Marten Hunting near Surinda

An Evenk hunter with his tethered hunting dog and lead reindeer returning from a hunt.

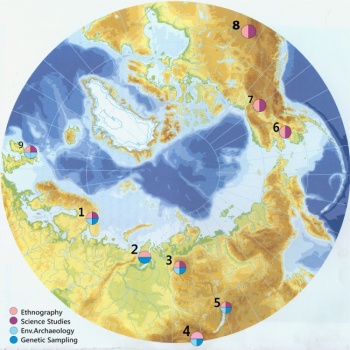

Stories of how the lives of people and of animals interweave can help us solve fundamental questions about the environment. Through fieldwork in seven fieldsites across the Arctic from the Russian Federation, to Fennoscandia, Canada, and Alaska, we have worked to document a wide variety of relations between humans, animals and places where they live. Our focus was on 'domestication' - the skill of building relationships with entities outside of one's home.

Our research sites included reindeer herding camps, fish camps, evocative landscapes, archives, as well as biotechnological laboratories. Aside from challenging the idea that domestication is always dominating, we developed a language to express how communities of people and of animals invigorate life in Northern places.

Among the enduring themes of circumpolar ethnography are the themes of personhood where landscape forms or non-human animals are ascribed agency; the phenomena of shamanism where knowledgeable specialists move powerful forces from one animate agent to another; and the discipline of 'knowing' where individuals work out rules of thumb for understanding their world.

The members of this project have concentrated on how agency and sentience are ascribed to animals, peoples and to landscape. Ethnographic work was applied in salmon hatcheries and pedigree reindeer stations to capture how technicians learn to know a new or modified species.

We were interested in documenting local, hear-say categories of behaviour ('agitated', 'hungry'), emotion ('confused', 'angry'), intention ('ready-to-bolt', 'homebound'), as well as the unique spatial classifiers that people associate with the possibility of human-animal co-presence.

Our work on 'emplacing' these relationships provided an important effort to consolidating recent work on landscape ethnoecology, the 'built environment' and niche construction.

Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted in Alaska, Canada, Fennoscandia, and the Russian Federation.

An important part of our work was devoted to understanding what qualities laboratory scientists look for when they 'design' a domestic salmon, or the skills that a reindeer herder might use to attract reindeer back to a camp after they have 'gone wild'.

We have also investigated the unique and often controversial relationships created when governments seek to manage nature. Science studies were conducted in Alaska, Fennoscandia, and the Russian Federation.

When people and animals live together over a long time in a specific place, the land responds to their presence by hosting new plant communities which act as 'signatures' to this relationship.

Environmental archaeology was conducted in Fennoscandia and Russian Federation.

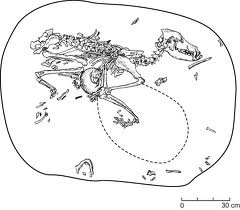

Further, the history of relationships between humans and animals can often be read from animal bodies, with relationships of care or of exploitation being carved into skeletons. Members of the project team experimented with identifying stress-markers of harnessing or signs of healing within the skeletons of reindeer and dogs. Genetical research was conducted primarily in the Russian Federation with domestic reindeer. Samples will be required, for example, from shedded antlers. Osteological research was conducted predominantly in the Russian Federation and also in museums in Canada.

Biologists and ethnographers have recognized these three sets of animals as 'key' species across the North, and much attention has been spent on which species was domesticated 'first' in time, but there has been little work on how they negotiate their co-existence

Dogs are perhaps the most well-known domestic species thought to be the first animal ever domesticated and the focus of much popular and scientific literature today. Ethnographically, as in genetic studies, they have been taken for granted. The project therefore performed fundamental work on documenting dog breeds and how dogs co-produce domestic relations together with human persons.

Standard research protocols document place (GPS co-ordinates) species, and sometimes type (domestic, wild). This research is primarily based on, and continues to be, in the Russian Federation.

The goal of this programme was to gather as much information about the life of a specific animal as possible - as if that animal were a person - and to link that information to genetic and/or bone samples in specific examples (e.g. domestic reindeer and dog skeletons in Russian Federation, salmon and domestic reindeer in Fennoscandia, and dog skeletons in Canadian museums).

The Russian Federation questionnaire is open-ended. Please pay attention to local terms to describe animals - even if those terms may not find a translation in a scientific term. Please avoid using scientific terms such as 'tundra reindeer', 'forest reindeer', 'wild reindeer' unless these are used by the person whom you are speaking with.

The questionnaire for ethnographic fieldwork focuses more on the interspecies and the role that dogs have played and continue to play in the Arctic. The questions are concerned with the life-histories from dogs and are primarily based on the stories of indigenous peoples.

