The Aberdeen ‘father of diabetes’ whose own life was saved thanks to the work of another University graduate

When RD Lawrence graduated from the University for the third time in 1922, he was not yet 30 and had already dedicated much of his young life to saving the lives of others.

But just a few months after being awarded his MD, he was travelling to Italy, knowing that his own death was looming and wishing to shelter his family from seeing him wither away.

The young graduate had diabetes and at the beginning of the 1920s, there was still no known cure; the only limited treatment was a painfully strict calorie controlled diet which granted patients a slightly longer life but at a huge cost as their bodies weakened and wasted.

With Lawrence’s diligent application to diet, he had already survived longer than many but now knew his time had come.

That was until a team on the other side of the world – led by another university alumnus who had sat not only in the same lecture theatres as Lawrence but in the same classrooms at Aberdeen Grammar School before that – made a remarkable breakthrough.

We explore the extraordinary parallels of the insulin story which not only saved the life of Lawrence and countless others with diabetes, but enabled him to transform support for those with the condition in ways that continue to make a difference today.

Early struggles

Robert Daniel Lawrence first came to the University of Aberdeen in 1909 as a promising former pupil of Aberdeen Grammar School.

Though he was probably unaware of it at the time his educational journey mirrored that of another Aberdeen doctor, JJR Macleod, whose pioneering work would help to save his life more than a decade later.

Lawrence excelled both intellectually and on the sports field graduating MA in 1912 having already enrolled for medicine. During his medical studies at the University, he encountered difficulties with his health requiring surgery for a burst appendix in 1914.

This left him unwell and in need of several further operations but, despite his struggles, Lawrence completed his undergraduate medical studies graduating MB ChB in 1916.

By this time many of his classmates had already gone off to war and, after a further six months of recuperation, Lawrence saw service with the Royal Army Medical Corp over the next three years, mainly in the north of the Indian sub-continent.

He returned in peace-time to work as Second House Surgeon in the Casualty Department at Kings College Hospital in London – quite an achievement for a provincial doctor from the far north.

In November 1920 Lawrence, now promoted to assistant surgeon in ENT, was practising his surgical skills in the mortuary when a splinter of bone dislodged and flew into his eye. A bad infection followed and he was admitted to his own hospital where it was incidentally found he had sugar in his urine and a diagnosis of diabetes, which likely worsened his infection, was delivered.

The diagnosis meant that the aspiring young surgeon abruptly saw his life expectancy reduced to months and, in order to extend this by as long as possible, he now had to follow a rigorous dietary regimen that would leave him weakened and constantly fatigued. Lawrence was forced to accept that his dreams of a surgical career were ended.

Nonetheless, he continued to dedicate himself to medicine turning to the less physically demanding discipline of clinical chemistry. He obtained a post in the laboratory at King’s where he studied his new specialty and conducted research writing a thesis submitted to the University of Aberdeen which led to the award of MD in March 1922.

As the summer of that year wore on, Lawrence having lived longer than many young contemporaries with diabetes was becoming more easily fatigued by work. Realising the end was approaching, he resolved to travel to Florence in Italy where he intended to live out his remaining time in a warmer climate, supplementing his army pension with private medical practice – and dying peacefully, far from the anxious gaze of friends and family.

