Shedding new light on Scotland’s mysterious Picts

Despite their iconic status, the archaeology of the Picts has remained elusive.

Work led by the University of Aberdeen has transformed understanding of this period, enhanced interest around the world, engaged communities and supported national heritage objectives.

The Picts have long been regarded as a mysterious people, leaving behind little evidence of their presence other than their iconic carved stones.

Their image in popular culture is of a wild warrior tribe of painted people.

But work by University of Aberdeen archaeologists is revealing a very different picture of the early societies of northern Britain given the name 'Picti' meaning 'Painted Ones', by the Romans.

Their excavations have shown the Picts to have been a much more sophisticated society, in touch with trading networks that extended across Europe and creating large, hierarchical settlements.

A series of archaeological discoveries led by Professor Gordon Noble has added a significant body of evidence which points to a much more complex Pictish society and work by the team has put the Picts on an international stage, both through wider public engagement and by increasing collective knowledge to open a gateway to their world.

Pictish kingdoms

Fundamental to the creation of the medieval kingdom of Scotland was the establishment of the Pictish kingdoms of eastern and northern Scotland, contemporary with Anglo-Saxons further south.

First mentioned in late Roman writings as a collection of troublesome social groupings north of the Roman frontier, the Picts went on to dominate northern and eastern Scotland until late first millennium AD.

They left behind major legacies, including some of the most spectacular archaeological sites and artistic achievements of early medieval European society.

But all trace of the Picts disappeared from the written records in the 9th century AD, and only limited and contentious documentary sources survive to evidence their six centuries of life.

It is recognised that archaeology is key to exploring this period but the archaeology has been traditionally difficult to identify with only a handful of settlements known.

Since 2012, Professor Noble has led the University of Aberdeen ‘Northern Picts project’ and the sister project ‘Comparative Kingship’ project, made possible by grants totalling £2 million from a variety of bodies.

A series of excavations has revealed settlements of unprecedented size and scope and led to the discovery of a huge new body of information on Pictish society.

In 2021 work led by Aberdeen on the Picts won the prestigious Current Archaeology magazine Research Project of the Year.

Key discoveries

‘Royal’ Rhynie

In 2011 the Northern Picts project began work at Rhynie in Aberdeenshire. In the 1970s the iconic Rhynie man, a six-foot high Pictish stone carved with a distinctive figure carrying an axe, was uncovered by a farmer ploughing a field and a Pictish symbol stone known as the Craw stane still stands.

Despite this, little was known of the nature of the site and how or why it was used by the Picts.

Excavations revealed exceptionally rare evidence for Mediterranean and Continental imports that showed for the first time that the Picts were important participants in developing international networks – networks that included contacts with the Byzantine Empire and Merovingian France and the Kingdoms of western Britain and Ireland. Among the intricate metalwork uncovered was an axe-shaped pin with a serpent design that resembles the axe carried by the Rhynie Man

The work at Rhynie indicates it was a high status – and possibly an early medieval royal centre - that pre-dates any identified in Britain previously.

Ongoing work at Rhynie aims to uncover more of the royal complex and to improve understanding of settlement, burial, cult and ceremony – key components of an early royal pagan centre of Pictland.

The northernmost pre-Viking Age silver hoard in Europe

In 2013, the Aberdeen team, along with the National Museum of Scotland, returned to a farm in Aberdeenshire where almost 200 years earlier labourers had cleared a field with dynamite.

The 1800s land clearance led to the discovery of three magnificent sliver artefacts, a chain, a spiral bangle, and a hand pin. However, the workers didn't search any deeper to check if there were any more treasures and the field was turned into farmland.

The detailed excavations of the archaeology team yielded more than 100 new objects, known as the Gaulcross hoard, including objects never identified before.

This provided insights into the access of native groups to late Roman silver and the trade and exchange of recycled Roman silver in the post-Roman period.

The finds included fragments of sheet silver, hacked dish fragments, pendants, spoon handles, strap-end/belt fittings, silver ingots and fragments of late Roman clipped siliquae.

Only one other Pictish silver hoard of this size and scale is known and this was found in the 19th century.

Pictish power centres at Dunnicaer and Burghead

Since 2015 The Northern Picts project has been working at an inhospitable sea stack south of Stonehaven known as Dunnicaer and at a known Pictish fort in Burghead in Moray.

