Honouring the ‘Toronto Four’

More than a century on from the awarding of a Nobel prize for the discovery of clinically useful insulin, a series of events were held in Aberdeen to honour the ‘Toronto four’, credited with the lifesaving breakthrough.

The celebrations mark the first time the four have been commemorated together and reflect changing attitudes and a reassessment of the contributions of each man to the advance in science which has saved the lives of millions of people with Type 1 diabetes.

For University of Aberdeen graduate and later Regius Chair in Physiology, JJR Macleod, the events also signified further restoration of his reputation and rightful place in the history books.

How a major breakthrough turned sour

Celebrating the involvement of four people involved in one of the greatest medical breakthroughs of all time may not be seen as controversial. Convention dictates that each should have their contribution recognised and their achievements recorded.

But for decades the names of Banting, Best, Collip and Macleod have rarely been put together in a sentence which did not end with negative associations.

To understand the significance of the Aberdeen joint celebration, it is necessary to return to the story of insulin discovery and the myths which have grown up around it.

From the first successful injection January 1922 – even the date is subject to argument – until the 1980s, most popular accounts credited the discovery of insulin to two inexperienced Canadian researchers, Frederick Banting and Charles Best.

Their names became entwined with the success story while that of Macleod, an internationally recognised expert on carbohydrate metabolism for more than a decade who managed the laboratory in which they worked, was tarnished with accusations that he took credit for discoveries where it was not owed.

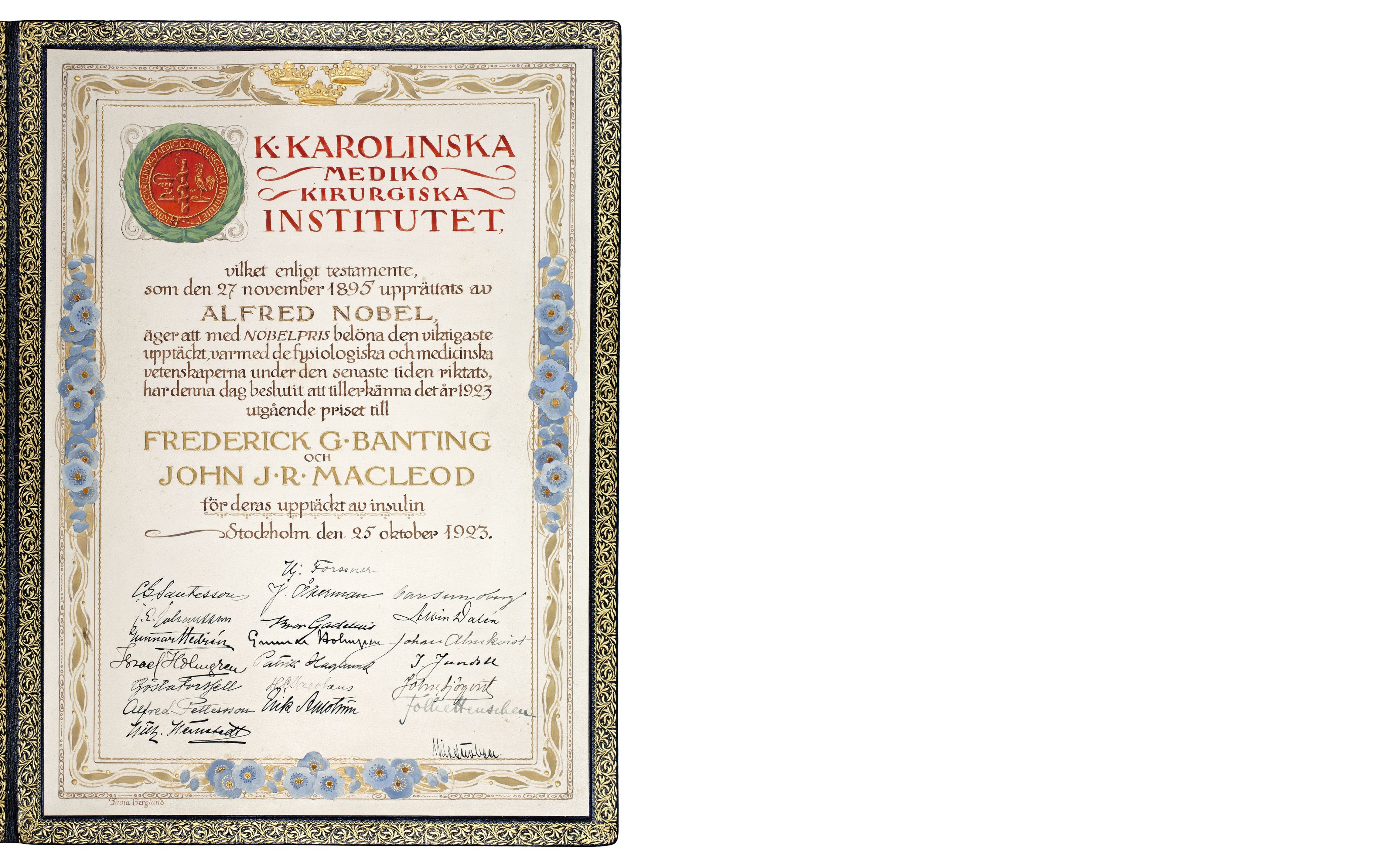

The awarding of the 1923 Nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine jointly to Macleod and Banting triggered an academic war of words which has dogged the lifesaving intervention for a century.

