3. Scott’s Chapbook and Popular Print Collection

Scott was an avid collector throughout his life and his home at Abbotsford provides a stage for the many artefacts he gathered. Walter Scott's Library at Abbotsford contains over 9000 books in addition to his considerable chapbook and popular print collections. While his chapbook collection was originally thought to contain around 100 items, this project has revealed that there are at least 2500 chapbook and popular print items in the library.

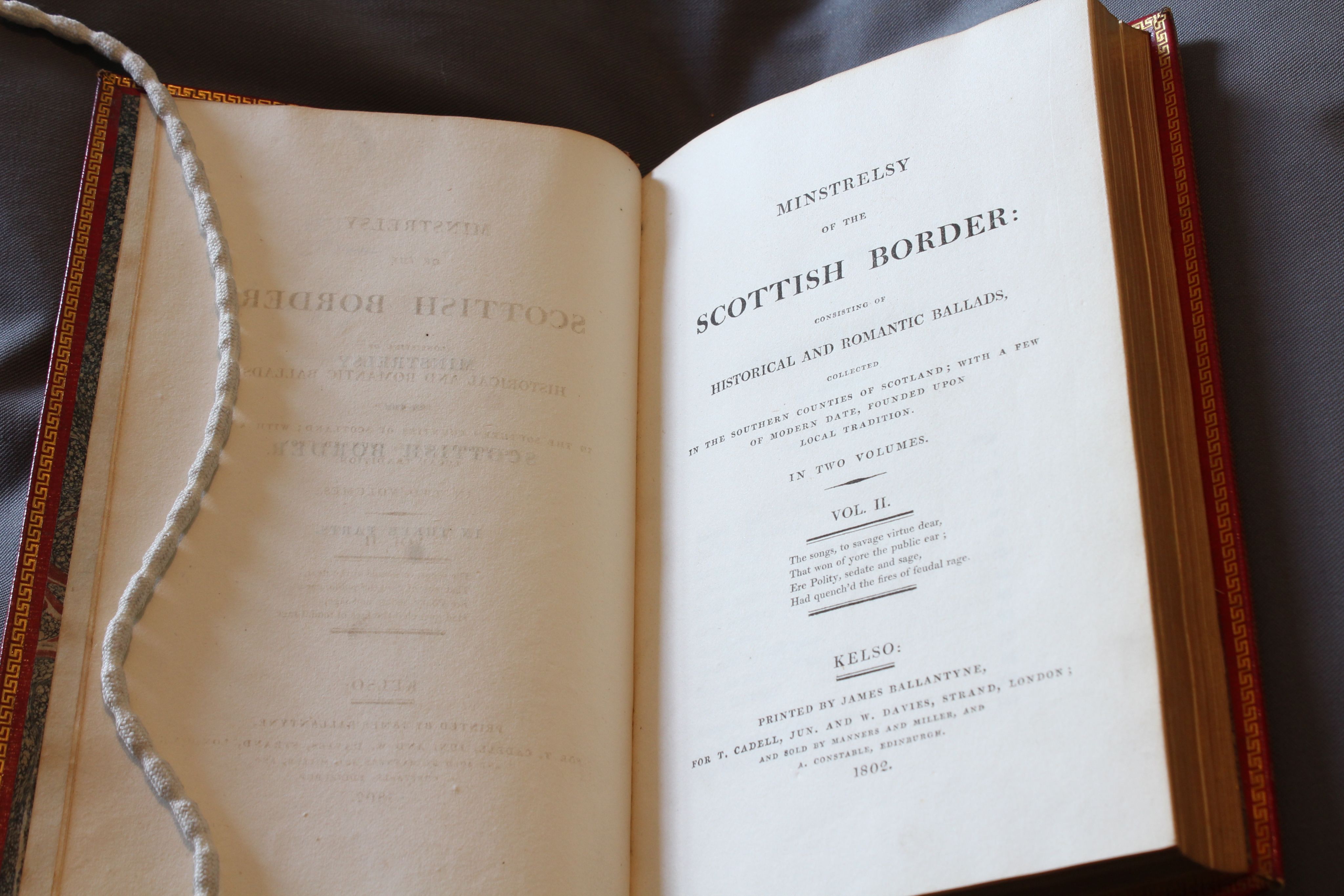

Collecting and publishing material from this oral tradition was very much in vogue in the eighteenth century, finding key proponents in antiquarians and poets such as Bishop Thomas Percy, Joseph Ritson, Alan Ramsay, Robert Burns, and indeed Scott himself; his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border was published in 1802.

