious part in the discovery of insulin…all the world now thinks only of Banting and Best as the essential discoverers’.

Restoring a reputation

Michael Bliss returned to the original laboratory notes to piece together his 1982 book The Discovery of Insulin which unravelled the complex story behind the then almost universally accepted account that the breakthrough had mainly been the work of two inexperienced researchers

Drawing on contemporaneous papers and previously unknown sources, the book’s publication helped spark a broader campaign to rehabilitate the memory of Macleod, who had returned to the University of Aberdeen in 1928 as Regius Professor of Physiology, teaching and researching until he died in 1935 aged 58.

The late Professor Bliss spent over three decades promoting justice for Macleod’s memory. His last lecture in Scotland on the insulin discovery was the basis for a 2013 journal article The eclipse and rehabilitation of JJR Macleod, Scotland’s insulin laureate.

Here he wrote ‘he [Banting] never appreciated Macleod’s vital contributions throughout the research. These contributions included giving Banting and Best crucial advice on how to prepare the pancreatic extracts that proved effective, guiding their work to prevent the confused, novice researchers from going off the rails, and orchestrating successful clinical trials and elaborative physiological studies…

‘I concluded that insulin emerged at the University of Toronto as the result of a collaborative process, initiated by Banting, directed by Macleod, drawing on the great resources of the University of Toronto. This account was immediately accepted in the diabetes and scientific world …and has not been challenged in the more than 30 years that the book has been in print.’

Even in Aberdeen, the memory of Macleod had been eroded just as it has in Canada and around the world.

Dr Michael Williams, a retired Aberdeen diabetologist, revealed in an interview that he had not heard of JJR Macleod until he read of the major involvement of an Aberdeen physiologist in ‘The Discovery of Insulin’ in 1982.

This was despite Dr Williams attending the same school and university as Macleod, studying in his Physiology department only 14 years after his death, and having been a diabetes consultant in Aberdeen since 1968.

In an effort to expose this improbably well-kept secret, Dr Williams wrote several articles on Macleod’s overlooked contributions culminating in the publication of a biography entitled JJR Macleod: the Co-Discoverer of Insulin in 1993.

Bliss summed up the overturning of the myth as ‘something like redirecting an ocean liner’ but the more subtle notion of serendipitous collaboration involving Banting, Best, Collip and Macleod is still emerging 100 years later.

Prof Brian Frier, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and an internationally-recognised specialist in diabetes:

“The discovery of insulin is frequently and inaccurately attributed to Banting and Best, and for decades Macleod was effectively airbrushed out of medical history. The importance of the research of this quiet and self-effacing Scottish scientist cannot be over-estimated and he deserves to be as well-known to the public as is Sir Alexander Fleming for his discovery of penicillin”.