A vision to feed the world

Celebrating Rowett Institute founder John Boyd Orr

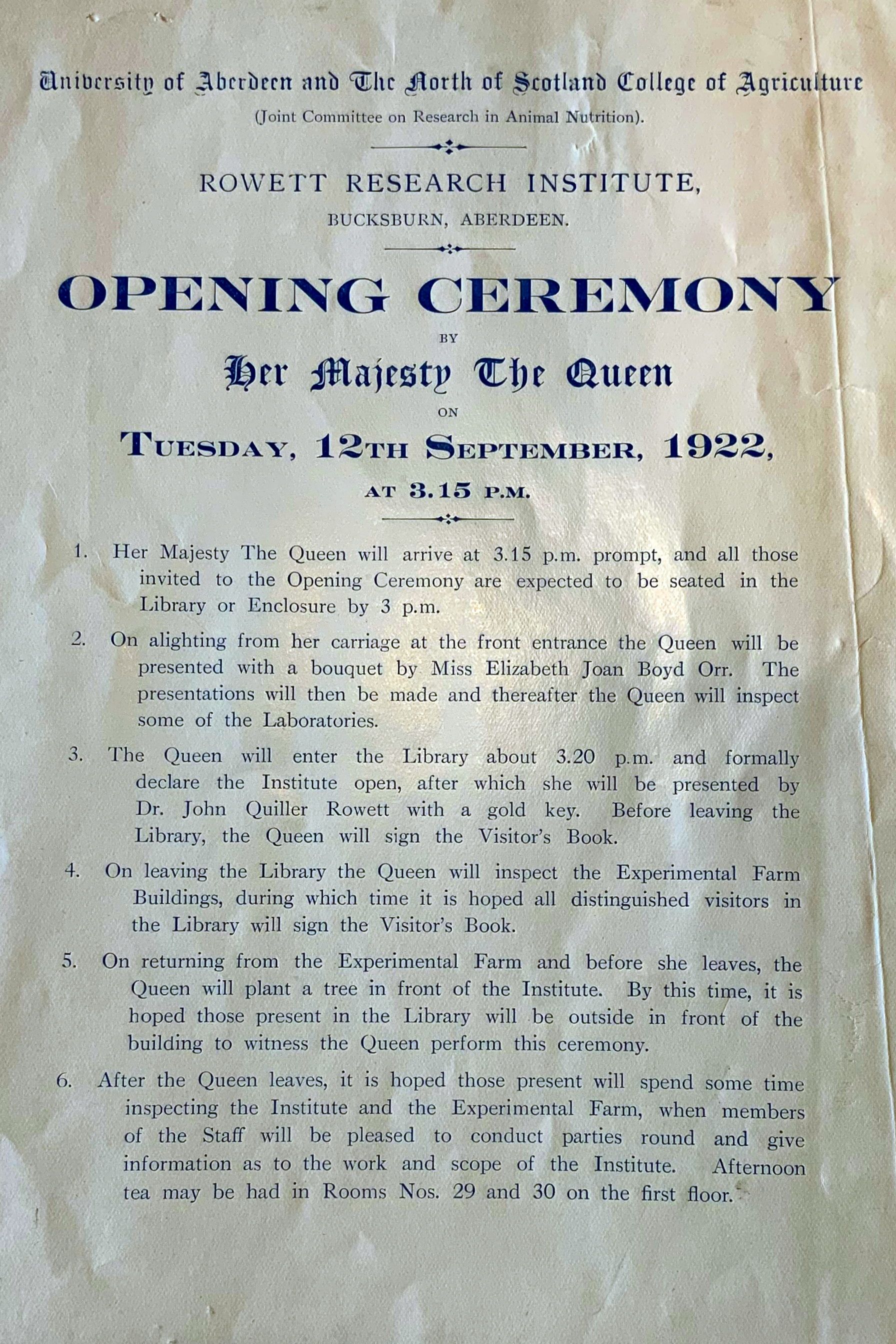

When Queen Mary cut the ribbon on a new Aberdeen institute on September 12, 1922, it would mark the start of a century of research to improve both animal and human health.

