6. Fairy Tales and Children's Literature

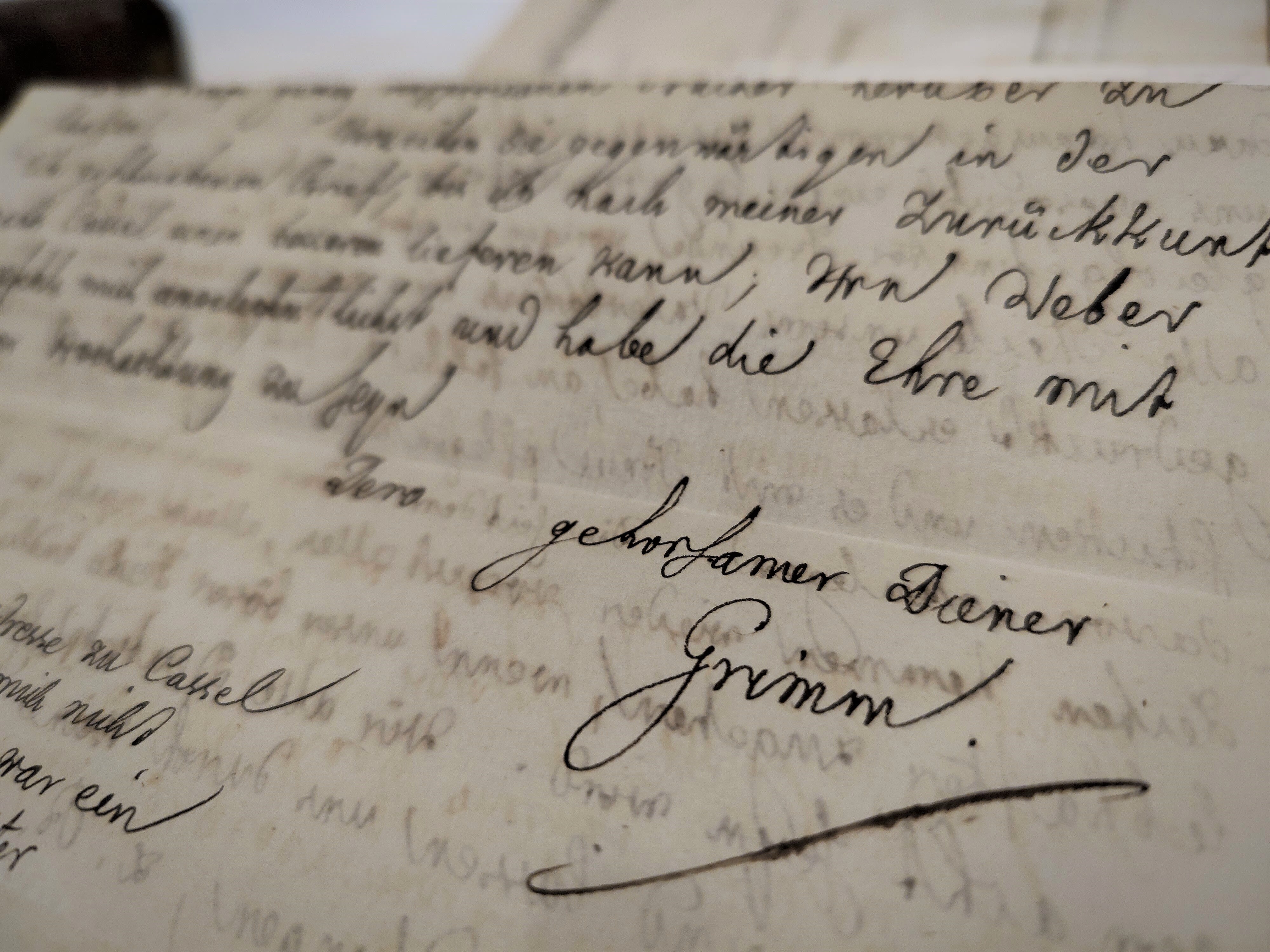

Whilst Scott was collecting his chapbooks, and indeed ballads and songs, the Brothers Grimm and other like-minded individuals were similarly compelled to collect the traditional fairy and folktales of Europe. By 1812 Scott’s fame as a poet and collector was such that the Grimms sent a first edition of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen to him, and this volume and several others by the Grimms still survive in his library at Abbotsford.

However, the versions of such tales that emerged in print through the hands of the Grimms and other nineteenth-century collectors became increasingly moralistic and sanitised with each new edition as the market demanded instructional literature for children. The chapbook tradition in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries offers us something quite different. Here we find a lively stream of folk and fairy tales that are earthier and less pedagogical, revealing the complex social history and adaptability of such tales.

