50 years of Art History at Aberdeen

Foundations

In 1970, the University of Aberdeen appointed David G. Irwin, of Glasgow University, to a lectureship in “Fine Art”. Over the coming years, Irwin established a History of Art Department, and degree-level teaching in this subject - bringing to fruition an endeavour that had been mooted at Aberdeen for a long time.

By 1970, the University had repeatedly considered introducing courses on the history of art in one or the other form. In 1919, the University invited Gerard Baldwin Brown, the Watson Gordon Chair of Fine Art at Edinburgh, to give a lecture series on architecture, sculpture, and painting.

Gerard Baldwin Brown, The Place of Art in Human Life, in: Aberdeen University Review (1919)

Gerard Baldwin Brown, The Place of Art in Human Life, in: Aberdeen University Review (1919)

While this was evidently more an exercise in art appreciation than in historical studies, Brown nevertheless hoped that his lectures “may create a desire for further opportunities of study, and may lead to a demand for the inclusion of Art among subjects of academic treatment”.

These ambitions were supported from within the University. One of the most vocal advocates for the discipline was the Classicist John Harrower who argued “for the inclusion of Architecture or Sculpture or Painting as a compulsory element in a liberal education”.

While the subject was well-represented in popular educational institutions, such as the Mechanics Institutes or Working Men’s Clubs, it remained absent from Higher Education.

In 1933, Harrower endowed a Professorship for Greek Art and Archaeology, named after himself and his predecessor (and father-in-law) William Geddes. This would have been the first established academic position in art history at Aberdeen - but the Second World War put these plans on hold.

Douglas Strachan, John Harrower (oil on canvas, 160x108cm, University of Aberdeen), 1914

Douglas Strachan, John Harrower (oil on canvas, 160x108cm, University of Aberdeen), 1914

By the time the University hoped to capitalise on Harrower’s bequest, inflation had wiped out most of the funds. The Geddes-Harrower Professorship was thus converted to a biennial Visiting Professorship, attracting some of the most renowned names in the field to Aberdeen.

The first incumbent, in 1961, was Bernard Ashmole, a leading historian of Greek sculpture. By this time, the University clearly considered in earnest to expand its provision of art historical teaching, beyond the already existing courses in “Drawing and Painting” (which also included classes in “art appreciation”) that were available as part of educational degrees. In 1961, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner conducted a survey about the state of teaching of Art History in British Universities; Aberdeen replied that the subject was currently “not taught, but planning to introduce”. Nine years later, with Irwin’s appointment, the first step in this direction was taken.

A.D. Trendall, Greek Art. Notes and references for a course of eight lectures, 1966, Special Collections, Sim HA Eu Gre T

A.D. Trendall, Greek Art. Notes and references for a course of eight lectures, 1966, Special Collections, Sim HA Eu Gre T

The 1970s: Growing a department

At first, Aberdeen University was still uncertain about the name of the new field. A selection committee, formed in late 1969, hoped to recruit a lecturer in “Visual Arts”. Early the following year, David Irwin was hired as Lecturer in “Fine Art”, and it clearly was his initiative to christen the new programme under the more modern and recognizable name “History of Art”.

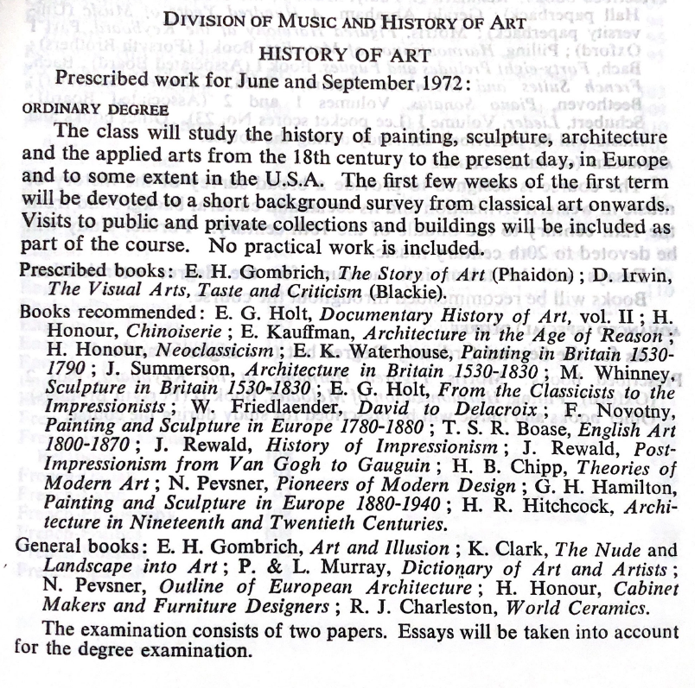

In 1971, Aberdeen offered for the first time an ‘ordinary’ (first year) course in History of Art – thus inaugurating the subject at the University. To avoid confusion, the course catalogue stated clearly: “No practical work is included”.