Since its laboratories first opened, the University’s Rowett Institute has contributed to improving national health through free school milk, underpinning wartime rationing and improving agricultural production. Today its impact remains global, supporting the food and drink industry to produce healthier foods, changing consumer behaviour and assessing the sustainability of the food we eat.

But the Rowett’s important contributions across a century have been driven by the ambition of its founder, John Boyd Orr. His determination, intellect, eloquence and skills in persuading benefactors to part with considerable sums of money transformed the modest premise on which the institute was formed, enabling it to grow into a world-leading centre of research, which continues to play a key role on the world stage a hundred years after Queen Mary officially declared it open.

We explore the extraordinary life and achievements of a man who earned the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort to “conquer hunger and want, thereby helping to remove a major cause of military conflict and war”.

Education through enterprise

John Boyd Orr was born on 23 September 1880 at Kilmaurs, Ayrshire, the middle child of seven.

He attended a local school when the family moved to West Kilbride until he was 13 when he won a bursary, rare in those days even in Scotland, to Kilmarnock Academy.

But he was more interested in the life of the navvies and quarrymen who worked in his father’s business than in his education and so was returned to the village school where, at the age of 18, he became a teacher.

Aided by scholarships, he was able to attend simultaneously a teachers’ training college and the University of Glasgow.

It was a condition of his scholarship that after successfully completing his training course he should teach for a certain period. To fulfil this obligation, after he graduated M.A. in 1902, he applied to the Glasgow education authority and was posted to a school in one of the most deprived parts of the city.

The overcrowded and squalid conditions were a far cry from his countryside upbringing and, realising the impact of their impoverished conditions on his pupils’ ability to learn, after just a few days he tendered his resignation. Orr moved to Kyleshill School in Saltcoats where he remained for three years and enjoyed success coaching students through the university examinations.

But his teacher’s salary was low and so to augment this, he saw an opportunity to instruct local evening classes in book-keeping and accountancy. Undeterred by not holding the necessary qualifications, he embarked on intensive study and passed the necessary examinations – acquiring skills which would serve him well later in life.

His heart was not in teaching and, now in his mid-twenties, he decided to return to university to study biological science and medicine.

Part way through his courses finance became a problem so, with the small capital of £5 remaining in his savings and a large overdraft from a bank, he bought a block of tenanted flats on mortgage. The rents covered his university expenses and, when he graduated with his medical degree in 1912, having already acquired a BSc in 1910, he sold them for a small profit.

To clear the remainder of his overdraft, Orr took a job as a ship’s surgeon before accepting an offer of a two-year Carnegie research scholarship, to work in the laboratory of Scottish physician and physiologist E. P. Cathcart, exploring undernutrition and the energy expenditure of infantry recruits in training.

A bold choice

It was E.P Cathcart that a Joint Committee for research in animal nutrition of the North of Scotland College of Agriculture and the University of Aberdeen had in mind when a new post was created to develop research in this area.

But before he could take up the role, Cathcart was offered a chair of physiology in London which proved more attractive. He advised the Principal of the University of Aberdeen, who chaired the Joint Committee, that Boyd Orr be appointed to the position instead.

It was a bold move as upon being told at interview that the new post involved the running of a small research institute, Orr told the Committee that he had not the necessary experience!

Nevertheless, he was offered and accepted the position. He arrived in Aberdeen on April 1, 1914, a very fitting day for, as he recorded in his autobiography*, when he asked where the nutrition institute was, he discovered that it did not yet exist!

Instead, a sum of £5,000 had been set aside to construct a wooden laboratory building at Craibstone, north-west of Aberdeen, with a further £1,500 annually for staff salaries and maintenance.

A grand ambition interrupted by war

Orr considered the package on offer to be inadequate to support his ambitions for the institute and immediately set about transforming the plans. His estimates for the scale of what was required totalled more than ten times his initial allocation.