Image courtesy of the Abbotsford Trust

Image courtesy of the Abbotsford Trust

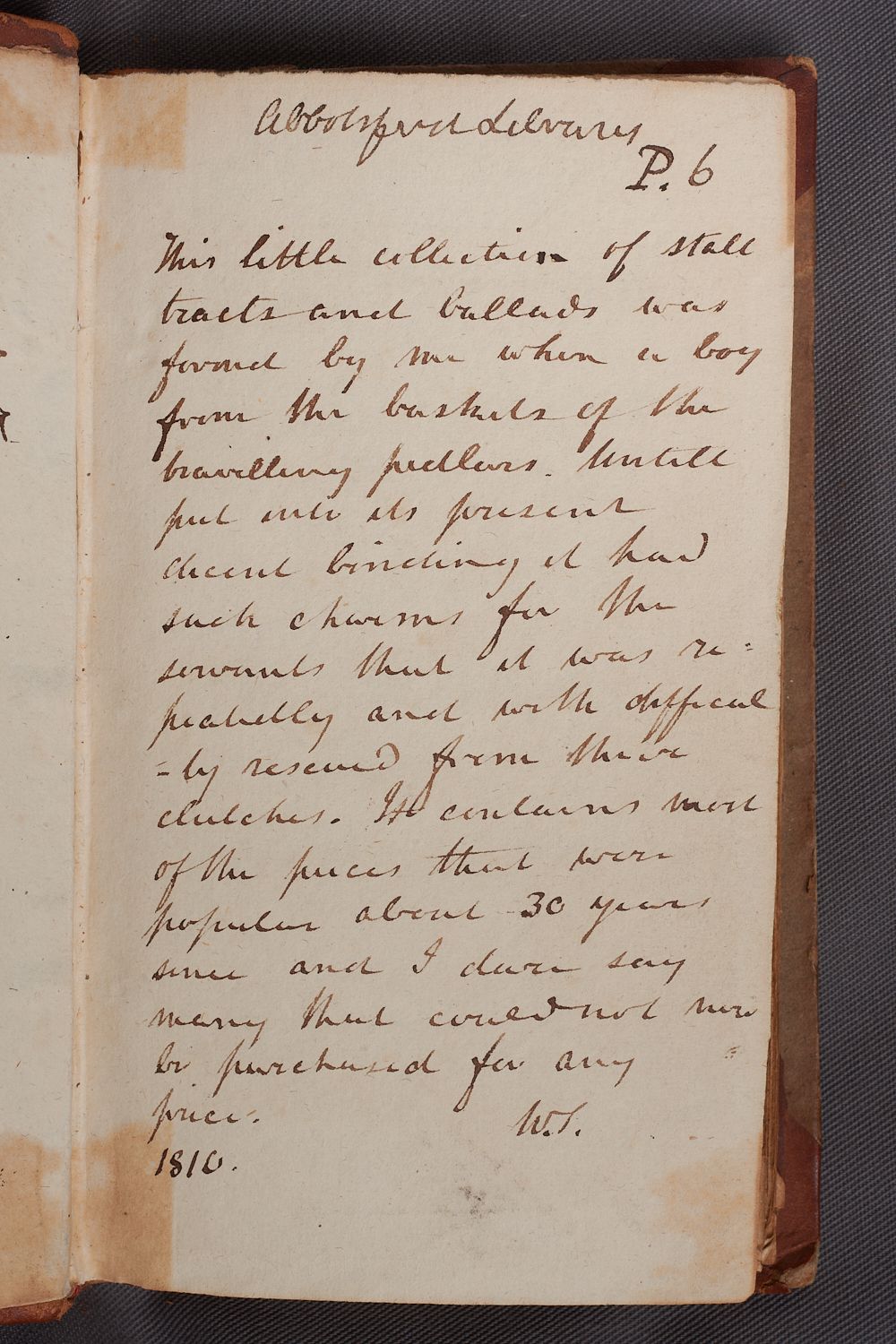

To appreciate the longevity of Scott’s fascination with chapbooks, we need do no more than turn to the man himself. Inside one of his bound collections of multiple chapbook items, he reminisces that:

What sets Scott apart from his contemporaries is that he felt this compulsion to collect and preserve them from such a young age - as a boy of just ten years old - and that chapbook versions of songs, ballads and stories played such a key role in shaping his literary appetites. While we don’t always know precisely when Scott acquired the items that now form his library at Abbotsford, it is clear that his chapbook collection expanded with age.

He explains:

