Jennie Riley reflects on the differences and similarities between the Spanish Flu and Coronavirus. While both pandemics saw significant restrictions on everyday life, and on death, it is harder to compare the ways in which people experienced grief – particularly when family losses are set against a broader backdrop of mourning.

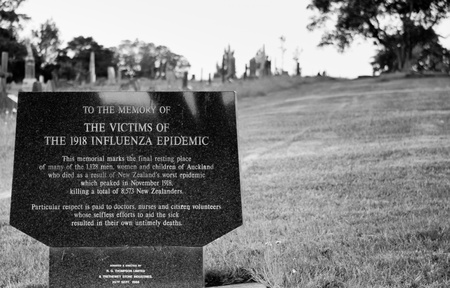

Until very recently, the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu pandemic was a historical anecdote to which few gave any considerable thought - except, perhaps, when grappling for answers in a quiz history round. And that isn’t hugely surprising – after all, as this report from the London School of Economics highlights, the only nation to have commemorated the Spanish Flu with a national memorial is New Zealand. Elsewhere, the outbreak that might rightly claim the title of ‘the Great War’s Greatest Killer,’ taking some 228,000 lives in Britain alone, has proved eminently forgettable.

Along with so many other things, the Coronavirus outbreak has changed that. Comparisons across the intervening century have been regularly found in our news feeds.

It’s important to emphasise that 1918 was a very different context to 2020: Britain had no NHS, nor a World Health Organisation to refer to, and a much less developed grasp of virology and public health. Indeed, there was uncertainty and disagreement about what the Spanish Flu was. Where the COVID-19 outbreak has posed particular risks to the elderly and medically vulnerable, the Spanish Flu disproportionately affected those in their twenties and thirties, especially women. As the LSE's Dr Martin Bayly suggests, the widespread rhetoric that compares tackling Coronavirus to being engaged in war would have fallen on deeply cynical ears for those living in the long shadow of World War 1.

Yet when we explore bereavement and funerals, we might tentatively draw some helpful parallels between the Spanish Flu and Coronavirus.

During the Spanish Flu caring for the dead was challenging and complex: then, as now, there were concerns that funeral directors, morgues and graveyards would become overwhelmed. In some cases they were: for example, Sunderland reported a distressing backlog of hundreds of corpses which could not be buried for over a week. In some areas, funerals were conducted dawn to dusk – or even into the night - in order to keep up. In others, hearses and graves hosted multiple bodies. While funerals were never prohibited, they were certainly profoundly affected by restrictions brought in to manage the pandemic.

While it is relatively easy to compare public health and death management approaches, it is much more difficult to compare national mood, individual experience, and grief. As Professor Douglas Davies of Durham University explains, it is easy to see a ‘family likeness’ of grief across the apparent divides of both time and location, which points to commonalities (though not necessarily universal) in how humans respond to death and experience the loss of a loved one. Equally, though, he calls for ‘explanatory subtlety,’ for it is important not to lose sight of important differences in context, expectations and norms when we consider death (see page 222 of his 2015 Mors Britannica). Perhaps what we can say with confidence is this: for every large-scale tragedy, there will always be personal experiences. While the two are concurrent, they may not always cohere.

Bayly describes the'fatalism' which characterised the British national response to the Spanish Flu outbreak, matched with an 'absence of public grief.’ Both can be linked to the post-war context, in which such immense losses had already been suffered. Yet if we look at individual accounts, the picture is more emotional and nuanced. This BBC News article draws on research by Dr Hannah Mawdsely, who studied a collection of some 1700 first-hand accounts of the Spanish Flu in Britain. These include the story of a nine-year-old who lost her mother and sister two days apart. She explained, “It really was a terrible time, not knowing who we were going to lose next.” There are echoes in this short account of successive loss in BBC reporter Cathy Killick's account – published on 17th February 2021 – of losing both parents to Coronavirus. Mawdsely also notes survivors’ painful recollections of grave-diggers and coffin-makers struggling to keep up with demand, and funeral corteges becoming a constant parade through the centre of many towns. But personal experiences are not so well recorded by history. Indeed, Bayly comments on this, suggesting that “[e]ven though funerals were permitted, the sheer pace of death fostered a silencing of grief.” Donald Joralemon, an anthropologist in the USA, has made similar observations of national memorials to mass loss on the other side of the Atlantic: questioning the assumption that such memorials are always a means of turning a tragedy into something hopeful and positive which can help ‘heal’ the nation, he also observed that individual bereaved families often found the process of design and, on occasion, the resulting artefacts, served only to make their own grief feel insignificant.