Within his £5,000 budget he costed and instructed a building of granite, rather than wood and by the time the committee next met, the walls of his new building, deliberately designed as the wing of a larger institute, were already six feet high.

But the swift progress was interrupted by war. Keen to offer his services, Orr enlisted: initially assisting with improving sanitation in barracks before serving in the trenches as a medical officer to the 1st Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters.

At the Battle of the Somme his battalion suffered heavy losses. Its strength was reduced from 800 to about 200 in just 24 hours, with the loss of nearly all of its officers.

When those who remained were moved back from the frontline to boost numbers with new recruits, Orr took the opportunity to improve their health through diet.

He sent out a fatigue party to collect vegetables from the abandoned gardens and fields surrounding the battlefield.

As his biography** notes, “as a result, from the men in his medical charge he had to send none to hospital, whereas units who relied on their army rations without such supplements were much less fortunate.”

Orr was also successful in reducing trenchfoot among his men by ensuring they were fitted with boots a size larger than usual.

He continued to serve as medical Officer at Ypres and then at the Battle of Passchendaele, his courage under fire earning him both a Military Cross and Distinguished Service Order.

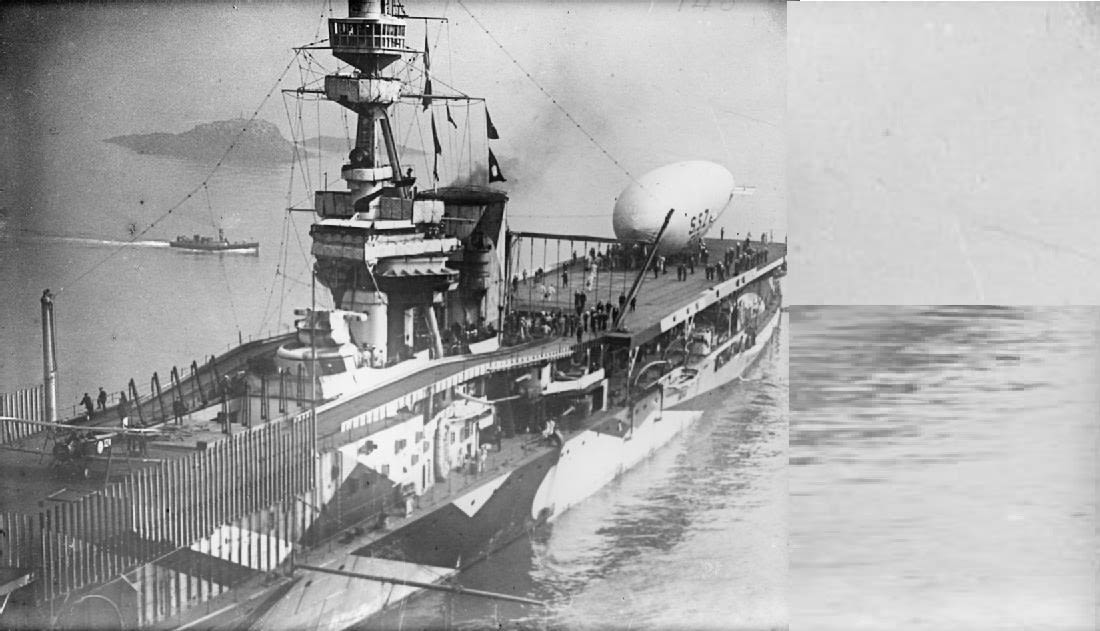

Orr completed the remainder of the war with the Navy serving in hospital wards and on board HMS Furious.

As soon as the Armistice was signed, he was keen to return to Aberdeen to check on the progress of the building he has authorised back in 1914 – without the prior approval of the Committee!

The house that Boyd Orr built

Orr found that the walls and roof of the granite building had been completed but there had been no acceptance of his idea of a larger ‘Institute for Nutritional Research’.

He appointed his first three staff and in the weeks that followed his return this small team – Orr included – used their own hands to fit the new laboratory with benches and equipment and in their lunch-hour constructed an access road to the building from a near-by farm road. By midsummer 1919 all was complete.

