Remembering MRI pioneer, Professor John Mallard

"Persevere in your endeavours, to the end-success or failure"

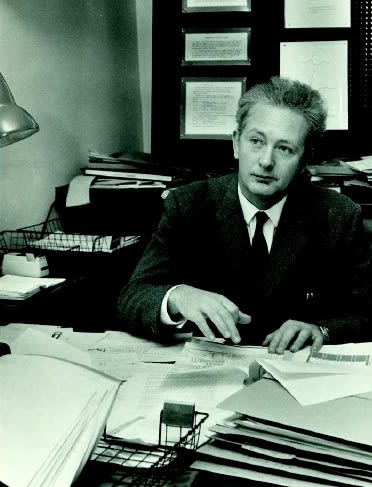

Professor John Rowland Mallard became an honorary son of Aberdeen when, in 1965, he was appointed as the first professor of Medical Physics at the University of Aberdeen, becoming the first holder of the Chair in this subject in Scotland.

The move marked a homecoming for his wife, Fiona, who was born and raised in the City, and the start of a new chapter for Professor Mallard – one which would change the course of medical history forever.

John Rowland Mallard was born in Northampton in 1927, where he grew up above his parent’s grocer shop. He would joke that his early experience using the bacon slicing machine influenced his ideas on images produced by body scanners.

One of his most outstanding characteristics was his courage to overcome adversity. Profoundly deaf since childhood and with no hearing aids when he was young, he learned to lip read and to enunciate each word clearly. He was always grateful for the support he received from family and teachers. He won a scholarship to Northampton Town and County School and then studied physics at the University of Nottingham. He completed a PhD on the magnetic properties of Uranium in 1951 which resulted in the distinction of achieving an entry into the Kaye and Laby scientific reference textbook.

John then began working in what was at the time called hospital physics, investigating nuclear medicine technology and its clinical applications. After two years at the Liverpool Radium Institute, he moved in 1953 to Hammersmith Hospital to take up the post of senior physicist in the Royal Postgraduate Medical School of the University of London. He became Head of Department in 1957 and Reader in 1963, before moving to St Thomas’s Medical School as Reader in 1964. In London, he built the first whole body radio-isotope scanner in 1957, now on display at the London Science Museum, and also built the first gamma camera in the UK.

It was at Hammersmith hospital that he met his beloved wife, Fiona Lawrance, who was far from home and working as a medical secretary. They were married in Rubislaw Church in Aberdeen in 1958 and their two children, John and Katriona, were born at Hammersmith Hospital.

Through his early work, he had discovered that tumours and normal tissues have different magnetic resonance signals. This was published in Nature in 1964, to little notice. However, this became the driving force of his idea of the usefulness of building a whole-body scanner to detect these differences and this was what he took to his new post in Aberdeen.

After a long battle to convince funders of the value of his idea, his team developed the Mark -1 MRI scanner on a shoestring budget. They overcame considerable technical hurdles to produce the first ever clinically useful full body MRI scanner. He used his tenacity to push through his research with his team becoming their own “guinea pigs” to demonstrate the benefits of the equipment, scanning each other until in 1980 they were ready for their first patient. On 26 August 1980, they captured the first ever diagnostically useful images on a volunteer with terminal cancer which showed up known cancer deposits as well as additional tumours in his spine.

The Mark I MRI scanner, which is now on display in the Suttie Art Space at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, was used to scan more than 9,000 patients over the next decade. The second imager built by the team was dedicated to clinical work.

Today, MRI machines are a routine part of medical treatment in specialties from psychiatry and cardiology to orthopaedics and oncology, allowing clinicians to look inside the human body in amazing clarity and detail.

When the Aberdeen scanner demonstrated the first ever images of multiple sclerosis, it was of great personal significance to Professor Mallard as he wished to help his dear cousin who suffered from the disease. He said: “It is my fervent hope that these techniques will help to put a big nail in the coffin of the cancer story and play a major part in the onslaught of brain and mental disorders and ageing.”

Professor Mallard continued to champion other advances in imaging technology. In his Inaugural lecture at Aberdeen University, he predicted that PET (Positron Emission Tomography) would become one of the most powerful tools for studying human disease. Scotland’s first PET Facility was created at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, now named the John Mallard Scottish PET Centre.

Also in his Inaugural lecture at Aberdeen University, Professor Mallard noted that acquisition of a nuclear particle accelerator, known as a cyclotron, would be extremely valuable for Scottish medicine. He and Fiona deeply appreciated the tremendous local public support shown to their fundraising campaign which helped to make this happen.

Professor Mallard believed strongly in the importance of teaching. He made Aberdeen a leading centre for training physical scientists to work in medicine through one of the first MSc courses in the world to cover the whole field and supporting numerous relevant PhD projects.

Through his fierce loyalty to his profession, he contributed significantly to the worldwide place of the physical sciences in medicine at the highest levels and he founded collaborative organisations, and their international counterparts.

He believed in collaboration between all fields within the University and the Hospital to achieve the goal of improving healthcare. He had a determined spirit backed with tenacity and intuition, however, was unassuming with a gentle kindness that would come to the surface when most needed. His drive applied to all around him, but most of all, to himself.

Professor Mallard was held in high esteem by colleagues around the world. He donated the many medals and awards he received over his career, including his OBE, to the Aberdeen Medico-Chirurgical Society. These are on display at the Suttie Centre at the Aberdeen Medical School. At the time, Professor Mallard explained: “My wife Fiona and I hope that the medals will serve as a permanent reminder of the terrific stir and excitement which the work here caused at the time, in the scientific and medical world.” Exhibited close by in the Suttie atrium is the artwork by sculptor Marilène Oliver, “Doctor-Patient”, which incorporates MRI scans of both Professor Mallard and Mr Ian Suttie reflecting on the connections uniting healthcare professionals and patients.

After retirement in 1992, he and Fiona were thrilled and deeply moved when, in 2004, Aberdeen bestowed on him the highest honour of the Freedom of the City. This was indeed a very happy day which was shared with all the family, colleagues and friends. Scottish singer and songwriter Fiona Kennedy performed at the event to his great delight and will do so again today.

Professor Mallard was also very proud to be recognised as part of the history of the Borough of Northampton when he was made a Freeman at Northampton Guildhall in 2018. He said at the time: “My work would not have been possible without the wonderful support of Northampton in my early years. With Northampton Borough Education Department funding me, I was one of the very few who were able to go to University, for which I am very grateful indeed.”

John was a deeply loved father and grandfather. Always encouraging and supportive, with a gentle laugh and sense of humour. Always showing concern and interest and a deep depth of humanity and caring.

He and Fiona were married for 62 happy years until Fiona’s death in 2020. Professor Mallard passed away on February 25, 2021. Both funerals were held in Rubislaw Church, Aberdeen where they had been married.

Emeritus Professor Peter Sharp, who worked for Professor Mallard and then became his successor, describes his lasting legacy: “John Mallard was one of those scientists blessed with a vision, a vision of what physics could contribute to healthcare. Many millions of patients worldwide have good reason to be grateful to him.”

Persevere in your endeavours, to the end-success or failure. Ignore those- even those powerful people-who say ‘it won’t work’ and there will always be plenty of those