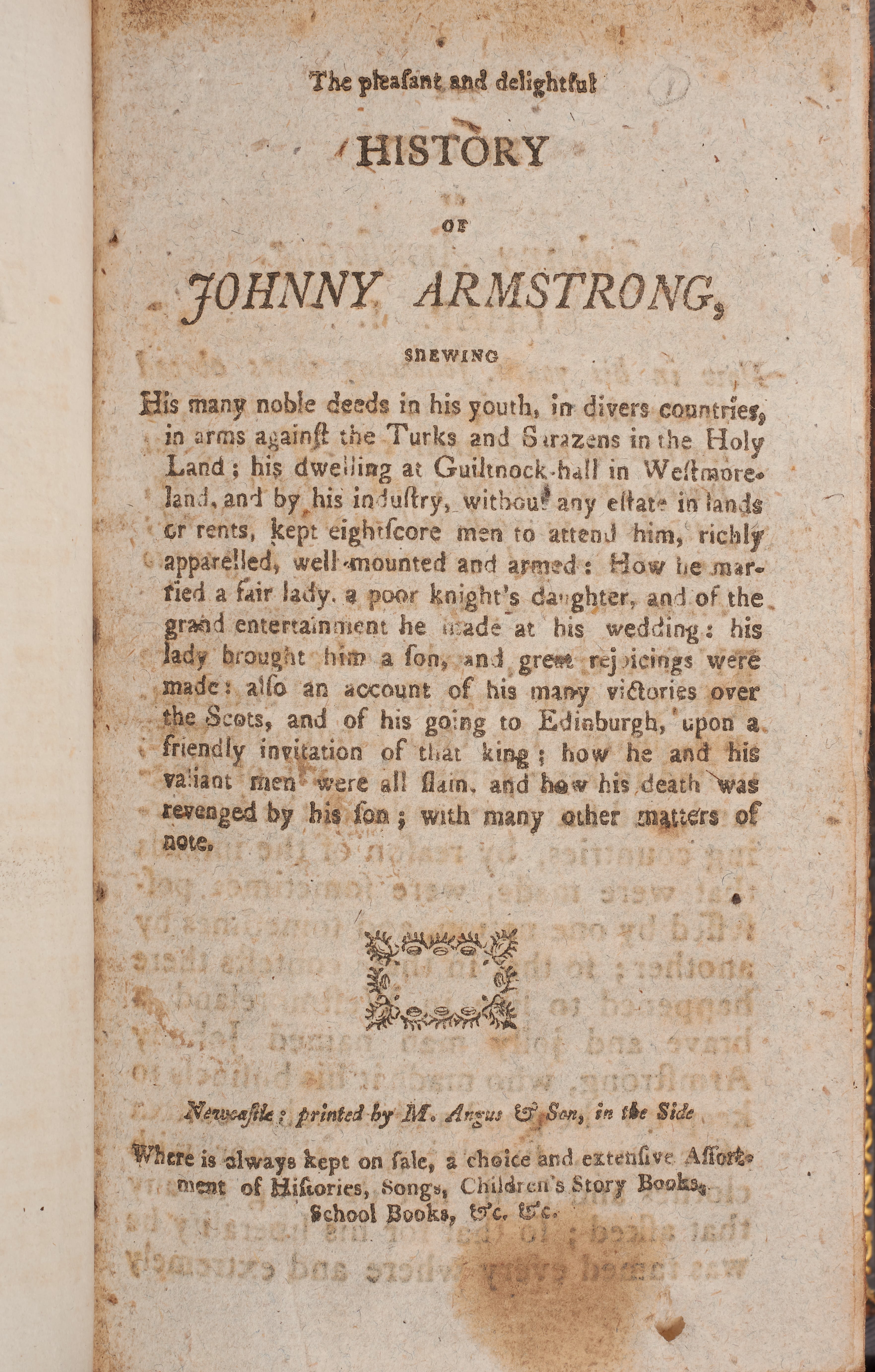

The most common fairytale material in Scott’s chapbooks includes versions of stories that are still popular today – ‘Sleeping Beauty in the Wood’, and ‘Tom Thumb,’ for example, both found in Charles Perrault’s Mother Goose, and an energetic antecedent of Jack and the Beanstalk called 'Jack the Giant Killer', a tale wildly popular in eighteenth-century Britain. Dispatching giants in Wales and Cornwall with extreme violence and guile, Jack’s status as a heroic figure of the Arthurian tradition can be understood within the context of Romanticism and the growing interest in national mythologies.

Another group of popular chapbook fairytales are inspired by the stories of The Arabian Nights, highlighting the explosion of interest in ‘tales from the East’ during the long eighteenth century.

All of these chapbook fairytales are more complicated and nuanced than the more ‘official’ versions propagated by collectors such as the Grimms, and they are very far removed from the Disney versions popular today. Many chapbook versions of ‘Sleeping Beauty’, for example, do not conclude when Sleeping Beauty’s enchanted sleep is broken. Following her marriage to the Prince, Beauty then finds herself subject to the cannibalistic scheming of an ogress mother-in-law, who plots to eat her children in a lovingly crafted sauce before turning her attention to their mother! Again, this tyrant is cannily outmanoeuvred, causing the ogress to fly into a rage, accidentally throwing herself in a vat of poisonous creatures that make their own meal of their mistress.

The darker elements of these traditional tales encourage us to consider their audiences. Several of Scott’s chapbook fairytales also contain the advertising notice that such tracts are sold alongside ‘Children’s story books’ and sometimes contain items for children that are more directly instructive, such as those designed to help them learn the catechism. However, much of the material belies the narrative that all literature for children in the eighteenth century was pious and moralistic, and also illustrates the developing cult of childhood that we associate with the Romantic period.