But Orr was not prepared to settle for such a small-scale facility and he continued to push for a properly equipped new research institute.

Finally the Government agreed to pay half the costs but only if the other half could be found from other sources.

Orr soon put his persuasive powers to good use when introduced by fellow scientist Robert Henry Aders Plimmer, who had recently been appointed as the research institute’s biochemist, to an old school friend who was visiting him in Aberdeen in 1920.

The friend was John Quiller Rowett, a businessman and director of a wine and spirit merchants in London which had profited substantially from the war.

Keen to give back and with an interest in agricultural improvement, Rowett was impressed by Orr’s ambitions for the nationally important functions that an enlarged research institute on lines that he had already planned would serve.

His donation of £20,000 allowed the purchase of 41 acres of land at Bucksburn for the Institute to be built on and also contributed towards the cost of the buildings. The money was donated with one very important stipulation from Rowett — "if any work done at the Institute on animal nutrition were found to have a bearing on human nutrition, the Institute would be allowed to follow up this work."

Orr lost no time in going forward with the already-planned buildings and by September 1922 they were nearly completed.

But when the chair of the Joint committee informed Orr that Queen Mary had agreed to come over from Balmoral to conduct a formal opening, a last-minute rush ensued as the facilities were far from ready for such a significant ceremony.

Importantly, there was not an adequate complement of animals available to fill the uncompleted pens. According to local legend, during the opening ceremony the Queen said that the sheep looked tired. They were - they had been travelling all night to provide enough animals for the opening!

The Rowett Institute in 1922

The Rowett Institute in 1922

Queen Mary on a tour for the Royal opening

Queen Mary on a tour for the Royal opening

The programme for the official opening

The programme for the official opening

Improving the health of a nation

Professor Peter Morgan, Director of the Rowett from 1999 to 2021, says Rowett’s stipulation, in combination with Orr’s own medical interest, soon led to an expansion of the Institute’s initial remit, which was to examine the mineral content of pastures and the importance of vitamins and minerals in the

diet of farm animals towards human health.

“As a medic, Orr was able to run his own research interests in parallel with the research the Institute was originally set up to undertake,” he adds.

“In the late 1920s, Orr began to look at the relationship between poverty, food and optimal health. His research changed our understanding of the relationship between diet and health – he was the first scientist to show that there was a link between poverty, poor diet and ill-health.”

This was first demonstrated as Orr became dismayed by waste in the dairy industry, which since the beginning of the decade had been producing a significant surplus.

Orr set up experiments on the value of milk to school children and found there was a marked improvement in their health and growth, particularly among those from the poorest households.

His findings later underpinned a parliamentary bill to provide school children with free milk and spurred his desire for a ‘a comprehensive food and agricultural policy based on human needs which would absorb all home-produced surpluses’, for which he lobbied hard throughout the early 1930s.

To support this, Orr led a desk study on ‘Food health and Income’, which classified the UK population into six groups according to income and then estimated the adequacy of the diet consumed in each of the groups.

The study showed that more than one third of the population were too poor to purchase an adequate selection of foods to maintain health.

So great was the interest in the 1936 study that the Carnegie Trust gave the Rowett a grant of £15,000 to carry out a more detailed study. More than a thousand families, including 3,000 children, took part across Scotland and England between 1937 and 1939.

Detailed information was gathered on the socioeconomic status of each household and diet and analysis of data from the Carnegie survey was in progress at the Rowett when war broke out.