From a shared prize to a seismic split

Both Macleod and Banting split their Nobel Prize winnings with their co-workers – Macleod giving half to James Bertram Collip, a biochemist who used his considerable laboratory expertise to purify the extracts, while Banting shared his with his assistant Charles Best , a summer student who had learned glucose measurement skills in Macleod’s practical classes.

The division into the two camps immediately intensified. Banting was quick to share his anger - and his views that Macleod’s share was ill deserved -- with his friends and one, his former teacher Dr William Ross, organised a successful campaign in Canada to have Banting recognised as the discoverer of insulin.

Throughout the following decades, until his death after a plane crash in 1941, Banting used all platforms available to him to discredit the role of Macleod. This narrative was then continued by Best and the medals and awards, special lectureships, chairs and institutes that proliferated in the diabetes community following the breakthrough were usually named after Banting, Best or both.

By the 1950s a famous UK scientist named Sir Henry Dale, a friend of Best, wrote that ‘nobody now thinks of Macleod as having played any serious part in the discovery of insulin…all the world now thinks only of Banting and Best as the essential discoverers’.

A shift in this attitude did not come about until Canadian historian Michael Bliss published a reinvestigation of the story in his 1982 book The Discovery of Insulin. After revisiting original laboratory notes and other sources he concluded that ‘insulin emerged at the University of Toronto as the result of a collaborative process, initiated by Banting, directed by Macleod, drawing on the great resources of the University of Toronto’.

Bringing the ‘Toronto Four’ back together

Although divisions between Banting, Best, Collip and Macleod may not have healed in their lifetimes, a century on key figures from the diabetes world gathered in Aberdeen to celebrate what they achieved together.

Macleod, a medical graduate from the University of Aberdeen, returned as Regius Professor of Physiology in 1928, a position he held until his death in 1935.

An afternoon symposium with speakers from Canada, Sweden and Scotland was held on September 6 – Macleod’s birthday – following a morning Dedication Ceremony where four bronze plates with the names of the four team members were unveiled.

The addition of the Toronto Four plaques around Macleod’s statue in Aberdeen’s Duthie Park transformed the memorial - the result of a fundraising campaign by former University student Kimberlie Hamilton and her -partner John Otto - into the world’s only monument honouring the entire history-making team

Among the speakers at the symposium was Professor Erling Norrby, a virologist and former member of the Nobel committee who has written a series of books on the history and consequences of Nobel prizes in science and medicine. He says his views and insights ‘have been strongly modified and amplified’ by recent meetings and events focused on the insulin discovery and concluded that from ‘relatively limited information available at the time the Nobel committee in 1923 happened to make the right choice’.

Professor John Dirks a former Dean of Medicine at the University of Toronto and later President and Scientific Director of the Canada Gairdner International Awards involved in the adjudication and awarding of the worlds’ best medical scientists, also presented at the Aberdeen event, representing the Toronto Medical Historical Club.

He described the discovery of insulin as ‘the highest standard of achievement in medical science with huge clinical benefit to millions of people with diabetes’.

“Unfortunately, the initial credit quickly went to Banting and Best, as Banting was involved in the miraculous clinical treatment of dying diabetics, and Best, his lab colleague, in the rapid commercialization of insulin. They remained in Toronto and became national heroes in Canada for almost the next century,” he says.

“It took medical historian Michael Bliss of the University of Toronto to correct this misinformation with his brilliantly researched book, The Discovery of Insulin, which revealed exactly who did what back in 1921 and 1922. The publication of this book began to unassailably restore the significant roles played by John Macleod and Bertram Collip. This has been amplified by further research that has continued up until the present time.

“There is no doubt that without Macleod in Toronto in the 1920s nothing would have happened. Macleod and Banting truly deserved the Nobel Prize and Collip’s role was also critical to the Toronto team’s success.”

Professor Dirks described bringing the four co-discovers together in a memorial as ‘a historic event of extraordinary significance, an occasion when the historical record is publicly set right like never before, via an outstanding symposium by the most knowledgeable historians and a former representative of the Nobel Prize committee in Stockholm’.

“I believe that many more people will come to recognize that the discovery of insulin – a hugely important medical breakthrough that has benefitted millions of people worldwide – came about thanks to four great scientists in Toronto, which good fortune brought together in the right place at the right time!” he concluded.

The name plaques of the Toronto Four at the Macleod memorial

The name plaques of the Toronto Four at the Macleod memorial

Other speakers at the events included:

· Peter Kopplin, a retired Toronto Physician and Secretary of the Toronto Medical Historical Club (TMHC) who spoke at the symposium on the TMHC which is currently in its centenary year.

· Alison Li, Toronto historian and a former PhD student of Michael Bliss, who presented on Collip. She is the author of ‘J.B.Collip and the Development of Medical research in Canada’ (2003).

· Chris Rutty, Toronto historian and a former PhD student of Michael Bliss, who has been involved in many presentations concerned with the insulin centenary celebrations. He spoke on Best.

· James Wright, a Calgary based retired pathologist and accomplished medical historian, particularly in the area of Macleod’s fish insulin research, which he spoke on in Aberdeen 21 years ago. He spoke on Banting at the Toronto Four symposium.

· Ken McHardy, a retired Aberdeen diabetologist and Honorary Senior Lecturer at the University of Aberdeen who spoke on Macleod’s contributions.