The fieldwork investigated how populations and/or animals are placed within certain settings, and become the focus of scientific or management projects as well as the life projects of local residents.

Our team have documented relationships in particular field sites rather than focussing on one people or one species.

Post-doctoral fellow Dr. Anna-Kaisa Salmi concentrates on the archaeology of reindeer domestication and changing human-reindeer relationships in Medieval and Early Modern Fennoscandia. Through the zooarchaeological analysis and stable isotope analysis of reindeer bone remains from archaeological sites, as well as through reconstruction of reindeer's physical activity she explored the interactions between the Sámi and reindeer in the past, concentrating especially on reindeer feeding and harness use.

The associated scholars Gro Ween and Prof. Marianne Lien have conducted fieldwork among local salmon fishermen as well as with industrial salmon farmers in the Norwegian region of Finnmark. If dogs are commonly said to be one of the first domesticates, salmon are one of the most recent. Their status as a relatively domestic or 'alien' species that can easily break free of their aquariums has sparked controversy as environmental activists and local fishermen discuss natural vs farmed types of salmon.

Domesticated reindeer have been a signature northern species in this region historically as today. Together with associated scholar Knut Røed, Prof. David Anderson has investigated the physical and biological qualities of domesticated reindeer in terms of their mitrochondrial geography and nuclear markers of coat colour. These data are showing interesting contrasts with Northern Russian and Siberian samples suggesting new stories of the domestication of reindeer in this region.

Picture No ERM1729:47 - ERM (Eesti Rahva Muuseum) acrhive in Tartu, Estonia

A large team of researchers within Arctic Domus have investigated human-animal relationships on the peninsula. Prof Konstantin Klokov , a regional fieldworker from St. Petersburg State University, documented the different ways that Nenets dogs and reindeer are trained to associate with mobile human camps. Similarly, Dr. Dmitry Arzyutov , was investigating the status of companion dogs (and cats) among mobile reindeer herding families.

The indigenous peoples have domesticated some of these 'wild' reindeer whilst also hunting the large herd. This hybridisation of 'wild' and 'tame' reindeer have been the most vivid example in this region. Dogs, furthermore, have been an important companion of the reindeer herders and hunters.

The literature and research, however, have not yet given significant attention to the dogs nor the complexitity of the changing patterns of the indigenous peoples.

Field research in the region began in 2014 with the fieldwork in Khatanga district, Taimyr, of regional fieldworker Dr. Vladmiir Davydov . Prof. David Anderson in colloboration with Knut Røed of the Norwegian Veterinary College and Marina Kholodova of the Severtsov Institute of Ecology in Moscow, who are studying the genetic markers of wild and domestic reindeer in the region.

The region forms the fieldsite of the doctoral candidate Alex Oehler who began his fieldwork in the Soyot district of Buriatiia in 2013. Fieldworker Prof. Konstantin Klokov has made an initial survey of the district inhabited by Tofalar hunters within Irkutsk province. In 2014 and 2015 we extended the ethnographic and historical fieldwork to include pollen core analysis of specific sites of long-term reindeer and horse pastoralism.

Arctic Domus had a number of ongoing-projects in the region. In the North Baikal district of Buriatiia, regional fieldworker Prof. Artur Kharinskii lead a team investigating the long-term pollen signatures left by historic and contemporary reindeer corrals.

This research provides an important context of comparison to similar research being undertaking on the Iamal peninsula. Regional fieldworker Dr Vladimir Davydov wrote an ethnographic description of how both domestic and wild reindeer are tamed to differing degrees with his research in North Baikal and Kalar Districts.

Prof. David Anderson also conducted fieldwork in both locations to develop an account of 'architectures of domestication'.

At the same time there is a discussion between up and down Yukon River about management policies and harvesting fish. Our research elaborates on the relationships between fisheries, 'wild' populations, fish science, management policies, and the interplay between fish, dogs, and indigenous peoples.

Arctic Domus associated scholar Dr. Gro Ween conducted fieldwork in the mouth of the Yukon River, in the village of St Marys - a community of 600 people not far from where the Andreafski leaves the Yukon. This land is the home of the Central Alaskan Yupik people, the most numerous of Alaskan native peoples. Yupik people in this area have always moved between camps, fishing in the summer, hunting and trapping in the winter and continue to do so. In this part of the Yukon River, the landscape is a mixture of rivers, creeks, wetlands, with boreal forests and some mountains. Pacific salmon, and most importantly, King salmon have always been of vital importance to their diet. Animals were hunted and trapped both by women and men, both for food and clothing and previous time periods also for sale.

Arctic Domus team-members Dr Peter Loovers and Dr Rob Wishart have conducted fieldwork in northern Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories with Gwich'in. In particular, they worked in the communities of Fort McPherson and Old Crow.