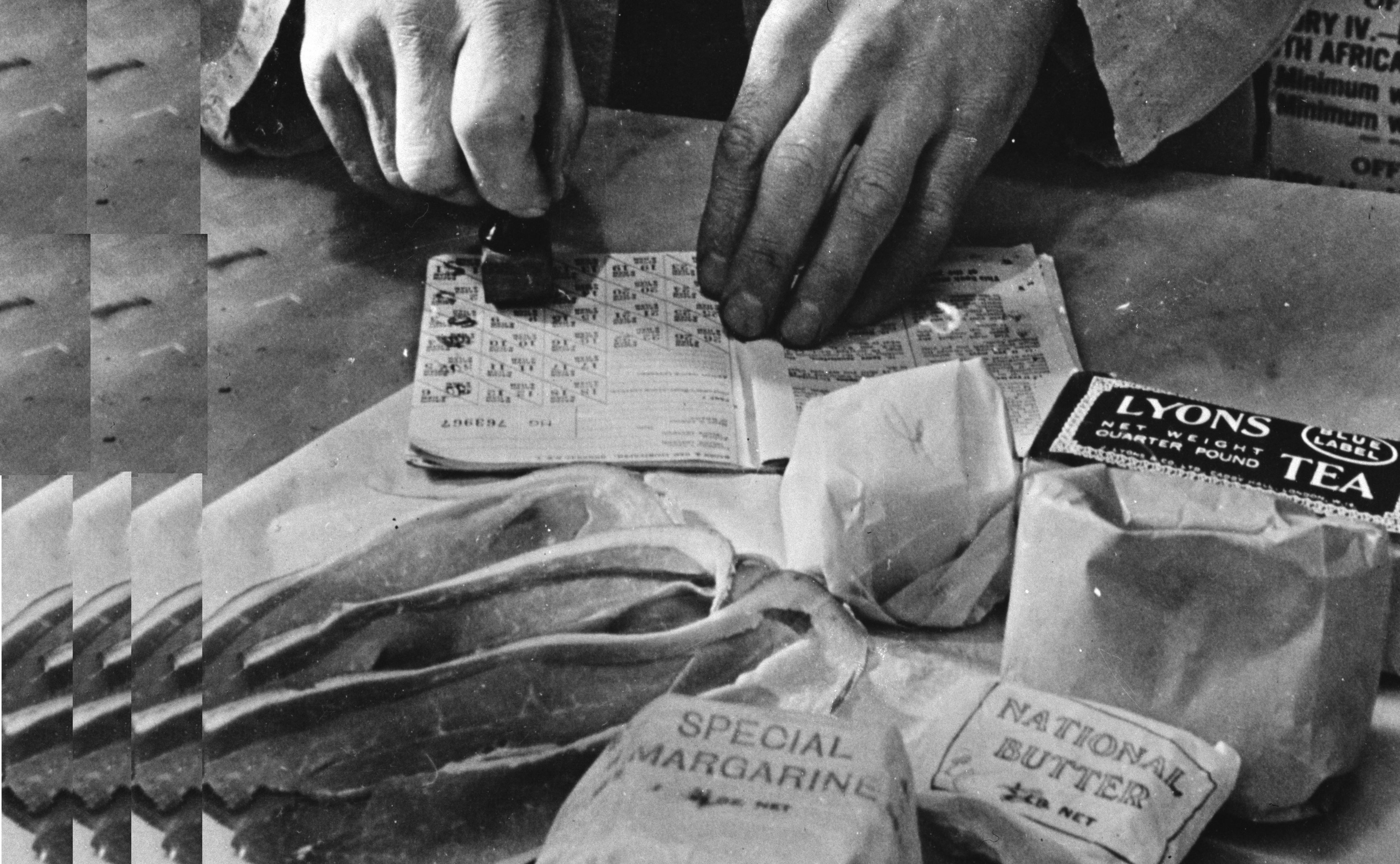

Lord Woolton, Minister for Food, used these results to develop his wartime food rationing policy, which included special measures to safeguard the health of mothers and children.

Rowett research was also influential when it came to maximising food production and Orr’s research, together with that of another senior Rowett researcher, David Lubbock was published in 1940 in ‘Feeding the people in war-time’.

Orr also joined a committee advising the Government on food policy and in 1941 became the first president of the Nutrition Society.

Despite the acute food shortages, Orr's research and Woolton's policies meant that the women and children of the poorer classes were healthier at the end of the war than at the beginning.

