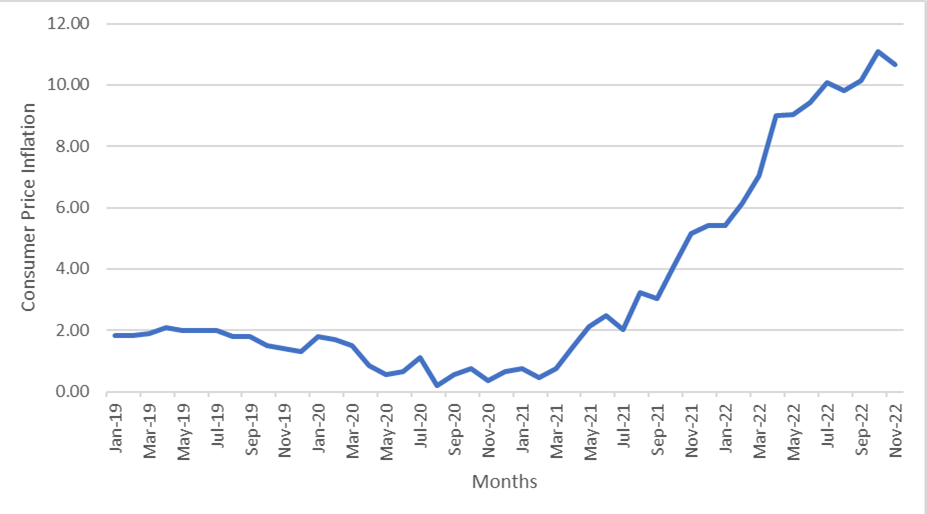

The disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic on food supply chains and the Russia invasion of Ukraine has implications for food prices in the UK. Food prices have continued to soar, especially for meat, eggs, and dairy, due to rising energy costs, costs of animal feed and transport. Figure 1 shows the evolution of overall consumer food price inflation from January 2019 to November 2022. Food prices have risen from 0.18 per cent in August 2020 to 10.66 per cent in November 2022; 8 and 16 per cent rise for fruit and vegetables, respectively (Office of National Statistics, 2022). This has implications for population diet, nutrition and health especially for the poorest of the poor.

Figure 1. Evolution of Food Price Inflation in the UK

Source: Own computation based on ONS dataset

In this article, we use modelling done using Kantar Worldpanel data for Scotland to show how consumers might react to this rising food prices and the consequent effect of eliminating retail promotions from foods high in fat, sugar, and salt (also known as discretionary foods) whilst promoting fruit and vegetables.

We begin the analysis by considering the impact of a 10 per cent[1] food price inflation on all food aggregates. We have held the budget and income constant to ensure that they do not offset the impact of the inflation[2]. Figure 2 shows the implications of this price rise for food purchases for the average consumer in Scotland. We see that price increase in the discretionary foods to be higher, ranging from 8.3 per cent for Biscuit to 11.1 per cent for Edible ice and ice-cream. However, they are also the most promoted food groups thus offsetting their actual price and demand. For instance, according to The Food Foundation (2021) 46 per cent of food and drinks advertisement goes on confectionery, sweet and savoury snacks and soft drinks whilst only 2.5 per cent goes to fruits and vegetables.

Purchases of fruits and vegetables are expected to fall by 10.2 and 9.8 per cent, respectively. The reduction is very significant and could offset the goal of government to increase population consumption of 400 grams of fruits and vegetables a day[3]. For the remaining foods, a 10 per cent price inflation could lead to about 11.2 per cent reduction in the purchases of alcoholic beverages to about 8.3 per cent reduction in grains.

Figure 3. Implications of a 10% price inflation on all foods types

Source: Own estimation based on Kantar Worldpanel data,

In this section, we show how food price promotions could be used to compensate consumers for the price inflation and stimulate them towards healthier food options. Figure 3 shows the implications of eliminating promotions on all food aggregates excluding fruit and vegetables (where their promotion has been increased by 20 per cent). The estimation considers the interactions between the different food groups, holding prices constant. The simulation results show that the purchases of fruit will increase by 5 per cent whilst vegetables purchases will increase by 3 per cent. Purchases for the remaining food groups will reduce marginally except for Dairy products, Meat and fish, and fats and eggs. We therefore expect that a shift from the promotion of unhealthy foods towards healthy foods will reduce the demand for unhealthy foods but increase demand for healthier foods options. Specifically, the demand for all types of discretionary foods (first seven food aggregates on the left-hand-side of the graph) will fall. Hence, promotions of fruit and vegetables could be used by food retailers as a means to compensate consumers for the current food price inflation and also stimulate the consumption of more fruits and vegetables.

Figure 2. Increasing promotion by 20 per cent on fruit and veg. whilst restricting promotion on all other foods

Source: Own estimation based on Kantar Worldpanel data.

Retail promotions or supermarket deals have larger impact on the purchases of discretionary foods than all other food groups. Our model shows that shifting promotions from all foods towards fruit and vegetables will have a small impact on the purchases of those foods but an appreciable impact on fruit and vegetable purchases. Food price inflation is expected to reduce the demand for unhealthy foods more than healthier food options if they are not promoted.

This research was funded by the Scottish Government RESAS 2022-27 budget.

[1] This figure ranges from 4 to 29 per cent in the ONS dataset for November

[2] We are aware of labour agitations to increase salaries. Any increases in disposable income will offset the impact of the food price inflation

[3] https://www.foodstandards.gov.scot/downloads/Situation_report_-_the_Scottish_diet_-_it_needs_to_change_-_2018_update_FINAL.pdf