History of Art - University Calendar 1972

History of Art - University Calendar 1972

Art History as an independent academic discipline began to find its feet at Aberdeen. This was helped by another hire, in 1971, of a second member of staff, David Mannings, a specialist on British portraiture of the 18th century. From a modern perspective, the decision to hire two historians of British Art of the 18th century might look surprising. However, this policy was very much in tune with the development of the discipline elsewhere. In the late 1960s, art history departments were springing up in many British cities, whether in ancient universities or the new “plateglass universities”. The decision to focus on the – hitherto often neglected – history of British Art seems to have been a clear decision to position the subject in a way that would complement existing and popular degrees in English and History. Well into the 1970s, art historians such as Hamish Miles argued in fact that the discipline should not become a stand-alone undergraduate degree, but provide optional modules for students from other fields.

Like for many other departments, running a full degree course was initially not an option anyway for the small team at Aberdeen. But already in Spring 1971, the University Court resolved that History of Art should also offer courses on Advanced Level (Year 2), which necessitated a further member of staff. In 1972, the University hired John Gash, who had recently graduated with an MA (supervised by Anthony Blunt) from the Courtauld Institute. Since 1974/75, the Department also offered honours teaching, thus establishing a full degree-course in art history.

In 1975/76, for the first time eight students graduated from Aberdeen with a degree in History of Art. Then, as today, contemporary art proved to be a big draw, and dissertation topics covered Dada and Surrealism, David Hockney, or Stanley Spencer – but also more historical fields such as Sea Painting in Scotland, James I and the Spanish Match, or Classical Revival Country Houses. The young department had bedded in successfully, and its continuous appeal with students soon required further investment in staff. In 1977, the department complemented its teaching offerings by hiring two historians of Medieval Art, Tessa Garton (a specialist in Romanesque sculpture) and Donal Byrne (a historian of Gothic manuscripts), who both joined Aberdeen from University College Dublin.

The teaching offerings were, from the beginning, remarkably varied, incorporating areas such as contemporary art or industrial design. From its inception, the Department was committed to bringing students in touch with original artworks, in Scotland and abroad. Since the 1970s, the lecturers organised regular trips to Scottish collections, such as the National Gallery in Edinburgh. Much of this fieldwork was conceived as independent study, with Honours candidates being “required to spend four weeks abroad during a vacation studying works of art in Europe”.

Teaching Materials “Pop Art”, 1971

Teaching Materials “Pop Art”, 1971

David Irwin

This is perhaps the appropriate moment to focus briefly on David Irwin, the Department’s founding father. His life and career are, in many respects, a representative example for the development of art history as an academic discipline in post-War Britain. His research interests, however, make him an exceptional and intriguing historical figure that runs counter to what is often associated with British art scholarship.

David Irwin, The Visual Arts. Taste and Criticism, 1969

David Irwin, The Visual Arts. Taste and Criticism, 1969

Irwin was part of a new generation of professionally trained art historians. Up until the foundation of the Courtauld Instititute in 1933, no formalized training in the subject was provided at British universities. In a time where most art historians were still self-taught, Irwin was somewhat of an exception who even held a PhD: his thesis on Neoclassicism was supervised by Anthony Blunt at the Courtauld. This remained his main research interest throughout his life, resulting in seminal book publications spanning from “English Neoclassical Art” in 1966 to “Neoclassicism” in 1997 – a textbook that is still much-used. But Irwin’s interests ranged much more widely; his monograph on “Taste and Criticism” discussed a wide range of works from visual culture and design up to the present day. He also reviewed for example an astonishing number of books on contemporary art. In 1971, in a review of an anthology on Minimal Art, he concluded: “Minimal Art is so obviously the most important movement of the 1960s, and equally certainly will continue to be so in the early 1970s.” Such a bold embrace of controversial modernist tendencies in art was highly unusual for the time, where such movements had little if any place in academic art history. In a time where most of his peers focused almost exclusively on being the ‘expert’ on one particular artist or artistic school, Irwin’s intellectual curiosity stands out.