Arctic Domus team-members Dr Peter Loovers and Dr Rob Wishart have conducted fieldwork in northern Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories with Gwich'in. In particular, they worked in the communities of Fort McPherson and Old Crow.

The medium-size town of Fort McPherson lies along the Peel River which is a tributary of the Mackenzie River and is home to the Teetl'it Gwich'in. There are two shops with gas stations, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Health Clinic, School, Tourist Centre, Hamlet Office, Tribal Office, Government buildings etcetera. The smaller settlement of Old Crow lies across the mountains where the Crow River joins the Porcupine River, a tributary of the Yukon River, and is home to the Vuntut Gwich'in. Together with other Gwich'in communities scattered across northern Alaska and Canada they comprise the Gwich'in Nation.

The land is a mixture of rivers, creeks, wetlands, lakes, boreal forests, and mountains. The Porcupine Caribou herd is of a pivotal importance for the Gwich'in for their livelihood and identity. At the same time, a number of Gwich'in continue to trap furbearing animals whilst a large number of Gwich'in engage with fishing and picking berries. The Teetl'it Gwich'in primarily fish for whitefish, inconnu, loche, and in the past herring. The Vuntut Gwich'in primarily fish for whitefish and salmon.

During the first period of fieldwork (January-February 2013, May 2013- July 2013), Loovers investigated the relations between dogs, the Gwich'in, fish and caribou. Until the 1980s, the Teetl'it Gwich'in were using so-called 'working dogs' for transport and procurement of food and goods (e.g. through the trade in furs and meat).

The 'working dogs' were a hybrid of many breeds of dogs including huskies, German shepherds, and wolf-dog hybrids. Strength and endurance have been traits that were highly valued and a common saying is that “the dogs worked for us, and we worked for them”.

During interviews and spending time out on the land, it has become apparent that this aspect of working entailed fishing throughout the year for the dogs. A large quantity of herring and white fish were stored and processed in different ways to secure enough dog feed for the winter. At the same time, meat would be given to the dogs during successful hunting trips. Whilst the 'working dogs' had also been important in Old Crow, an early shift to 'racing dogs' occurred in the 1960's and 1970's. A number of Vuntut Gwich'in became famous regional dog mushers winning at Territorial and International competitions. Unlike the 'working dogs', the 'racing dogs' were smaller build and bred to be racing long distances. Salmon, rather than herring and white fish, was the main food source for the dogs in Old Crow.

During the same period Wishart conducted archival and ethnohistoric research investigating the role of fish and fishing in the establishment and fluorescence of the fur trade. Key to this research has been investigations of animal-human relationships but also economic models and practices of advances and provisions. In this research fish can be understood to be directly connected to the economics of hunting and trapping while at the same time forming a set of practices that are important for sociality and which are cherished by the Gwich'in themselves. It challenges the lack of attention that fish have had in the literature and helps in providing a historic background for Wishart's future ethnographic research plans in 2014.

Besides this, the research has also been interested in the concept of designing dogs, training and handling dogs, and the technology that dogs enabled (e.g. fishing technology and travel technology). Dog mushers or dog team owners have been speaking about the different ways of seasonal feeding to shape the dog as well as the crafting of dogs through breeding and training. At the same time, the Gwich'in speak of dogs as intelligent and sensitive with whom they establish mutual emotional relations.

The research, thus, goes beyond orthodox anthropological 'hunter-gatherer studies' and rather discusses the way aboriginal people relate with a wide variety of animals in particular ways whilst also investigating the relations between animals (e.g. dog and fish).

Regional fieldworker Dr. Clinton Westman conducted his research in the boreal forest region inhabited mainly by Cree and Metis people. The communities where he has ongoing research relations include Bigstone Cree Nation, Peerless-Trout First Nation, and Woodland Cree First Nation. These locations were first visited by missionaries and traders in the late 19th century but did not exist as permanent communities until the 1950s and later as people were larger dependant on the bush for their survival until the arrival of roads and industry in the 1970s.

Influential ethnographic studies of contemporary Cree people in the Canadian subarctic suggest that Cree relations with animals have focused on the ambivalence, alternately invoking categories such as friendship, love, pity, enmity, exchange, and deception to explain the dynamic between predator and prey, spirit and supplicant. Westman used this body of work to query ideas about human-animal relations; not only to search for ideas and practices that appear to fit on a continuum towards domestication, but also to consider the rapport between humans and animals in a spiritual, religious, or cosmological sense.

Shetland's location and climate are thought to have contributed to a wide variety of distinct plant and animal life with perhaps the best known being Shetland ponies. Small horses are thought to have lived in Shetland since the Bronze Age and today's breed are considered to be one of the oldest native horse breeds.