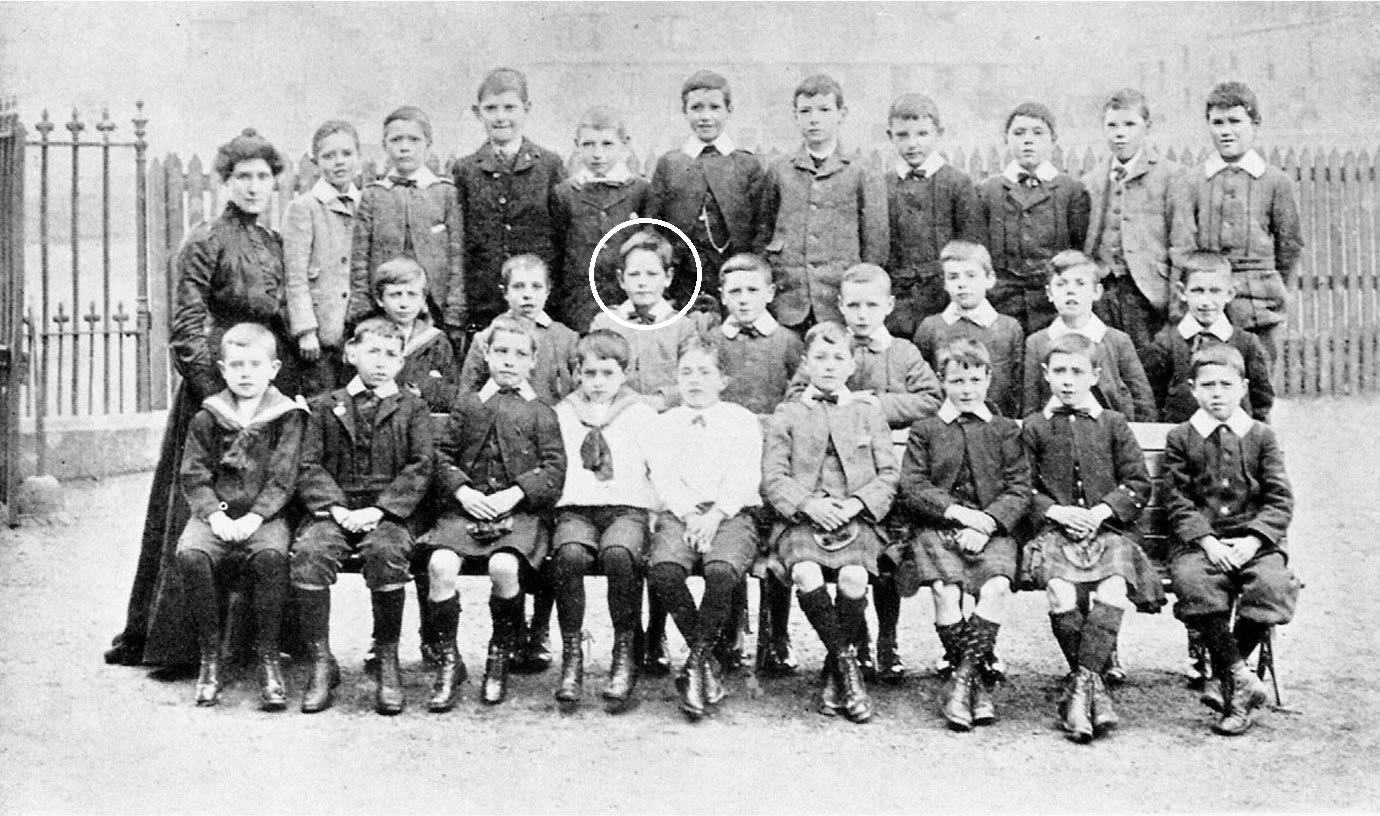

A young RD Lawrence (ringed) in Lower III at Aberdeen Grammar School 1901-2

Aberdeen Grammar School Lower III 1901-2; Lawrence tallest in middle row

Aberdeen Beach 1913; Lawrence pointing foot

Aberdeen Beach 1913; Lawrence pointing foot

An early example of leadership: Lawrence when President of the University of Aberdeen Students’ Representative Council

Lawrence as President of SRC UoA 1914; in uniform, standing in centre.

September 1921: Lawrence (circled) with colleagues at King’s when he would also have been conducting research for his MD. He can be seen getting thinner.

Lawrence (circled) with colleagues at King's in September 1921, when he would also have been conducting his MD research, can be seen getting thinner.