Many of Irwin’s projects were developed and pursued in collaboration with his wife Francina Irwin, herself a highly regarded art historian who also, for periods, taught at Glasgow and Aberdeen.

Together, they published a pioneering volume on “Scottish Painters at home and abroad, 1700-1900”, for the first time mapping this largely neglected terrain of art history. Irwin had a keen interest in fostering the art scene in Aberdeen, and argued vocally for the necessity of a dedicated university museum.

Perhaps even more unusual for British art history in the 1970s, Irwin also had a sustained interest in art writing and questions of methodology.

David Irwin

David Irwin

In 1972, he published a seminal selection of the writings of the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, still widely read and used today. Such interests stood in stark contrast to the mainstream of British art writing, dominated by a positivist and connoisseurial attitude towards art.

These interests perhaps also motivated the hire of David Mannings, who joined the fledgling department in 1971, and who was a regular contributor to the British Journal of Aesthetics, publishing for example seminal articles on “Panofsky and the Interpretation of Pictures” (1973). With this first hire, Irwin clearly underlined the department’s commitment to a dynamic discipline, and an interest in methodological discussions.

The 1980s

In many respects, the department’s development in the 1970s mirrors the radical changes and astonishing growth that characterized British Higher Education as a whole in this period. The following decade proved much more challenging for the Department, and the University as a whole. In 1981, Margaret Thatcher announced substantial cuts to government funding – more or less the only source of income for most universities. Aberdeen, like many other institutions was hit hard; in the same year George McNicol took over as Principal, overseeing the process of ‘change management’, and leading to a decade-long decline for the humanities at Aberdeen. A first round of cuts did not manage to balance the books, and by 1987 the University was facing a dire situation. The Principal announced severe cuts, proposing the closure of a whole raft of disciplines, from Music and Italian, over Classics to Physics. Other departments such as History faced severe cuts in staff numbers. History of Art was equally in the firing line.

Emergency Gaudie, Wednesday 25 May 1988

Emergency Gaudie, Wednesday 25 May 1988

The Department nevertheless retained strong student numbers: in 1988 the department had an intake of 87 students on its first-year course, who encountered a varied teaching programme. Honours options offered students a full chronological spread, from Classical Art (a survival of the Classics department, closed in the late ‘80s), Romanesque Art and British Medieval Art, over 17th-century Art in England to French Modernism (1880-1935) and Industrial Design, “taught right up to the present decade”. The social highlight of the year remained the annual visit to The Burn, a country house near Edzell, where students conducted group work on contemporary and controversial issues such as “Does curatorial exploration murder aesthetic delight?”

“87:4 So few so many”, The Gaudie

“87:4 So few so many”, The Gaudie

The financial pressures nevertheless eventually impacted on the personal and administrative shape of the Department. With the ongoing threat of redundancies hanging over the heads of members of staff, Tessa Garton left Aberdeen in 1988 to take up a professorship at Charleston College in the United States. Tragically, in the same year Donal Byrne passed away at the untimely age of 45. History of Art had shrunk to four members of academic staff. The cuts also affected the administrative organization of the humanities at Aberdeen. Plans to regroup numerous subject areas (including Divinity, the University’s founding school) were hotly debated, with many academics fearing for the independence and integrity of their subject areas. But changes were coming: in November 1988, the University Senate agreed that “a School of Historical Studies be established within the new Faculty of Arts and Divinity incorporating the Departments of History and History of Art”. Other smaller Departments such as Cultural History and Economic History were also merged into this new unit. The attempts to realign disciplines was also underlined by new, joint hires, clearly intended on consolidating the new administrative structures. In 1989, a new medievalist, Louise Bourdua, was hired on a lectureship shared between History and History of Art.

Donal Byrne, Notes for visit to the Burn, Special Collections

Donal Byrne, Notes for visit to the Burn, Special Collections

Renewed growth - The Quincentenary and beyond

As so often, the Art History Department’s fortunes changed in tune with the University’s as a whole. In 1991, John Maxwell Irvine took office as the new Principal, leading the University towards its 500th anniversary in 1995, a milestone that was prepared with ambitious fundraising campaigns and renewed investment.

David Mannings book launch

David Mannings book launch

In the early 1990s, the History of Art Department virtually doubled in size. Dr Louise Bourdua, first appointed jointly with History, transferred to a full position with History of Art; Dr Jane Geddes, a medievalist who became a leading authority on Pictish Art, was also appointed to a full-time position, after teaching at the department for multiple years in smaller capacities.

