New findings and research from recent Rhynie archaeological digs, shed light on what happened back in 500AD on a knoll at the foot of Tap o'North hill. Article by Lisa Collinson - published in the Leopard magazine.

A bright midwinter morning, 500 AD, Rhynie, Aberdeenshire. Here, on a knoll at the foot of Tap o'Noth hill, inside a fortified enclosure surrounded by a huge wooden wall, a masked man stands, tensed, feet planted wide under a thick apron, axe-hammer poised, ready to fell the cow stamping and twisting in front of him. As the cow snorts and tosses her enormous head, her breath plumes out into the freezing air. Suddenly, she lets out a terrifying bellow, and lunges forward.

As strange as it may seem, new research from the University of Aberdeen suggests that at least some of this might really have happened.

The work is the foundation for the wonderful illustration by Alice Watterson, on which my opening description is based. But how much of it did happen - and why? And - trickiest of all to answer - what would the people present have thought and felt about animals killed in this way, as they watchedand heard them meet their grisly fates?

For centuries, cattle have been at the heart of the culture of North-east Scotland,sharing the land with its people, and giving them food, shelter, warmth, power and pleasure. This situation probably goes back at least 6000 years, with the precise relationships between cattle and people shifting subtly from time to time, place to place and even individual to individual.

Recently, the work of Fraserburgh-born Dr Gordon Noble, a senior lecturer in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen, has suggested that, as recently as around 500 AD, cattle may have been ritually killed at Rhynie: ‘Place of a Great King’, according to its Pictish name, painstakingly decoded by place-name expert Dr Simon Taylor, of the University of Glasgow.

The key to Gordon’s theory is a tiny iron pin his team found during a dig at the site, in 2012. “I clearly remember the moment it was found,” says Gordon, as we sit chatting in his cosy office in Old Aberdeen. “It was a sunny day in July a couple of years ago, and I was standing talking to two other archaeologists when I suddenly saw one of the student diggers, Zygimantas Tarvydas, bounding towards me, holding something in his hand. The second he showed it tome I felt incredibly excited; my gut instinct was that it was really special - maybe some kind of Early Medieval treasure. But my next instinct was to pull back, tell myself to calm down, look at it properly and try to work out what exactly we had here. Was it a modern door latch, for example? But actually, on this occasion, my gut instinct was right. What Zygimantas had found really was very special indeed.”

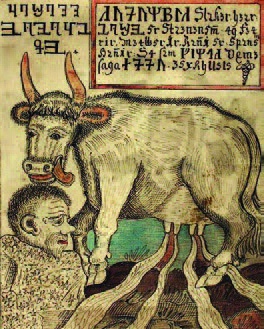

Certainly, the pin is a gorgeous object, with a slender handle and an elegantly curling ‘tail’. More than that, however, it seems to mirror, in miniature, a full-size axe pictured on one of the North-east’s most amazing cultural treasures: the famous Pictish ‘Rhynie Man’ Symbol Stone, originally found at Rhynie, and now housed in Aberdeenshire City Council’s offices, at Woodhill House, Aberdeen.

If you look closely at Rhynie Man, you’ll see not only astonishing pointed teeth (perhaps painted on a mask), but also a sturdy-looking garment covering the lower half of his body, which I’ve cheekily suggested could be a thick apron. The reason for this is that Rhynie Man’s axe, in common with the miniature axe found by Gordon’s team, looks very like an object, known as an ‘axe-hammer’, which was found at the Anglo-Saxon royal site of Sutton Hoo, and has been interpreted as a possible tool of cattle sacrifice, closely connected with kingship. This means there’s a good chance, at least, that Rhynie Man was himself depicted carrying an axehammer, likewise intended for ritual animalkilling at this more northerly ‘Place of a Great King’. What’s more, if later medieval Icelandic evidence is anything to go by, animal killing such as this would have been carried out in such a way as to make it as dramatic and bloody as possible.

We’ll probably never know for certain, but, based on Gordon’s findings, it seems to me pretty likely that such killing was indeed carried out at Rhynie, and that it was bloody, slippery and potentially dangerous. Under these circumstances, were I Rhynie Man, a strong apron would have been the very least protection I’d have wanted before raising my axe...