The life-saving telegram

While Lawrence was battling to survive and work on sparse rations, a team of Scientists in Toronto, Canada, under the leadership of another Aberdeen graduate, Professor JJR Macleod, were conducting experiments which were to have far-reaching effects.

Macleod was guiding the work of a young doctor named Frederick Banting, developing an initial idea to prepare pancreatic extracts that may be useful in treating diabetes.

Under Macleod the team, which also consisted of physiology graduate Charles Best and visiting professor of Biochemistry James Collip, was able to extract and purify what would later be named insulin.

In the second half of 1921, when Lawrence’s stringent dieting was still permitting him to make progress with his MD studies, the Toronto team were beginning to produce pancreatic extracts that showed some promise in treating experimental diabetes in dogs. Several researchers had previously reached this stage, some years earlier, but in Macleod’s laboratory that December, rapid progress was being made in producing more purified extracts that by January had shown remarkable efficacy and tolerability in human diabetes.

There were still many hurdles to overcome in demonstrating its reliability and establishing consistency in mass production. It took until April 1923 for the General Medical Council to formally approve the use of insulin as a treatment for diabetes in the UK.

By this time, Lawrence’s condition was declining fast and he was doubtless expecting the inevitable imminently when he received a telegram from former colleague Dr Geoffrey Harrison at King’s which read simply: ‘I’VE GOT SOME INSULIN COME BACK QUICK IT WORKS’.

Very weak, he hired a driver to take him on the arduous journey from Florence back to London which took 10 days to complete.

Lawrence received his first dose of insulin at King’s on May 31, 1923, and his life was saved and his professional drive restored. That, however, marked only the beginning of his diabetes journey - which would go on to have implications well beyond his own health and survival.

A healthier looking Lawrence pictured at King's in 1925

A healthier looking Lawrence pictured at King's in 1925

HG Wells: the first celebrity campaigner?

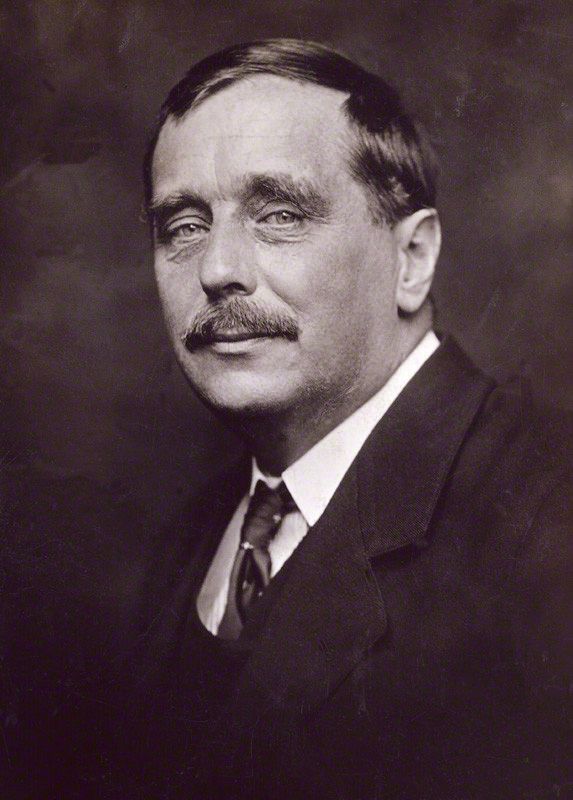

H.G Wells pictured in 1920

The diabetes campaigner with a famous patient

Having been given a last minute reprieve from an early death in 1923, Lawrence devoted his future endeavours to improving the lives of all those living with diabetes. His energetic efforts assured his place as one of the most influential diabetes specialists over the next four decades.

He conducted many experiments on the effects of insulin and its interactions with, for example, diet and exercise – often using his personal experiences, experiments and results. He also supported the establishment of specialist services for those with diabetes, running a large dedicated clinic at Kings.