Critical Perspectives – course cover

Critical Perspectives – course cover

Additionally, the Department hired Dr John Morrison, who had recently graduated from St Andrews with a thesis on “Rural Nostalgia” in nineteenth-century Scottish Art. Another appointment was Dr Tom Nichols, a specialist on Venetian Art. These appointments consolidated the Department's expertise in British and Italian Art. In the early 1990s, the Department now had reached its biggest period of growth, with seven full-time members of staff, and offering up to eight honours courses per year.

In 1997, David Irwin retired after 25 years as Head of Department. In many respects, this date also marks the transition into a changed environment in British academia. The significance of new benchmarking exercises such as the “Research Assessment Exercise”, as well as internal “Teaching Quality Assessments” became increasingly significant, requiring an unprecedented degree of reflection and strategic planning for the years ahead. In particular the RAE attested the Department to be in good health.

These submissions also document the shifting organizational alignments of the Department within the University. While History of Art submitted independently to the RAE 2001, the Department joined forces with Film Studies for the RAE 2008, underlining a “focus on multi-disciplinarity” and promoting a “refocusing on visual culture”. For the REF 2014, the Department pursued different priorities and submitted together with History.

The turn of the millennium also saw the delivery and publication of several long-term projects, such as Jane Geddes’ “Medieval Decorative Ironwork in England” (1999), and David Mannings’ catalogue raisonnée of the paintings of Joshua Reynolds, co-authored with Martin Postle (2000).

The latter in particular is an interesting case study of art historical research ethos of the period, negotiating between traditional approaches, and a methodological openness to new debates in the ‘New Art History’ of the 1980s.

On the one hand, cataloguing the paintings of the Royal Academy’s founding president was a hugely traditional project resonating with the old establishment of British art scholarship. Yet at the same time Mannings championed the ‘new art history’ represented by controversial authors such as David Solkin, and commented pithily on the ‘patricians’ who tax pictures merely with positivist questions of attribution in mind.

New Art History

Like Mannings, the Department as a whole attempted to strike a balance between canonical fields of expertise and innovative new growth areas. On the one hand, the Department cultivated its traditional strengths in Medieval and Early Modern art. On the other hand, it also aimed to situate this material in a wider context: in the 2000s, the Department made a number of appointments in areas such as Eastern European Art (Shona Kallestrup, Amy Bryzgel), the Global Baroque (Peter Davidson, Gauvin Bailey), and even contemplated to provide teaching in Chinese Art.

