Exploring the University’s historic links to slavery

Matthew Lee is an AHRC-funded PhD student supervised by staff at the University of Aberdeen and the National Library of Scotland. His PhD research focuses on Scottish writers who visited the Caribbean and wrote about their experiences of slavery. As part of the project, he spent three months at the National Library cataloguing items in its slavery collections and was struck by the number of people from the North East of Scotland who were involved with slavery in the Caribbean. In this blog post he shares some of the findings from his research and how strong historic relationship to chattel slavery have shaped the very fabric of our campus in ways that can still be seen today.

Recent protests about racial injustice have given added prominence and impetus to conversations about the role that legacies of slavery and colonialism have played in moulding the world in which we live.

The connection between universities, chattel slavery and colonialism have formed an important part of this conversation. Staff and students at the University of Aberdeen should engage with these discussions given our institution’s links to the Atlantic slave trade.

The most prominent marker of these links is the Powis Gate. The gate was funded by the Leslie family after they had received compensation when slavery was abolished in Britain’s Caribbean colonies in 1834.

The gate represents an important physical legacy of slavery in Aberdeen. It stands as a testament to the fact that the proceeds of slavery flowed from the Caribbean to the North-East of Scotland.

Although its links to slavery have been given more publicity lately, it is likely that not all students and staff who walk past Powis Gate know about its provenance.

It represents a tangible link between the University and chattel slavery that is hidden in plain sight.

The relationship between the University and chattel slavery do not stop at the Powis Gate, however. The remainder of this blog will outline examples that demonstrate the deep connections between the University and slavery from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth century.

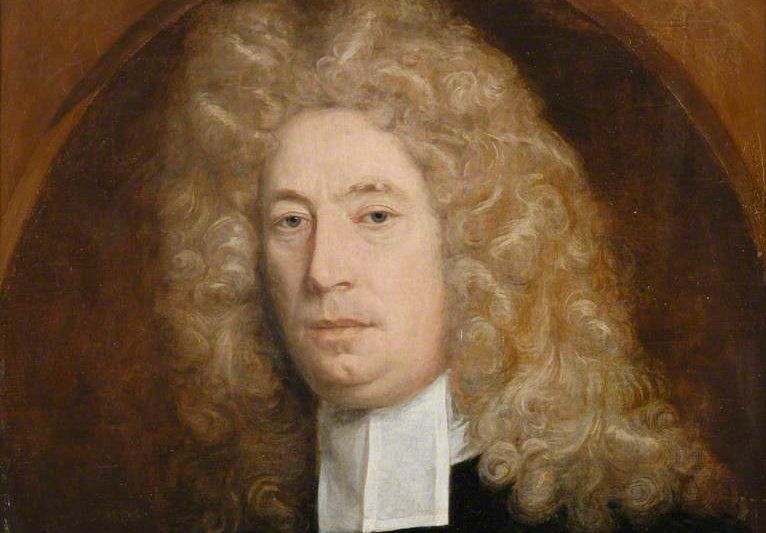

The first of these stories concerns the Reverend Gilbert Ramsay. He was an Episcopalian minister from the parish of Birse in Aberdeenshire who owned and sold enslaved people. He also left a hefty financial legacy to Marischal College.

I was lucky to be involved in a wonderful project undertaken by the present-day residents of parish that laid out the links between Birse and slavery via Ramsay.

As part of the project, pupils from the local primary school came to visit the Old Aberdeen campus and see for themselves a painting of Gilbert Ramsay in the University’s possession.

People from Birse have engaged with these local links to slavery in a brave and open way. The pupils’ willingness to engage with this complicated aspect of their village’s past is something that adults across Scotland should try to emulate.

According to the graduation rolls for Marischal College, which are available online and are a great source of information about alumni from the past, Ramsay graduated from Marischal College in 1674.

He served at St Paul’s Church in Antigua between 1689 and 1692, and at Christ Church in Barbados between 1692 and 1724. During his time in Barbados, Ramsay grew wealthy enough to leave behind substantial bequests to his alma mater and the place where he grew up.

Records held by Special Collections show that Ramsay left £3,800 – a significant sum at the time – to Marischal College in 1728. The money was earmarked to pay the salary of a Professor of Hebrew and Oriental Languages – necessary for teaching divinity – and to provide bursaries for students attending the College.

Similarly, Ramsay left money to build a parish school and establish a poor fund in Birse. The money designated for these purposes was derived from the sale of an unknown number of enslaved people.

In his will, Ramsay made clear that the enslaved people he owned were to be sold at a price below the normal market rate and the proceeds added to the rest of his estate to pay for the legacies outlined in his will.

Only one enslaved man, named Robert, was not sold. He was freed when Ramsay died. The will and the documents held by Special Collections provide details of a financial legacy, through Ramsay, between the University and chattel slavery.

Dr Gilbert Ramsay

Dr Gilbert Ramsay

‘Aye, it wis aabody’ - Published as part of the Birse Community Trust

‘Aye, it wis aabody’ - Published as part of the Birse Community Trust

The ties that bind the University of Aberdeen and chattel slavery do not begin and end with Gilbert Ramsay. Scots were prominent members of the medical profession in the Caribbean – a number of who graduated from King’s College.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, King’s College conferred medical degrees on nine individuals with ties to Jamaica. In 1820, Charles Crane was examined by doctors Alexander McLarty and Hinton Spalding – both of whom were plantation owners and enslavers on the island. Both of the current University’s antecedents were, therefore, institutions bound tightly to slavery in the Caribbean.

The graduation rolls offer more hints about the connection between the University and slavery in the Caribbean, namely the sons of enslavers who studied in Aberdeen. Amongst the graduates of Marischal College in 1817 was John Shand, the son of John Shand of Jamaica.

His brother Richard graduated from Marischal College in 1822. The records for 1837 list the graduation of their cousin Hinton Shand, who was born in Jamaica as the son of William Shand of Fettercairn (and named after the aforementioned Hinton Spalding, who was William’s friend).

William, along with his older brother John, managed and owned numerous plantations in Jamaica. The estates they owned included Clifton, Belmont, Kellits and The Burn (also the name of the Shands’ country seat in Fettercairn and is today a retreat for academics).

The plantation records show that hundreds of enslaved people lived and were forced to work at any one time on the Shands’ properties prior to 1834. When William returned to Scotland in 1823, he made The Burn the hub of his business, which operated on a global scale.

His correspondence shows that the produce grown by enslaved people on Shand’s estates in Jamaica was sold as far away as the Adriatic port of Trieste. It was the proceeds of slavery that allowed scions of planter families to be educated at Marischal College. After he graduated, Hinton Shand served in the British Army in India.

His story demonstrates the deep bonds between Marischal College, slavery in the West Indies and colonial ventures in the East Indies.

The brief examples outlined in this blog show clearly that the University of Aberdeen, through its forerunners, has a strong historic relationship to chattel slavery, which continues to shape the very fabric of its campus to this day. It is vital to unearth further examples of the University’s slavery history and to undertake to carry out reparative work to atone for the misdeeds of the past.