A Nobel Prize for peace

During the final years of the war Orr, now Sir John having been knighted for services to agriculture in 1935, became well known as a broadcaster and contributed to several publications which looked forward to post-war Britain.

When the peace agreement was signed he retired from the Rowett and briefly served as an independent MP for the Scottish Universities before resigning the position in 1946 to concentrate on his nutrition advocacy work.

He had been invited to attend a conference in Quebec in late 1945 to establish the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). His invitation to join the British delegation was made at the last minute, the British Government having tired of Orr's prickly independence, and he was permitted to attend only as an observer - not to speak.

Despite this, and the British delegation voting against him, Orr was overwhelmingly elected as the first Director general of the FAO during the conference, a post he held until 1948.

Once in post, Orr immediately set-up a temporary food-sharing organisation to alleviate the predicted shortages of the winter of 1946-47.

Encouraged by this success, Orr decided to push for a powerful, international 'World Food Board'.

Unfortunately the pace at which Orr worked baffled and disturbed the British civil servants. However, he thought it important to work quickly as he sensed that the opportunity for international cooperation was fading.

The World Food Plan was discussed at a meeting in Copenhagen and was supported by the USA delegation. Orr believed that he was on track to establishing a World Food Board.

But the British Government was opposed to Orr's plan and considered it to be impractical with serious financial implications for the UK. At a conference in Geneva, the USA delegation was persuaded to withdraw its support, and at the final vote Orr's plan was rejected.

With his plan defeated, Orr resigned from the FAO and returned to his farm in Angus a disappointed man.

Despite this defeat, and the number of subsequent attempts, Orr's plan is acknowledged as the closest to international cooperation in food sharing ever achieved.

At the end of the 1940s Orr's achievements were formally recognised. In 1949 he became a Freeman of the City of Aberdeen and was elevated to the peerage as Baron Boyd Orr of Brechin Mearns in the County of Angus.

Later that year he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize - his Nobel Prize Lecture was 'Science, Politics and Peace'. He donated the prize money to the National Peace Council and other similar organisations.

Orr took up many Directorships and was a member of 'The British Council for the Promotion of International Trade', which was considered to be a cover for 'fellow travellers' or communist sympathisers, but its aims were in line with Orr's views on world trade and peace.

He travelled widely in Europe and was an adviser on agricultural affairs to both the Indian and Pakistani governments. He was welcomed in both the USSR and China. Lady Orr was his constant companion as they met many international statesmen.

In 1953 his book `The White Man's Dilemma', which is published in many languages, set out his views on the concepts of a 'World Food Board' and World Government and he campaigned for these ideals to the end of his life.

By 1958 Orr had received honorary degrees from 12 universities in the UK and abroad, and had been awarded many medals and marks of distinction.

His last public engagement came in 1970 when he opened a large extension to the Rowett's laboratory facilities.

Orr died on 25 June 1971 at his home in Angus.

John Boyd Orr was a pioneer and visionary who highlighted the need for unity between agricultural production, food and nutrition to improve human health, and the parallel need for government, industry and science to work together in the public interest.

His work reflects why the Rowett has endured the test of time and will now celebrate 100 years of international research activity. The research undertaken here fundamentally altered the way people thought about food and health.

Understanding how nutrition influences health is central to addressing the problems many societies face today in regard to obesity, sustainability and food safety, and in this respect the Rowett continues to push the boundaries in our understanding of health and nutrition.”

