10. Closing Thoughts

This exhibition has aimed to celebrate and foreground the scope and diversity of Scott’s chapbook and popular print collection for the very first time.

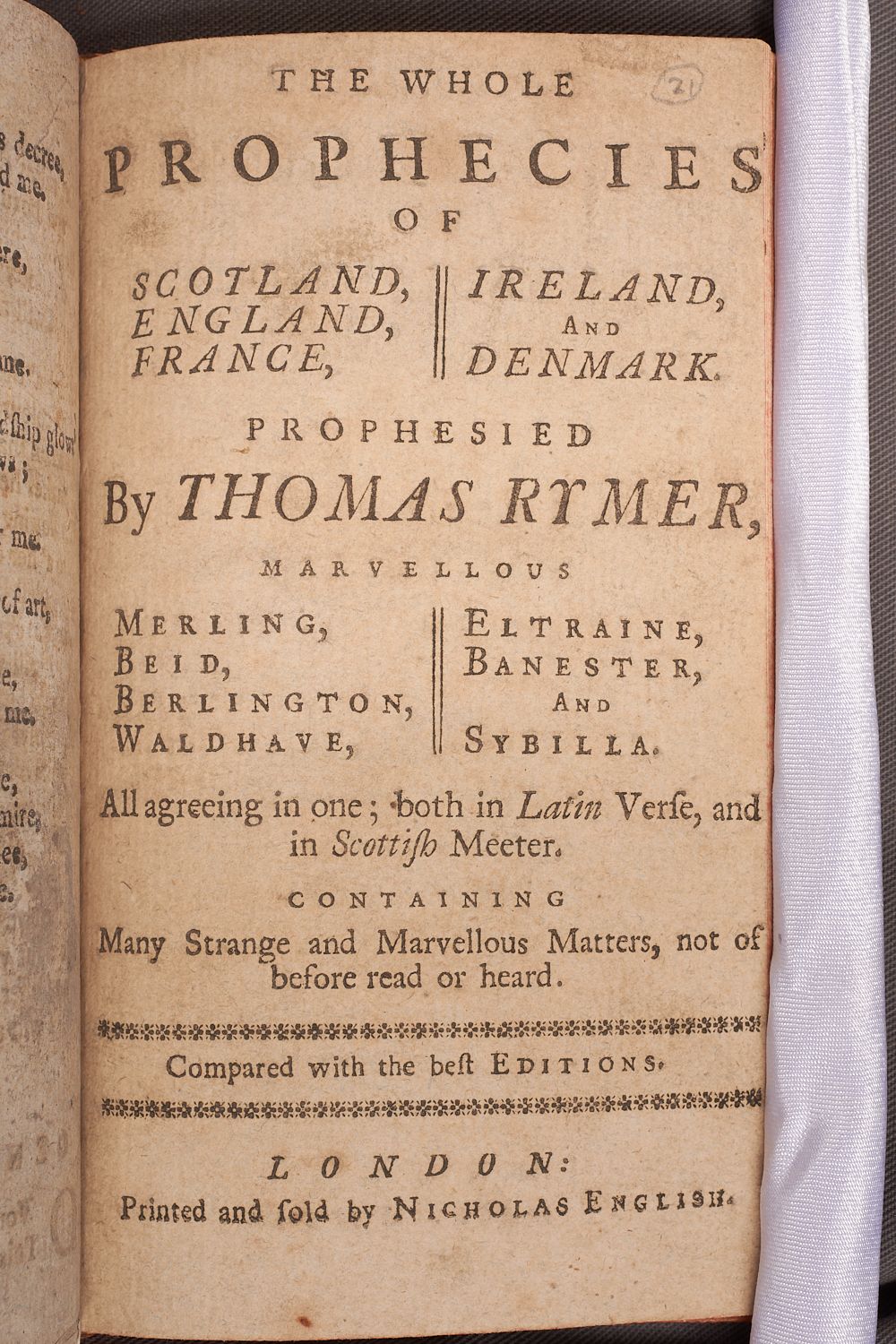

Through the generosity of the Royal Society of Edinburgh we have begun to understand the significance of the Abbotsford chapbook collection and it is clear that it provides a resource for all who are interested in politics, song, children’s literature, folk belief and print culture, both within Scotland and beyond.

There is, however, still much to be done to explore the full richness of material that Scott gathered from his boyhood onwards.

However, above all, this collection reveals to us an aspect of Walter Scott that has been previously overlooked. Often seen through the lens of his celebrity, success and perceived political beliefs, Scott today is too often positioned as divorced from everyday life, somehow only belonging to high culture. Nothing could be further from the truth, and this collection of popular print material reminds us that throughout his life Scott was fascinated by these stories and songs from the baskets of travelling pedlars, stories that see the world through the richly diverse perspective of ordinary people and their day-to-day concerns.

Moreover, these chapbooks, pamphlets and tracts were not for Scott simply antiquarian artefacts to be left on his shelves unread, but part of a living tradition that straddled the boundaries between published and oral traditions, official print culture and popular belief. For the Author of Waverley, the past and the material remnants of it, be they print material or physical object, were themselves a kind of ‘fair’, an eclectic mix of influences and media where a good story could always be found. His chapbook and popular print collection, begun when he was only ten years old, clearly provided a particularly rich resource to mine.

In a nice demonstration of the ways in which the boundaries between high and low art are far more porous than we might now believe, Scott’s own novels and poems made their way into chapbook publication in his lifetime. While Scott’s works were out of the financial reach of many people, they often encountered them on the stages of theatres and music halls. From these dramas, short chapbook versions of his work were created, and sold for around sixpence. These were completely unofficial and were not sanctioned by Scott, but his approval is evident in their survival on the shelves of Abbotsford Library, revealing his enjoyment of the intersections between official print culture and a publishing trade in ephemeral material that was part of the world of ordinary people.