‘To aim for the highest point is not the only way to climb a mountain’

The life and work of University graduate Nan Shepherd

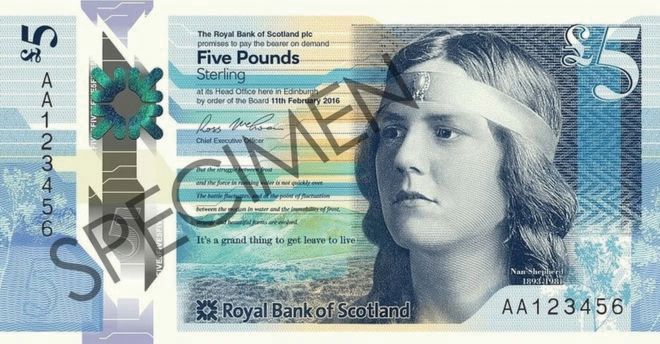

Nan Shepherd was one of the University’s first female graduates and her face can be seen on Royal Bank of Scotland five-pound notes.

Her much-celebrated work The Living Mountain was described by the Guardian as ‘the finest book ever written on nature and landscape in Britain’ but it spent more than three decades gathering dust in a drawer before it was finally published.

Shepherd’s vivid descriptions and observations about the Cairngorms have in recent years earned her a place among the literary greats but in life she was notoriously modest. Though many of her early works attracted critical acclaim and readers around the world, she remained as committed to teaching as to her own literary endeavours.

We look back on her achievements as a celebrated writer of prose and poetry, an editor, inspiring lecturer and traveller who loved literature and landscape.

Nan Shepherd

Nan Shepherd

A home which inspired a love of the hills

Nan (Anna) Shepherd was born at Westerton Cottage in East Peterculter in 1893 and brought up in Cults, Deeside, three miles west of Aberdeen.

The daughter of John Shepherd, an engineer, and Jane Kelly, she attended Cults School and Aberdeen High School for Girls.

A month after her birth, the family moved to the house where Shepherd would live for most of her life: Dunvegan, 503 North Deeside Road, Cults. It had a garden overlooking the hills and her early life cemented the love of nature and landscape which inspired her literary work.

After completing her schooling, Shepherd was accepted to study at the University of Aberdeen in the first decades after women were allowed to do so.

University life

Shepherd attended the University of Aberdeen from 1912 to 1915, graduating in 1915 with an MA. Her last year at university coincided with the start of the Great War.

She achieved notable academic success, gaining high marks and winning several prizes, and was interested in both the writers of the past that she encountered during her degree and the writers who were emerging in Scotland.

In October 1913 she joined the committee of Alma Mater, an ambitious weekly student publication which had started in 1883.

Shepherd was influential in its output throughout the war continuing as a contributor, editor, and administrator until well after her own graduation in 1915. She also edited the Aberdeen University Review.

It was Alma Mater where she published her earliest work and when she retired as editor, in 1917, it was far from the end of her association with the magazine.

Alma Mater remained the primary recipient of Shepherd’s poetry, and the magazine published more than 20 of Shepherd’s poems along with several unsigned prose pieces. Many of these contained Doric and Shepherd was an early advocate of the use of Scots.

In 1922, Shepherd was persuaded by the then editor, Eric Linklater, to contribute to an annual Alma Mater Special Hospitals Issue, along with several well-known national and local writers, in order to raise funds for Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and the Sick Children’s Hospital. Between 1922 and 1934 Shepherd donated eight short, signed prose pieces to the publication.

Shepherd attended the University during a very exciting time for English Literature. Among her professors was Herbert Grierson, who was developing the discipline at Aberdeen and she studied alongside other significant female writers including Agnes Mure Mackenzie, Rachel Annand Taylor and Flora Garry.

But this period was also interrupted by war and by the time she graduated many of the men had gone off to fight. At the ceremony to confer her degree the names of the fallen were read out and included more than 20 of Nan’s Arts Class of 1912. This experience features in her writing for the Aberdeen University Review.

Professor Ali Lumsden, Regius Chair of English Literature at the University of Aberdeen, says: “It is clear that her University experiences shaped her as a person and as an author and her first published novel The Quarry Wood features a central female character who comes to study at the University of Aberdeen in the early years of the twentieth century.”

Following her graduation Shepherd taught English at Aberdeen Training Centre for Teachers until her retirement, maintaining her University connections and giving enthralling literature lectures until she was well into her eighties - always without notes.

The University awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1964.

A creative burst

Although Shepherd lived for almost ninety years, her main published work appeared over just six years in an intense burst of activity comprising three novels, The Quarry Wood (1928), The Weatherhouse (1930), A Pass in the Grampians (1933) and a single poetry volume, In the Cairngorms (1934).