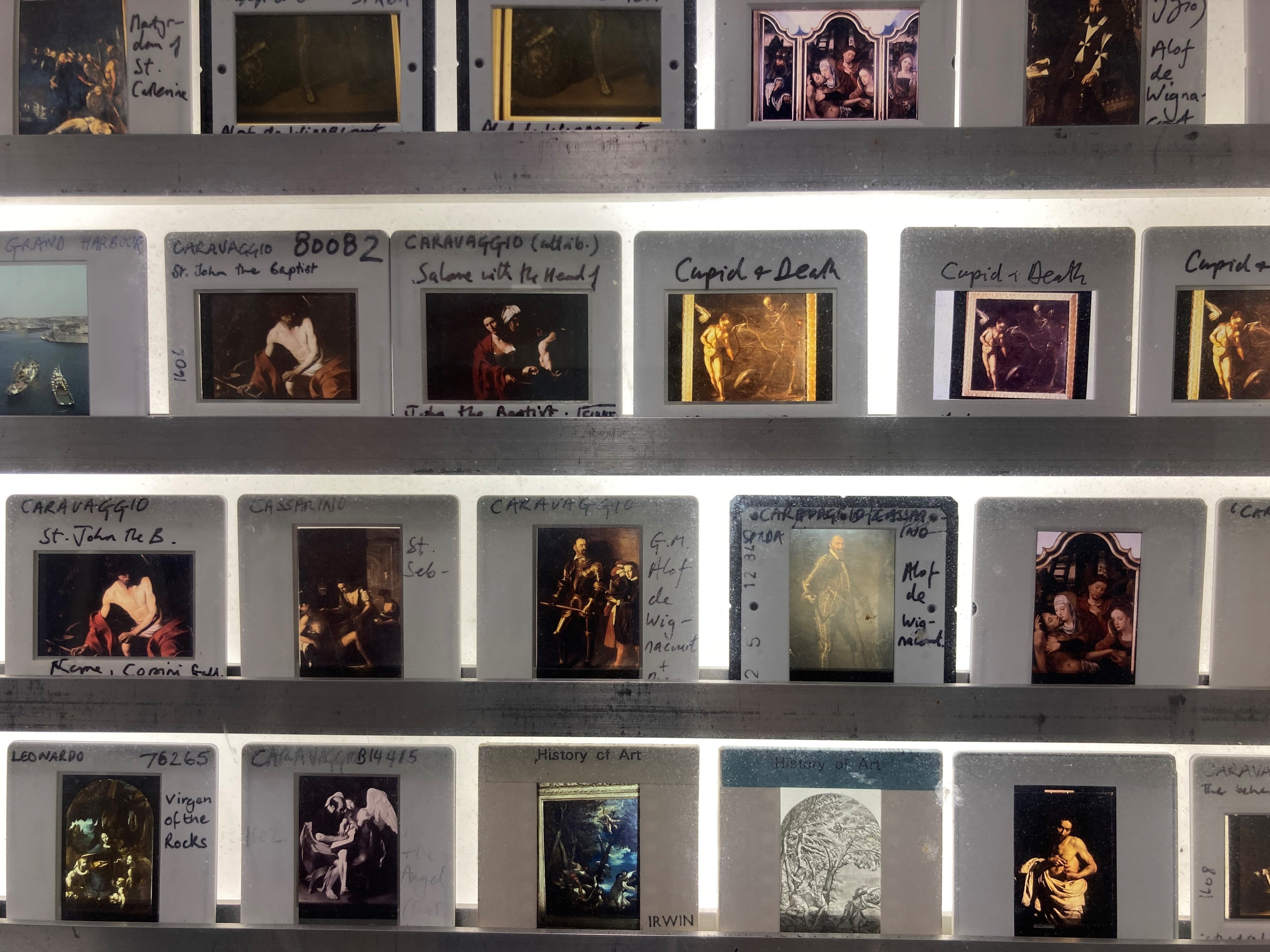

Slides of Chinese art

Slides of Chinese art

Perhaps more than other humanities, art history also was affected by the impact of digitization early on since visual material played a key part in education and research. Traditionally, the slide library was a key resource, at the heart of every art history department. Since 1994, Jane Geddes had supervised the creation of a computer catalogue for the slide library; in the 2000s, the images themselves became increasingly digitized. Aberdeen was, in many respects, at the forefront of these developments; the Department embraced the change and experimented with innovative tasks: as early as 2003, John Morrison assessed his courses by means of asking students to design webpages.

Slide Display cabinet

Slide Display cabinet

The possibilities of the digital age were equally embraced on the research side of things. In particular Jane Geddes launched a series of initiatives that led to pioneering hybrid publications. In 1996, she directed a digital edition of the “Aberdeen Bestiary”, a lavish medieval manuscript and one of the biggest treasures of the University’s Special Collections. This was followed in 2003 by a digital edition of the “St. Alban’s Psalter”, which also became the subject of a highly successful exhibition. This project was made possible by a substantial grant by what was then the “Arts and Humanities Research Board”. In subsequent years, the Department succeeded with a number of such bids for substantial research funding, leading for example to the publication of two volumes on Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire for the series “Buildings of Scotland”.

St Alban’s Psalter – Digital edition

St Alban’s Psalter – Digital edition

Throughout its 50-year history the History of Art Department at Aberdeen was characterised by long-standing service. Leading the count, with an astonishing 47 years of service, is John Gash (1972-2019). Jane Geddes’ and John Morrison’s ‘mere’ 31 and 29 years respectively might seem short compared to that, but are nevertheless fast becoming a rarity in modern-day academia. In the late 2010s, this resulted in a series of retirements and other departures that led to a number of new hires. This also resulted, in 2021, in a name change for the discipline which now called “Art History”, instead of “History of Art”. Art History, as Griselda Pollock wrote in 2014 designates the discipline as distinct from its field of study. While the Department remains chiefly concerned with the history of Art, the name change reflects an openness to other areas of visual history. The distinction drawn between discipline and field of study is particularly relevant in light of the broader challenges in the 21st century – human rights, environment and sustainability.

It helps us to think about our discipline as inclusive and intellectually open; one that embraces diverse sub-fields, methods and approaches in both research and teaching. It places emphasis on our interdisciplinary profile whilst remaining recognisably about art - in its widest definition - and its complex histories enacted over time and space.