With the help of experienced mountaineers, the archaeologists scaled the Dunnicaer rocky outcrop, which measures at most 20 by 12 metres and is surrounded by sheer drops on all side.

They uncovered evidence of ramparts, floors and a hearth and carbon dating revealed it to be the earliest yet-discovered Pictish Fort, in use in the 3rd or 4th century and pre-dating its more famous neighbour Dunnottar Castle.

At Burghead, although the Pictish connections were known, it had been assumed that the majority of archaeology had been destroyed with the building of the new town, with the seaward defences destroyed and used to build the harbour.

But a series of ongoing digs are revealing that the fort’s large ramparts have survived far better than anyone had anticipated, despite their wilful destruction over the centuries.

Evidence of numerous buildings also show it was a densely populated and important Pictish site and metalwork, weaponry, hair and dress pins point to a complex settlement spanning the years 500AD to 1000AD.

Excavations at Dunnicaer and Burghead have more than doubled the number of early medieval buildings known from lowland Scotland.

The team has also collaborated with the University of Dundee to produce a series of spectacular reconstructions, offering the public an opportunity to see how Pictish life may have looked more than 1000 years ago.

An urban-like centre - Tap O’ Noth

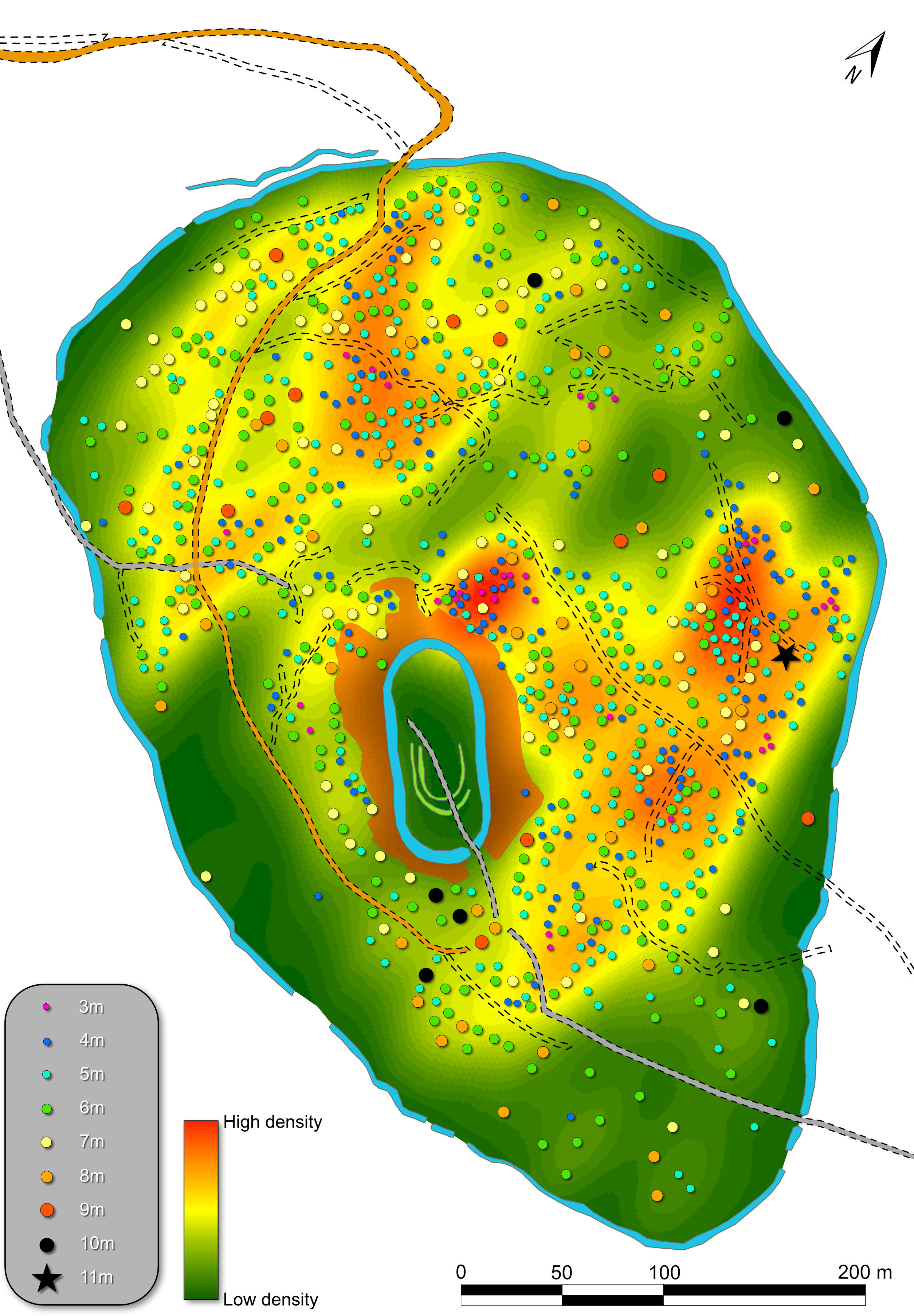

At Tap O’ Noth, an imposing hill which rises above the village of Rhynie, the Aberdeen team made their most spectacular find yet.

Using radiocarbon dating and aerial photography, archaeologists uncovered evidence which indicates that as many as 4,000 people may have lived in more than 800 huts perched close to the summit.

Their discovery means that the area, which today is a quiet village home to just a few hundred people, once had a hilltop settlement that at its height may have rivalled the largest known post-Roman settlements in Britain and Ireland.

The Tap O’ Noth discovery shakes the narrative of this whole time period. If each of the houses we identified had four or five people living in them then that means there was a population of upwards of 4,000 people living on the hill.

That’s verging on urban in scale and in a Pictish context we have nothing else that compares to this. We had previously assumed that you would need to get to around the 12th century in Scotland before settlements started to reach this size.

It is truly mind blowing and demonstrates just how much we still have to learn about settlement around the time that the early kingdoms of Pictland were being consolidated.

Rewriting the history of the iconic Pictish symbols

