Eyewitness accounts of the bloody 17th century rebellion that drew the battle lines for Ireland’s Catholic-Protestant divide – and claimed the lives of thousands of Scottish Protestants – are to be made publicly available for the first time.

A team of scholars, led by researchers from the University of Aberdeen, will mark Tuesday's (October 23) anniversary of the 1641 Irish Catholic uprising in Ulster with the launch of a project to transcribe and digitise thousands of testimonies by those who lived through the alleged "massacres" 366 years ago.

The huge stockpile of evidence, housed in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, has never been comprehensively analysed, but could hold the key to providing an accurate account of the brutal events that triggered centuries of sectarian divide.

What actually occurred is the subject of one of the bitterest controversies in Irish history. Some argue that an attempted bloodless rebellion by Catholics quickly spiralled out of control. Others claim that thousands of Scottish and English Protestants were deliberately massacred.

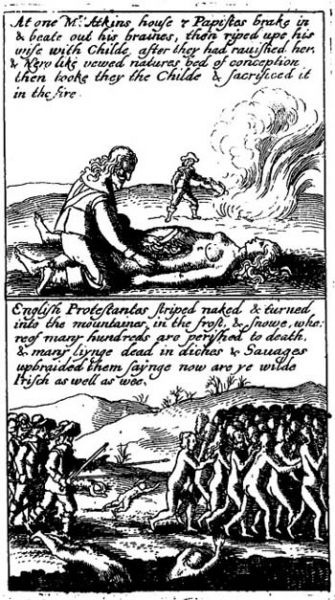

The decade of savage warfare that followed is so deeply etched into the national consciousness that images of the supposed "massacre" are still used on banners by the Orange Order to this day.

But the true course of events has never been fully understood. By making the 19,000 pages of depositions and other documents widely available, the project team – which also includes researchers from Trinity College, Dublin and Cambridge University – hopes to shed light on one of the darkest moments in Ireland's troubled past.

The three-year, Aberdeen-devised project is the most ambitious joint British-Irish collaboration in the humanities ever undertaken and is being supported with €1million of funding from research councils on both sides of the Irish Sea.

Professor Tom Bartlett, Chair in Irish History and principal investigator from the Aberdeen arm of the project team, said: "It's generally now accepted that around 10,000 Protestants died during the uprising, of which two or three thousand were Scots settlers.

"The details in these accounts don't come from Kings and Queens or Princes, but by ordinary folk who were caught up in the horrific events of the 1640s. They recorded what they saw, what they heard, what clothes they were wearing, whether they saw themselves as Scottish or British, and much more.

"It's an invaluable resource unparalleled anywhere else in Europe and will enable us to build up a picture of what life was like for these people on the ground. In the case of the Scots, they were recent arrivals in Ireland and had brought their own way of life and culture with them.

"The material in the witness statements, therefore, will be enormously valuable for those investigating the links between Ireland and Scotland in the 1640s, and for those interested in Scottish-Irish population movements, genealogy, material culture, linguistics and identity in the mid-17th century."

"The 1641 massacres, like King William's victory at the Boyne in 1690, have played a key role in creating and sustaining a collective Protestant and British identity in Ulster," said Professor John Morrill, from the University of Cambridge, who will chair the overall research team.

"Meanwhile in England, the rebellion and subsequent brutal conquest and subjugation by Oliver Cromwell and his colleagues has been largely airbrushed out of the collective memory.

"As G. K. Chesterton wrote a century ago, the problem with the English conquest of Ireland in the 17th century is that the Irish cannot forget it and the English cannot remember it – but we still don't know what exactly happened."

The years before the 1641 rebellion witnessed a build-up of grudges between the older Catholic population of Ireland and a new generation of Protestant settlers. The Catholic Irish upper classes particularly wanted equal recognition under their Protestant English rulers, who denied them the right to hold offices of state or serve in the military.

England was meanwhile on the brink of its own civil war. Events there – particularly plans by King Charles I to raise an Irish army to suppress a rebellion in Scotland – led to the Scots and English Parliamentarians publicly proposing to invade Ireland to subdue Catholicism. Frightened by this, a group of Catholic Irish gentry formulated a plan to seize Dublin and other towns in the name of the King.

The Catholics hoped then to force Charles to accept their demands. Instead, they were only partially successful, leading to ethnic hatred and violence, and thousands of deaths on either side.

The depositions at Trinity College Library, Dublin, tell the stories of thousands of Protestant men and women of all classes. They were collected by government-appointed commissioners and provide the chief evidence for the sharply-disputed claim that the rebellion began with a massacre of Scottish and English Protestant settlers. The library acquired the documents in 1741, but their poor condition enabled only restricted access and made them very difficult to read.

Now researchers will transcribe and digitise all 3,400 depositions, examinations and associated materials. The resulting transcripts and digitised originals will be available online for academics and the general public. They will also be published in book form.

Jane Ohlmeyer, Erasmus Smith's Professor of Irish History at Trinity College Dublin, said: "This body of material, unparalleled elsewhere in early modern Europe, provides a unique source of information for the causes and events surrounding the 1641 rebellion and for the history of 17th century Ireland, England and Scotland.

"By making it easily accessible to a wide audience it will help all traditions in Ireland and in Britain reach a better understanding of their own history."

The project has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences, and the Library of Trinity College Dublin.

Aberdeen's AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies has established itself as the leading institute of its kind in Britain.

Director of the centre, Professor Cairns Craig, added: "This very substantial award to the University of Aberdeen by the AHRC confirms Aberdeen's unique position both nationally and internationally as the leading research centre for the study of Irish and Scottish culture."

For more information on the AHRC centre at the University of Aberdeen visit http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrccentre.shtml