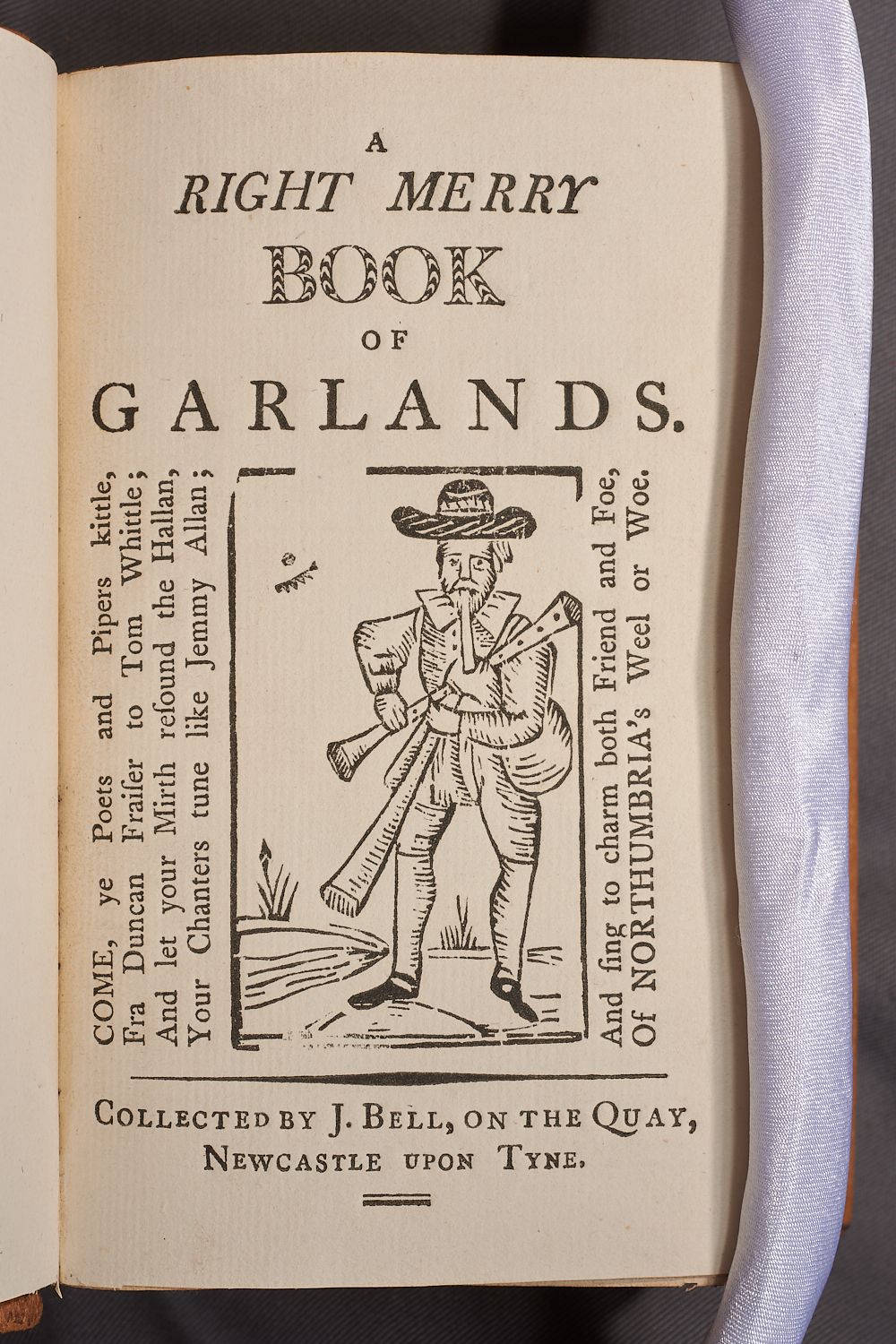

Sometimes more meaty opportunities came his way. In 1816, before much of the major building works at Abbotsford were underway, Scott acquired a haul of interesting material from the Newcastle bookseller, John Bell (1783-1864), when financial difficulties forced him to retire from book-selling. Scott admired Bell’s attitude to collecting and considered it ‘dear to a person desirous of keeping the old minstrelsy afloat’. He purchased Bell’s stock in trade of almost fifty volumes to add to his Library.

Abbotsford’s contents as a whole are peppered with larger ‘hawls’ such as this, and although buying volumes of chapbooks in this way does mean that Scott was not making conscious decisions about their contents, in a sense that is irrelevant; the joy of chapbooks is that they are eclectic. The variety of material that can sometimes appear in a single volume or even an individual chapbook beautifully captures the spirit and vibrancy of the markets and fairs where they were sold.

As we might expect from the John Bell acquisitions, nearly a thousand of Scott’s chapbooks came from Gateshead and Newcastle. Others come from elsewhere in the north of England (Durham, Penrith and North Shields, for example). A small number come from further afield, including London and Ireland. The Scottish chapbooks are printed in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Paisley, Stirling, Hawick and Haddington and other areas in the south and west of Scotland. Scott’s chapbooks are the product of a network that crosses both sides of the English-Scottish Border and it is likely that chapmen like John Cheap made similar journeys, bringing both printed and oral news with them on their travels.

That Scott saw this popular material as precious is demonstrated by the fact that he placed it in his library alongside other rare and scholarly books. Some of the material he bought, such as the Bell items, had already been bound and he preserved them in these bindings. Other items were bound for Scott and, like other books in his collection, bear his portcullis stamp on their spines. In time such material was preserved under lock and key, as Scott realised that his childhood mementoes had ‘such charms for the servants’ that he risked losing them altogether!