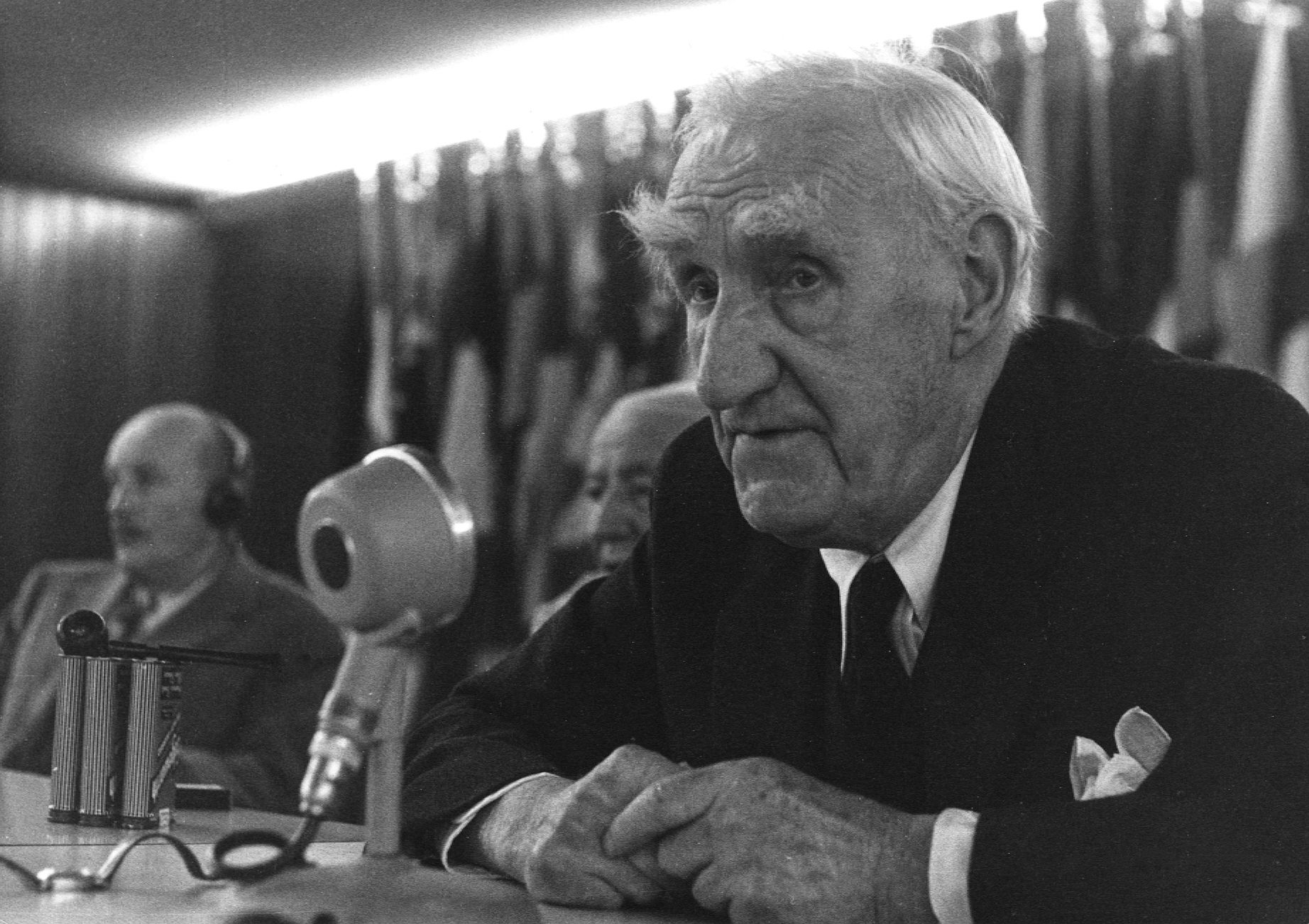

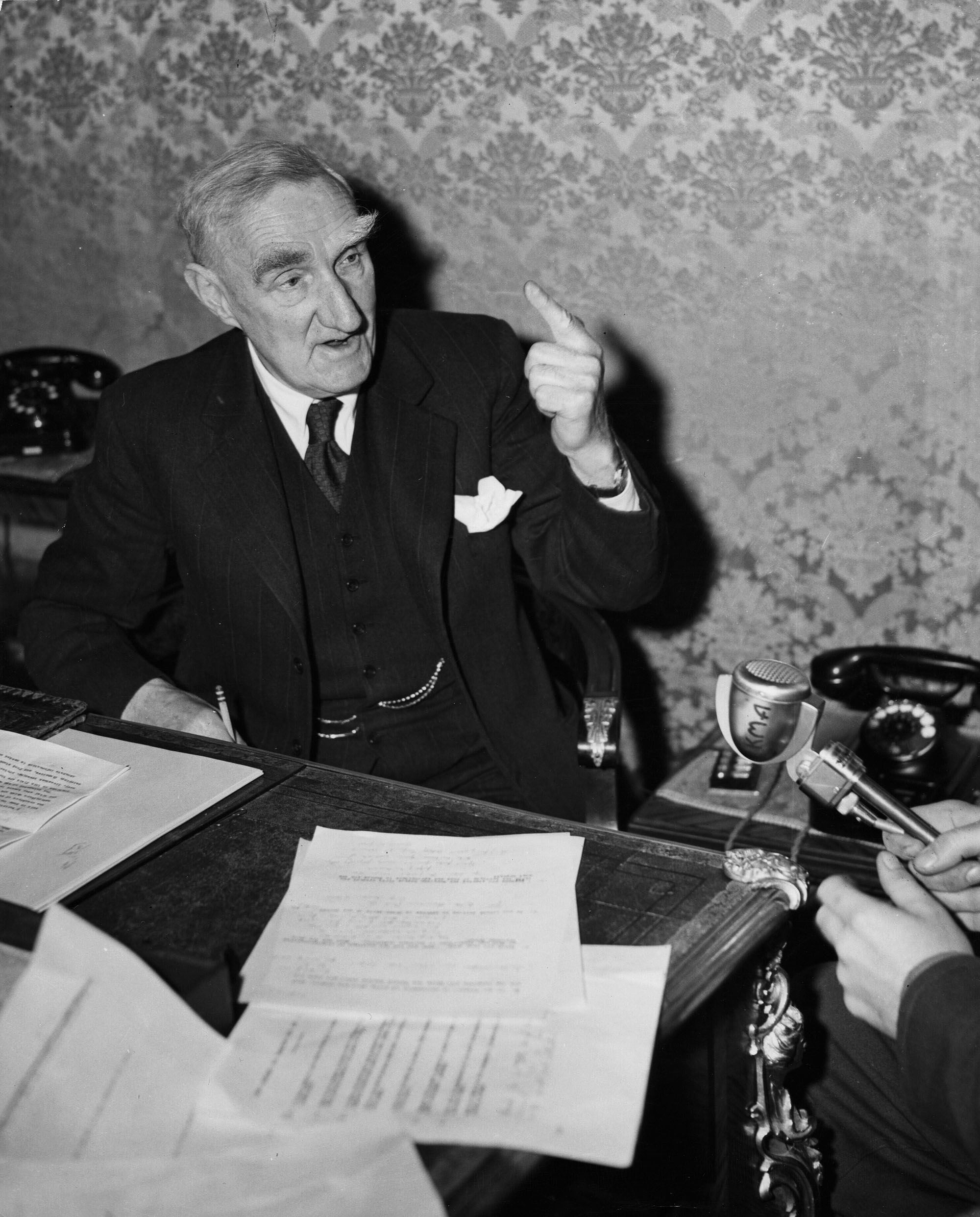

An animated Johd Boyd Orr talking to journalists

An animated Johd Boyd Orr talking to journalists

Images of John Boyd Orr in later life/ speaking to the media courtesy of the FAO © FAO photo

Image of a deprived area of Glasgow captured by Thomas Annan shortly before Boyd Orr began work as a teacher for the authority (courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland)

Images of the Sherwood Forresters courtesy of the National Army Museum

With thanks to Dr David Watts of the Rowett Institute for assistance with historical research

* Lord Boyd Orr (1966) As I Recall, published by Macgibbon and Kee

** H.D. Kay (1972) ‘John Boyd Orr, Baron Boyd Orr of Brechin Mearns, 1880-1971’, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Volume 18, pp. 43-81.