Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is used every day in tens of thousands of hospitals around the world, helping doctors to diagnose disease and monitor treatment. Almost 40 years ago, a team of scientists at Aberdeen University built the world’s first human-sized MRI scanner, and used it to perform the first-ever diagnostic MRI scan in August 1980. Now, a research team in the University’s School of Medicine, Medical Sciences & Nutrition is developing a brand new type of MRI machine, called “Fast Field-Cycling MRI” (FFC-MRI), and has recently begun trials of the new scanner on patients. It is hoped that the totally new information generated by this device will help doctors diagnose breast cancer and monitor treatment.

The familiar “doughnut” shape of an MRI scanner encloses a powerful magnet. In a typical hospital scanner the magnetic field is very strong (30,000 times stronger than the earth’s magnetic field), causing the magnetic hydrogen atoms in water molecules within the patient’s body to line up. When the scanner then sends a brief pulse of radiowaves into the patient, the hydrogen atoms absorb energy and start to rotate, in turn giving out a weak radio signals which are picked up and analysed using a computer to create highly-detailed pictures of the patient’s anatomy.

Medical physicists at Aberdeen University realised a decade ago that it might be possible to obtain extra diagnostic information that is hidden to “standard” MRI machines and this has led to them developing the FFC-MRI scanner. While a standard MRI machine operates at a constant magnetic field, an FFC-MRI scanner is able to change its magnetic field strength while the patient is being scanned. This is almost like having 100 different scanners in one machine, each with a different strength of magnetic field. It generates information on how the magnetic properties of tissues change with magnetic field and the idea is that this can be used as a new kind of “fingerprint” of disease.

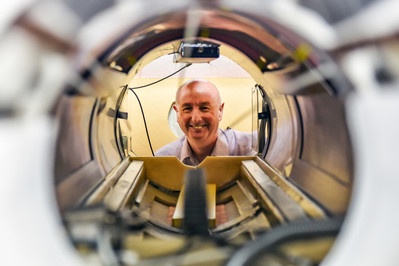

Using their latest prototype human-scale FFC-MRI scanner (unique in the world), the Aberdeen team of physicists, doctors, nurses and radiographers recently started imaging patients – the first ever to be scanned by this new technique. Initial results have shown that FFC-MRI is able to detect changes in brain tissue following ischaemic stroke; further studies are underway to image patients with a range of conditions. The team is particularly interested in using FFC-MRI to study breast cancer. Preparations are underway to allow FFC-MRI scans of the breast to be performed – initially in normal volunteers – and the first phase of modifications of the scanner to do this are almost complete. It is hoped that the FFC-MRI “fingerprint” will be useful in determining the grade of a patient’s tumour non-invasively, in order to help guide a patient’s treatment plan. Indeed, early laboratory results on small tissue samples have shown that the FFC signals are likely to be useful in this context and that FFC-MRI might also be able to assist surgeons in determining the precise margins of tumours, prior to surgery.

The collaboration of researchers at Aberdeen University with NHS staff in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary is resulting in Aberdeen once again leading the world in the development of scanning technology. Furthermore, the FFC-MRI project has received very significant funding (€6.6M) from the EU, with Aberdeen leading a consortium of nine partners in six countries, all working to improve the scanning technology. Perhaps one day FFC-MRI scanners will be found in all major hospitals!

Further information is available at www.abdn.ac.uk/research/ffc-mri/