Apron or not, we can see Rhynie Man is fully clothed, as we’d expect of any Pictish person. Good coverage would, of course, have been especially important if the ritual we’ve imagined took place in midwinter, as I’ve suggested. On the other hand, we could just as easily imagine ritual animalkilling and feasting being carried out at other times of year: for example, around the beginning of November, when animals were slaughtered in the later Middle Ages, or in connection with a local gathering, in spring or summer, as at Hofstaðir in Iceland, around 1000 AD. There, the cattle skulls were probably hung on display for the feasting season, and possibly taken out at the same time each year, along with the next crop of fresh skulls.

Sadly, it’s impossible for now to say whether or not this kind of display took place at Rhynie itself; as many Leopard readers will know, we have very few written sources for Pictland, even from outside

the region, and unburnt bone material is extremely scarce, due to our acidic soil - although it’s worth mentioning, as an aside, that this didn’t stop Gordon from finding the bones of a woman in a cist grave roughly the same age as the Rhynie Man stone, at the very same site!

If understanding how the people who used the site at Rhynie are likely to have treated any animal remains is challenging, understanding how they might have thought and felt about living cattle is equally tricky - for very similar reasons. One set of clues is probably provided by Pictish symbol stones from Burghead (Moray), showing bulls, and perhaps hinting at a bull cult there.

Otherwise, it may be that our best hope lies in looking at evidence from other parts of the British Isles and the Nordic countries, including Iceland, as well as further afield.

With this in mind, participants in a separate project co-led by Gordon -‘Pathways to Power: The Rise of the Early Kingdoms of the North’ - including me, will be spending time over the next few months trying to unpick some of this outside evidence, along with experts from other Aberdeen projects and other universities, all of whom are interested in finding out more about how people and animals have interacted over time, especially in the North. Since my own research focuses on written

sources from medieval Scandinavia, I’ll be starting with the juiciest texts from the Nordic countries. One of the oldest of these (around 400 years younger than the Rhynie evidence) is a Norwegian poem, Ynglingatal, which sketches the lives of Scandinavian kings - some legendary - and grimly emphasises their spectacular deaths, one ofwhich results from goring by a bull. This is important, because it shows that in Early Medieval Norway, just as in Early Medieval Rhynie, cattle were probably linked in people’s minds to both death and kingship -in certain situations, at least.

At the other end of the spectrum, in later folklore (recorded around 750 years after Rhynie Man was carved, but potentially older in origin) there seems to have been a strong connection between cattle, birth and fertility. This comes out in the Icelandic tale of the primordial cow,

favourite collection of Nordic cattle sources: lists of poetic names, which offer rare insights into the ideas and stories people linked to these beasts in the Middle Ages, here in Northern Europe. Many refer to the ways cattle looked and sounded: ‘Dappled’, ‘Droaner’ and ‘Bellower’, for example, but others gesture towards their economic value (‘Wealth’ and ‘Inheritance’), and names such as ‘Smith’ and ‘Spark’ may hint at use of their bones in metal-working. A number of names are shared with mythological figures, such as ‘Freyr’, as was common when naming people and things in Viking verse, but one of the most interesting looks very like the Old Gaelic word for ‘bull’tarb)...and explaining why it’s listed here is doubtless going to take prolonged headscratching! How often names such as these could have been attached to real animals as well as beasts only ever mentioned in the highly-stylised medium of Viking verse, is an open question - but one worth considering, I believe, if we’re serious about looking at animal-human relations in the North from every possible angle available to us.

Perhaps you have some interesting thoughts of your own to share on cattle in the North? If so, it would be great to read them on the Leopard Letters page!

Article by Lisa Collinson postdoctoral research fellow, working on the project Pathways to Power: The Rise of the Early Kingdoms of the North.

With thanks to the Leopard magazine December 2014 to January 2015 issue who welcome readers' letters, stories, suggestions, photos and comments.

Notes for Editors

Email: editor@leopardmag.co.ukOr write to Leopard Magazine24 Cairnaquheen Gardens Aberdeen AB15 5HJ

For enquiries about subscriptionsemail subs@leopardmag.co.uk

For enquiries about advertising in Leopard contactWalter Miller tel: 01466 730776email leopardmag@talktalk.net

Leopard magazine is published by University of AberdeenKing’s CollegeAberdeen AB24 3FXTel: +44 (0)1224 272014communications@abdn.ac.ukwww.abdn.ac.uk