When we interact with other people, we often find it relatively easy to understand the meaning behind their behaviour, and the reasons for why they act how they do often come to us unbidden. We seem to just know why our child drags us towards a shop window, why our friend steers clear of the spider, or why our partner hands us a drink after a workout.

But how does our brain do that? Figuring out the reason for other people’s behaviour is no easy feat. There is no fixed meaning to any behaviour. Think about the many things a simple smile can convey, for example. The brain can therefore not simply “look up”, like in a dictionary, what each behaviour may mean. Moreover, often people do things based on what they think about a situation rather than on objective reality. This means we often do not even know what information other people base their actions on, making the puzzle even more difficult.

Our research assumes that the brain uses a strategy of prediction to solve this puzzle. The idea is that our brain creates a mental model of everything we know about a situation (e.g., which objects it contains) and the persons within it (what they want, what they think). From this mental model, it then makes predictions about how the person would react, if it is correct about them. If this were the case, we would not need to figure out the meaning of each action as we see it. Instead, we would only need to check whether it roughly aligns with what we think about the person already. If it matches, we know our mental model of them is roughly correct. Only if it does not match, do we need to go back and revise our mental model until we find a better reason for why they act the way they do.

Innovative research led by Prof Patric Bach demonstrated that our perception of other people’s behaviour is indeed driven by such predictions. It relied on the simple assumption that, if we understand other’s behaviour in light of our prior expectations, then we should find evidence of some sort of confirmation bias. In other words, we should interpret others’ behaviour in line with our expectations rather than objective reality.

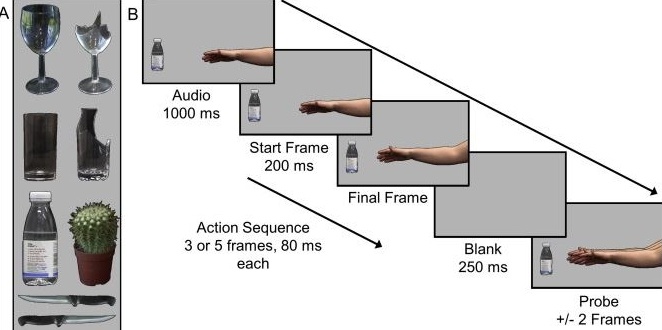

In our experiments, we therefore first give people information about a person (e.g., that they “want” some object but dislike others) and then asked them to trace (e.g., on a touch screen, or with a mouse) the actions they saw them do. The results consistently show that people perceive the same behaviour slightly differently depending on the expectations they had about it. For example, it seemed that a person reached closer to objects they said they want, but further away from any obstacles – but only if it is a person but not a ball that cannot have such goals. Moreover, people seem form such expectations even when an action is underway: if we see a hand open wide, it may look as if it reaches towards a large object, but to a smaller object if the fingers make a small pincer grip, even if in reality there is no such difference. Even quite remote information about other people’s goals (that they want to fix a creaky chair) induces such changes to perception, causing us to expect them to reach for DIY tools instead of other objects, for example.

These findings provided key evidence that people perceive other people’s behaviour in light of their prior expectations. Our current research now tries to find out how detailed the mental models are we create of other people (e.g., do they model another’s false belief, for example, where an object is that the person cannot see), do the same changes to perception happen when we see another person’s facial expressions (e.g., does a face look happier when we expect them to be happy), and what the brain mechanisms underlying these processes are, using EEG and fMRI.

Link to press coverage that this work has received.

Visit the project website.

Find out about the School of Psychology researcher behind it: