On the 28 November 2018, The Faculty of Advocates hosted a debate on independent legal representation (ILR) for complainers in rape trials. This was informed to some extent (as indeed is this blog) by the excellent interim report by Sir John Gillen on the law and procedures relating to serious sexual offences in Northern Ireland which was published shortly before. In many ways Sir John’s interim report is a model of what a systematic, informative and inclusive reform process should entail, engaging openly as it does with stakeholders and the public at large.

Sandy Brindley, of Rape Crisis Scotland, introduced the debate and the motion was:

‘This house believes that prosecution in the public interest cannot deliver justice to rape complainers unless they have independent representation.’

During the event a number of points were raised which have further implications and I’d like to start to explore three of them here.

1. The first issue develops from a point made fairly early in the debate by Professor Peter Duff on the increased likelihood of an appeal in the event of an application to introduce sexual history being rejected: would the presence of ILR have the same effect?

2. The second issue is related and again stems from something Duff said, this time in relation to the relatively low rate of rejections of such applications: what might this be telling us?

3. The last point picks up on a comment made by Clare Connelly QC with regard to the Not Proven verdict: would its removal as a verdict in Scots law make a legitimate or appropriate difference to conviction rates?

1. Likelihood of Appeal

If there is an increased likelihood of appeal upon rejection of an application to introduce sexual history evidence (made under section 275 of the current ‘Rape Shield’ legislation), does this mean that having ILR at the pre-trial application stage will generally cause an increase in the number of appeals due to rejected applications? Would this be a problem? If so, how much of a problem? This is part of a much bigger question and resolves I think to an issue of quantification. I will address this further below under ‘The Number of Appeals’.

There is also a follow-on question with respect to potential increase in appeals if ILR is present during the trial: what might be the trigger(s) for an appeal with ILR at trial? The notion of ILR presenting as a second or even third prosecutor (in the event of more than one complainer) at trial was discussed during the debate and this would put the defence on an increased level of alert with respect to such triggers.

The judge’s position in providing guidance and direction on the law would also come under scrutiny in terms of any reference (or possibly even lack of it?) to the ILR.

2. The Number of Appeals

Professor Duff mentioned a relatively recent study where the number of rejected s275 applications in the period under scrutiny (effectively requesting exemption from the still current Rape Shield law) was 4 out of 52. He raised this point in support of his position that the relatively low rate of rejections indicated that matters had not changed significantly since his 2011 Rape Shield paper which advocated a more robust approach by the judiciary in rejecting such applications. What could be the reason for this and why might there be an increase in the number of appeals if the rejection rate were to go up? Could it be to do with uncertainty as to the true probative value of the evidence in question at the pre-trial stage? In deciding whether to allow such applications, the judiciary must make a value judgement as to the probative value of such evidence in terms of whether it will outweigh prejudicial effects, but without knowing its relationship to, and the full extent of, the rest of the body of evidence at issue, this is arguably an unreasonable and inevitably unreasoned judgement to be made or expected at the pre-trial stage. The low rate of rejections may thus be deemed inevitable if a key driver is to err on the side of caution in terms of fair trial and ‘appeal-proof’ proceedings. I believe this may be a fundamental part of the ‘structural problem’ referred to in the course of the debate by Duff and perhaps even the true nature of the ‘systemic problem’ referred to later by Connelly.

The professor also noted some incredulity at the notion that 48 out of 52 of the s275 applications could all be legally valid, and this is the balancing side of the coin. If it is the case that only a small number of such applications are relevant and provide true probative value of significance to the verdict and sufficient to outweigh the risk of prejudicial effects then it could be argued that in the event of the implementation of a more robust approach to increasing the number of rejections, the number of appeals (or at any rate, the number of successful appeals) due to such rejections would be low. One significant problem however may be the difficulty which the ‘robust rejection’ approach presents to the judiciary in terms of imposing the possibility of deliberately rejecting applications which may have, at the pre-trial stage, unforeseeable probative value. In other words, in the absence of crystal balls, and with the inherent ethos of the judiciary being one of fairness and caution, the route of robust rejection could be a difficult one to follow. But not impossible - all with the caveat that increased numbers of appeals means increased risk of miscarriages of justice and, arguably, the imposition of a burden of proof on those who may be subject to such miscarriages.

It could be said from all this that we are seeing a perturbing, but perhaps inevitable, clash (though not an altogether undocumented one) between a number of declarations of legal and social principle and the logic of risk analysis. Such legal declarations include those expressed against auxiliary prosecutors and prejudgemental treatment, for example at paras 73 and 74 in Chapter 11 of the Auld Report (https://gillenreview.org/) and more quantitively by, among others, Blackstone.

3. The Not Proven verdict

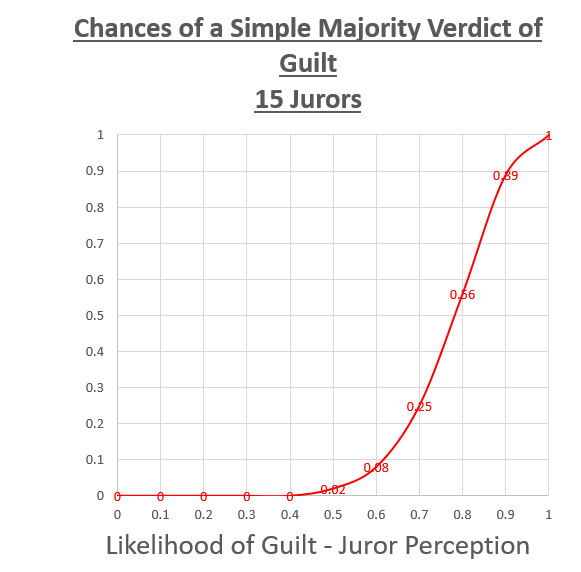

In a sidebar argument against ill-considered and ad hoc or piecemeal changes to the legal system in the hopes of bringing about improvement, Clare Connelly noted that if the not proven verdict were to be abolished, the correct vote in its absence would be one of not guilty. The underlying implication in this is that it is a mistake to believe that removing the not proven option would legitimately increase the conviction rate and that more jurors would vote guilty. Whilst Connelly’s position may be correct in theory, would it be correct in practice? In a previous blog I explored some of these ideas in relation to the current 15 juror, simple majority system in Scotland and after drawing analogies between the rate of not proven verdict outcomes and hung juries in other jurisdictions, I presented the following graphs as representing ‘a new Scots criminal law hypothesis’:

Zone of Uncertainty - The area under the bell curve was described as a zone of legitimate uncertainty.

GRAPHS of NEW HYPOTHESIS (Based on analogy with qualified majority hung jury)

The upper ‘bell curve’ graph indicating the chances of a not proven verdict can be viewed as two separate ‘S’ curves positioned back to back. Depending on the juror’s perception of the likelihood of guilt and their concept of reasonable doubt and what is beyond it, it is decidedly possible, if not probable, that group dynamics, peer pressure and other perceived pressures in the jury room would tend to polarise and split not proven voters in one direction or another – down one ‘S’ curve or the other depending on the extent of the pressures for a given direction and the will and perception of the individual juror concerned. If the general juror perception of guilt was centred on a high percentage of probability of guilt, i.e. on the cusp of being beyond reasonable doubt (around a probability somewhere above 0.9 or 90% according to some texts) it is entirely feasible that jury room pressures would polarise all of the potential not proven voters toward the ‘guilty’ verdict. Perhaps the current mock jury work being conducted by Ipsos MORI and others for the Scottish Government will provide more specific insights into these issues and perceptions. However, any teacher, lecturer or facilitator (or legal professional) who has experienced the variation in classroom or workshop dynamics from one group of people to another will surely testify to the fact that no two sets of classes, teams or other group of human beings dynamically interact or deliberate in the same way. Thus, to establish any statistical trends in these matters (if they exist) could require very large sample numbers indeed.

As yet, no interim report has been published on the Scottish Jury Research work along the lines of Sir Gillen’s Preliminary Report. The Scottish Government’s Jury Research work has however generated reports on pre-recorded evidence and structured information transfer techniques including juror note-taking, written directions and ‘routes to verdict’ guidance.

In short, in contrast to the theoretical position presented by Ms. Connelly, I think the practical likelihood of all those voting not proven, where that option exists, then voting not guilty where that option is removed, is low - but dependent on other changes to the law, for example in relation to majorities (simple, qualified, unanimous), jury numbers and comparative hung jury considerations such as jury room pressures, for example in relation to the length of time devoted to deliberation; when, for instance, might a not proven vote constitute an undecided vote?

In this respect, I do agree with her that a modern, systematic approach to legal change is required.