He was a pioneer of patient involvement in self-care long before this became fashionable writing ‘I make no apology to doctors for writing a combined book for them and their patients …’, in the preface of his 1925 book, The Diabetic Life. This overtly inclusive work was so popular that it ran to 17 editions over the next 40 years

In the early pre-NHS years, access to insulin was only available to those who could afford it – and even then, treatment was unpleasant: once or twice daily self-injection through large, reusable needles which had to be washed and sterilised every day – as well as sharpened regularly.

Lawrence campaigned on behalf of fellow diabetic patients to make insulin and urine testing equipment available and affordable for all who needed it, and to oppose the discrimination they suffered, for example, at the hands of employers and insurance companies.

Recognising the importance of patient engagement in furthering education and welfare, as well as research, he co-founded the Diabetic Association in 1934 together with his famous patient, the science fiction writer HG Wells, author of War of the Worlds and The Time Machine.

In February 1934, Wells wrote in the Times: "It is proposed to form a diabetic association open ultimately to all diabetics, rich or poor, for mutual aid or assistance, and to promote the study, the diffusion of knowledge, and the proper treatment of diabetes in this country."

As perhaps the first celebrity campaigner, Wells had used his influence to great effect in generating interest and funds; the Diabetic Association was up and running by March and Wells was elected its first President.

The model established was replicated around the world and in due course the association was renamed the British Diabetic Association or BDA (known as Diabetes UK since 2001).

Lawrence was Chairman of the Executive Council from 1934–1961 and became Honorary Life President in 1962. His enthusiasm and drive ensured the life and steady growth of this association, which soon became the voice of people with diabetes. Today there are more than 400 DUK local voluntary groups across the country, run by patients for patients.

He was also heavily involved in the establishment of the International Diabetes Federation and was elected its first president in 1950, a position he held with distinction until 1958, after which he was appointed Honorary President.

Lawrence suffered a major stroke in late 1957 and despite residual left-sided weakness he was able to resume clinical practice for a time and remained active at meetings and conferences for several years. His final publication on diabetes, once more describing his own symptoms, was in the Lancet in June 1967 only 14 months before he died just short of his 76th birthday. The life-saving interjection of insulin had afforded him an extra 45 extraordinarily productive years.

A lasting legacy

Lawrence’s name continues to live on in diabetes practice. Patients who have lived 60 years with the condition are entitled to receive the Lawrence Medal, named in his honour and presented by Diabetes UK. The same organisation also has an RD Lawrence lecture at its annual scientific conference and awards RD Lawrence fellowships to support young researchers.

The legacy of his work lives on around the world and at the University of Aberdeen; the first research grant awarded by Diabetes UK (then the Diabetic Association) went to a young Dr Hans Kosterlitz in 1935, two years after he had joined Professor JJR Macleod’s Physiology Department at Marischal College. Kosterlitz would go on to secure his own place in scientific history for his work on endorphins.

University Principal, Professor George Boyne, says a huge debt is owed to both Lawrence and his fellow Aberdeen graduate JJR Macleod.

Diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in his teens, as well as an alumnus of both Aberdeen Grammar School and the University, their work has saved and transformed his own life and that of millions of others across the world.

“In this year that the world marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, it is fitting that we look back on the achievements of these two great scientists, who both undertook their training at the University of Aberdeen,” he adds.

“A century may have passed since the discovery of insulin in Macleod’s laboratory but, as I know only too well, the legacy of his team’s work continues to be felt today.

“Insulin has saved countless lives across the world and the support received by those living with diabetes continues to be influenced by the work of RD Lawrence and the important charities he created.”

* With thanks to the Lawrence family archive for photographs supplied. Further details of Lawrence's remarkable life can be found in 'Diabetes, Insulin and the Life of RD Lawrence' by Jane Lawrence (edited by Robert Tattersall) (2012; Royal Society of Medicine Press; ISBN 978-1-85315-969-5).