All were published while she was working as a lecturer in English at Aberdeen Training Centre for Teachers and her literary output was often associated with holiday periods.

Shepherd – a keen hillwalker – took every opportunity to escape into her beloved Cairngorm mountains which provided the inspiration and backdrop for much of her writing after she had first set foot on their ice-cold peaks in 1928. She would regularly hike for days, often camping out on the mountain.

The harsh north-east landscape provided the background to her first three books, each tackling in different ways the insular country communities, looking at women torn between family and the exciting new opportunities offered by the modern age.

Shepherd’s first novel, The Quarry Wood, which she began writing in 1922, was rejected by thirteen publishers before finally appearing in print six years later but was greeted with immediate critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic.

Professor Lumsden stresses that although Shepherd’s work had the north-east at its heart, it was far from parochial.

“She may have lived most of her life in the same house and lived and worked in the north-east all of her life but she was very well travelled and in correspondence with writers all over the world.

“Shepherd used the regional to explore concerns that are relevant far beyond the north-east and that is why her work was as well received in the US as it was in Scotland. Her writing deals with the complexities of women’s experience in the early years of the twentieth century, and in particular the tensions that potentially exist between education and the domestic sphere.

“But she never wrote for the plaudits. Shepherd once said that she only produced creative work when she had something worth saying. She very much wanted to feel she was doing something valuable and the work she did training teachers was equally as valuable as her writing – inspiring generations to promote literacy and writing.”

Rediscovered after three decades

Shepherd had much more to say by the 1940s as her love affair with the Cairgorms continued. Although she had scaled its highest peaks, it was not the achievement of reaching the top which held the greatest appeal. Instead she was fascinated by what happened to mind and matter on the mountain’s slopes.

Shepherd wrote to a friend in 1940: “To apprehend things – walking on a hill, seeing the light change, the mist, the dark, being aware, using the whole of one’s body to instruct the spirit… it dissolves one’s being. I am no longer myself but part of a life beyond myself.”

Her thoughts and observations on the Cairngorms began to come together under the title of what is now her most famous work, The Living Mountain, sometime in the final years of the Second World War.

A masterpiece of observation and contemplation she used her intimate knowledge of the mountain to transport the reader to the beautiful, remote and rugged landscape.

Shepherd sent her manuscript, completed in summer 1945, to a novelist friend called Neil Gunn. He responded with praise but suggested that it might be hard to get published without photographs and a map.

She sent it to just one publisher and his prediction proved right as it was rejected. Shepherd then put her manuscript away in a drawer where it would remain for more than 30 years before reaching a wider audience.

Professor Lumsden explains: “The Living Mountain was ahead of its time in its innovative approach to our relationship with landscape but as a result it didn’t fit easily into the genres of 1940s publishers.

“‘Shepherd accepted that her work would not be published - and Gunn remained its sole reader for many decades - but she was not necessarily heartbroken by this.

“She writes through the lens of contemplation and The Living Mountain was penned primarily as a journey of self-discovery reflecting her love of nature, rather than to enhance her already considerable literary success.”

It was only as Shepherd reached the final years of her life that she retrieved the manuscript from the drawer convinced it was still valid.

Her connections with the University finally brought it to greater attention when it was accepted and published by Aberdeen University Press in 1977.

A lasting legacy

As Shepherd notes in her preface to The Living Mountain, a 30 year wait in the lifetime of a mountain is just ‘the flicker of an eyelid’.

It has retained its relevance to modern readers despite almost 80 years passing since she first put pen to paper to describe the experiences captured in The Living Mountain.

Shepherd’s contribution to literature has now been recognised with her own stone in Edinburgh’s Makars’ Court, bearing the words from The Quarry Wood ‘It’s a grand thing to get leave to live’ and in 2016 her significance was acknowledged in the decision to place her on the Royal Bank of Scotland five-pound note as part of a 'Fabric of Nature' series.

Professor Lumsden says: “Shepherd’s understanding of the connectedness of human beings to the natural world has made The Living Mountain a much-loved work.

“Since its more recent republication many new audiences have engaged with her writing from ecological perspectives as we become increasingly aware of the fragile nature of our planet.

“It is fitting that she should now be considered among our literary greats. She was certainly an active member of the international community of literature, corresponding with many other writers throughout her long lifetime, even if her own outputs were limited to just a few periods.

“Shepherd’s writing will be enjoyed for decades to come but perhaps her greatest legacy is not found in her own pages but in the generations of young writers she both inspired and supported and in the generations of teachers she imbued with her passion for literature and learning.”