The meaning of Pictish symbols has been debated for over a century. Through the excavations at key Pictish sites such as Dunnicaer, Rhynie, and through direct dating of artefacts in museum archives, the project team has shown that the origins of this system are earlier than previously countenanced.

Dating work placed the development of the symbol system in the third-fourth centuries AD – an earlier period than many scholars had assumed.

The symbols may have been a naming system communicating the identities of Picts and it is likely that this was developed in the same era as other forms of writing and communication across Europe like the ogham script of early Ireland and the runic system developed in Scandinavia.

The team has developed a ‘new and more robust’ chronology which identifies a clear pattern in both the likely date and the style of the carvings.

"Examining associated dates from archaeological excavation is helping us rewrite the history of these symbolic traditions of Northern Europe and to understand more clearly the context of their development and use".

Impacts

- Enhancing interest in - and creating public understanding of Pictish culture with audiences around the world. Through documentaries, numerous media contributions and an active social media presence the team’s work has transformed understanding of the Picts.

- In an online survey of 300 people, 95% of those asked stated that the project had influenced their interest or understanding in the Picts, with respondents saying that it had ‘opened up a new world’, ‘breathed life into the Picts’, that they had a ‘much more-fact-based understanding’.

- Engaging communities in their local history and heritage – local participants have been part of excavation teams and since 2013, 200 people have learned new skills by joining digs. The project team also worked with local school and community groups, stimulating conversations and informing a sense of place.

- Supporting the delivery of national heritage objectives - the Head of Archaeology and World Heritage at Historic Environment Scotland (HES) described the project as having ‘a transformative effect on the understanding of the Picts and their role in Scottish and wider European society’.

- Stimulating cultural tourism - The discovery of the Gaulcross silver hoard inspired and underpinned a new exhibition by National Museums Scotland, seen by 68,000 people in Edinburgh and as part of a touring display. Work with smaller regional museums, including the Tarbet Discovery Centre, has also boosted visitor numbers. A video produced on the work at Rhynie and shared by National Geographic has been viewed more than a million times.

- Inspiring creative practice – an arts collective know as Rhynie Woman was inspired by the excavations to find creative ways to engage the public including through a pop-up museum, café and walking trails. The Tap o’ Noth findings inspired a light festival, ceilidhs and new musical compositions.