Magnetic Resonance Imaging - or MRI scanning - is in the bones of the University of Aberdeen’s Biomedical Physics department. It is one of the great ‘good news’ stories for the University and for the city of Aberdeen. MRI was developed here and emanated across the world, saving millions of lives. The University of Aberdeen has continued to be a centre of excellence in the field and is now driving the next generation of the technology - Fast Field-Cycling MRI.

MRI development should be a point of pride for the city. The problem is that experimental biophysics is just so bloody hard to understand for the wider public. What happens is a group of people go into tiny-windowed offices, beaver away, and every 20 years some world-changing piece of equipment emerges as a result of their labour, accompanied by a flurry of dense papers that appear in scientific journals. It’s a very difficult process to empathise with, not least because the physics behind it is infernally complex.

In late 2018 Grampian Hospital Arts Trust commissioned two exhibitions and a publication that aim to bridge two moments in the history of MRI innovation at the University of Aberdeen. The exhibitions, called From Where Do We See and Immobile Choreography by Dr Silvia Casini and artist Beverley Hood, respectively, approach MRI in Aberdeen from different angles and look at different time periods. They look to humanise the story of the science of MRI and remediate it for new audiences. Both exhibitions opened in April and run until June 16, they are accessible to the public 24 hours a day. The publication is being launched this Friday, May 24, in The Suttie Arts space, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

The three usually discrete worlds of art, science and the humanities have been brought together for the project.

The humanities are represented by Dr Silvia Casini of the University of Aberdeen’s School of Language, Literature, Music and Visual Culture. Dr Casini spent a year embedded in the team currently developing Fast Field-Cycling MRI. She has outstanding academic expertise in the aesthetics of MRI, and used her time with the team to better understand the world of ‘Night Science’.

“Night Science, as the French biologist François Jacob defined it, is the often obscured background to scientific development and innovation,” Dr Casini explains. “It encompasses the everyday laboratory activities of the scientists. It is the secret activities, struggles and hands-on labour that contribute to the final result of the experiment but that are often invisible in the published results.”

Dr Casini adds: “The purpose of the exhibition is to add the narratives that are not yet represented. That includes the craftsmanship element and aesthetic judgments that accompany scientific discovery, but rarely become part of the official history of an invention. Craftsmanship is one of the Aberdonian contributions to the MRI development. There is a perception of science as being a polished thing, so one of our aims was to bring the trial-and-error element, the struggle element, back into the public understanding.”

Her exhibit in The Small Gallery in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary contains, for example, the drawings, sketches and rough notes of some of the team working on MRI. The sketches, in particular, show scientists working through their thoughts through drawing and sketches, much in the manner of an artist. This makes the struggle of the scientists more visible and relatable to the wider public.

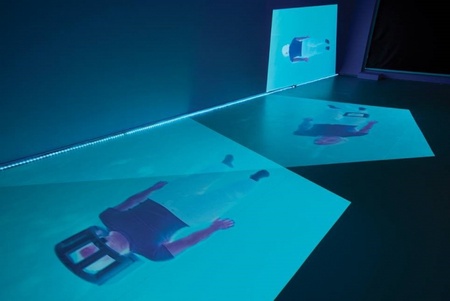

Beverley Hood created the exhibit that now graces The Suttie Arts Space. Hood is an Edinburgh-based artist who responded to a call for new work responding to MRI. As part of her investigation of the MRI process, Hood submitted herself both to traditional MRI and to the newly developed Fast Field-Cycling MRI scans, becoming both artist and subject of experiment.

Hood’s work focuses particularly on the Fast Field-Cycling development of MRI. The new type of scanner developed at Aberdeen changes the field strength of the magnet in order to obtain multiple images of the subject. It utilises a phenomenon called ‘T1 relaxation time’, which is a measurement of how particles in the body react to magnetism. Simply put, a magnetic field is applied to disrupt hydrogen molecules, then it is removed. The time it takes for the hydrogen particles to ‘relax’ back to their previous state is measured, giving vital diagnostic data.

Hood’s striking audiovisual installation, which has a choreographed dancer moving whilst contained within the scanner coil, responds to this phenomenon of relaxation, as well as the distinct sound differences between standard MRI and the new FFC MRI scanner.

Dr Casini helped mediate between the exhibitions and the scientific group in part through long-term exposure to the team’s work. She was able to find elements of the ‘night science’ the team were conducting that is relatable and comprehensible to a wider audience.

The project also has a published element: a catalogue with contributions from Professor David Lurie, head of the FFC MRI development at Foresterhill, from Beverley Hood and from Dr Silvia Casini. Dr Casini said, “the publication [in part] argues the importance of conducting laboratory ethnography and archival research, of not forgetting the historical element behind every new technology. It argues in favour of opening up the black box of technology, understanding it from the inside, its history, its way of seeing. As with the paired exhibitions the catalogue contains all 3 elements of science, art and humanity research”.

The publication launch this Friday is accompanied with a roundtable discussion. Beverley Hood, Dr Leeanne Bodkin – clinical lecturer and coordinator of medical humanities, Dr Silvia Casini, Dr Lionel Broche of the FFC MRI project, Neil Curtis – Head of Museums & Special Collections will approach the subject of MRI from the perspectives of their specialisms.