Is there a parallel to be drawn with Coronavirus? Perhaps. While it perhaps doesn’t amount to a shared ‘fatalism’ (though LSE’s Dr Katharine Millar quite rightly criticises the UK Government’s crisis narrative for passing certain deaths off as ‘inevitable’) there is certainly a sense of weariness amidst daily recounts of death statistics. For example, on 17th February – the same day as Cathy Killick’s story was published, the BBC ran an article with the headline ‘Covid deaths: If the news leaves you numb, you’re not alone.’ Certainly at times I’ve felt desensitized, and can’t help but recall the infamous Stalin quote – that ‘If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.’

But part of the reason that quote has kept resonating throughout the pandemic is because there have been moving stories about personal loss and distress everywhere - from social media feeds to the BBC’s home page. These accounts capture the complex and varied emotions and experiences of dealing with death during a pandemic. They have included painful stories of funerals and commemorations curtailed and cut short. Some have discussed the challenge of handling personal grief and the unprecedented national situation at the same time. In April 2020, Radio 4 broadcast a funeral poem penned by Dorothy Duffy in honour of her sister, entitled ‘My Sister is not a Statistic,’ capturing something of the difficulty of claiming one’s own loss as unique, and the loss of a unique person, while the public narrative is one of a collective, shared loss. There have also been uplifting tales of support found among those who have shared similar experiences, who can help one another to navigate between a profoundly public trauma and deeply intimate loss.

The parallels to 1918 need to be made more carefully here: while individuals would certainly have had a sense of the pain of their own losses, and the losses of those nearby, there was no equivalent to the public broadcasting of individual stories that we’re experiencing thanks to the likes of BBC news. Will attempts to juxtapose the statistics with the individual tragedies alleviate the ’silencing’ that Joralemon and Bayly both identify? This is one of the things we hope to explore in this research project.

There will be profound lessons to learn from Coronavirus that touch every aspect of society – including death and grief. The team at LSE has valuably highlighted the importance of doing better than we did in 1918 in terms of public commemoration. They conclude that “[t]he difference that public commemoration may have made to preparedness in later pandemics is a key counter-factual and arguably provides one of the most compelling ‘lessons’ from the 1918 pandemic.”

In what we hope will be a complementary way, our research team hopes to learn from Coronavirus by exploring its effects among individuals, families, and groups of friends, and considering how we can best care for them and the individuals lost, both in times of national crisis and beyond them. It was stories of funerals, memorials and death-rites disrupted that inspired the project, and we hope to collect more, learning from them in order to improve the ways in which we might care for people through funerals. But perhaps we might also learn lessons about how best to care for individuals when their loss is so dramatically set against the backdrop of shared crisis.

Please click here to take you back to the Care in Funerals website.

Please note, all comments will be moderated so may not appear immediately. If you wish to remain anonymous in your comment please put down initials or solely a first name.

There seems to be no research of the trauma suffered by those who could not get into care homes, nursing homes and the hospitals. I only got to see my husband through a window at the Nursing Home every day for 9 months and only got in 4 hours before he died of the Virus. This Nursing Home was costing an astonishing £6,000 a month and they kept telling me I could not get in in case I gave him the virus but it was then that gave him the virus and killed him.

I think there must be a lot of people like me who are severely traumatised by not getting into care homes, nursing homes and the hospital. I know someone who didn't see his mother in person for a year because she was in a nursing home and only got to see her through and window and never got to see his mother ever again because she died in the nursing home and they wouldn't let him in to be with her. I am surprised that no research has been done on this vital aspect of bereavement because this is a grief like no other since when my mother and father were dying I at least got to be with them but only getting to see someone you love through a care home or nursing home window has a profound and everlasting traumatic effect I should think on all of us who were not allowed in care homes, nursing homes and the hospital. It was inhumane not to let us in. The staff were giving the care home and Nursing Home residents the virus as well as people being transferred from hospital without even being tested for the virus. It is incredible that anyone with any common sense would have transferred them without testing them for the virus. Many of us are left heart broken for the rest of our lives over the inhumane way the virus was dealt with. Sweden did not have a lock down and yet had far less deaths than Britain. I will remain Heart broken forever.

Thank you for your comment, Fiona. It is still shocking to hear about these traumatic events. We are very sorry you have been through such profoundly awful experiences and continue to feel heartbroken as a result.

Our research project focused on disruptions to funeral provision in the first years of the pandemic, so we did not examine in depth people's experiences of being unable to spend time with relatives in care homes or nursing homes. We did, however, hear from some people who found that being unable to hold a full funeral compounded the distress of not being able to be with a relative when they died. When funerals were less constrained, we also heard from people who tried to give someone an extra good send off at their funeral because they had been unable to give the care they wanted to as they died.

Your account is an important testament to such difficult experiences. Thank you for sharing it. You're right that we should be collectively learning from all of the pandemic's challenges.

With best wishes, Vikki and Jennie, on behalf of the project team.