Around 70 museum collection items at the University of Aberdeen come from Sierra Leone. It is one of the most significant African collections at the University, alongside those from Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Malawi. Most of the collection has been in Aberdeen for over 100 years, and our historic records for many of the items unfortunately provide little detail on the circumstances of how the University acquired them. But we do know that many of the items were brought to Aberdeen during the period when much of Sierra Leone was a Protectorate under British colonial administration. The largest bequest consists of twenty items that were given to the University by a Mrs Hugh Ross in 1913. This blog post will explore one item in particular, and the woman who owned it: the snuff box of the Mende kor mahei (war chief) Madam Yoko.

"Map of the West Coast of Africa" Compiled from official documents, By John Arrowsmith. 1843. London

Snuff box that "belonged to Madame Yoko, late chieftainess of Mendi tribe" - presented by Douglas M. Spring, 1907." ABDUA:7140

Colonialism in Sierra Leone

In Madam Yoko’s time, the interior of Sierra Leone was a British Protectorate (from 1896 to 1961), meaning that it was incorporated into the British Empire, while retaining local systems of indigenous leadership autonomy. Prior to that, there had been a colonial presence in the country for around a century. A colony had first been established in 1787 by the slavery abolitionist and philanthropist, Granville Sharp, and the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor in London. It was intended to be a settlement for formerly enslaved people. This early colony fared poorly, and was destroyed in a dispute with the local Koya Temne in December 1789. Granville Sharp resurrected the colony as a stock company, the Sierra Leone Company (SLC). In 1808, Sierra Leone became a Crown colony, so was ruled by a governor chosen by the British monarch.

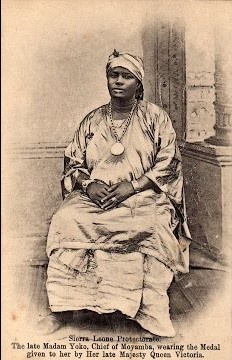

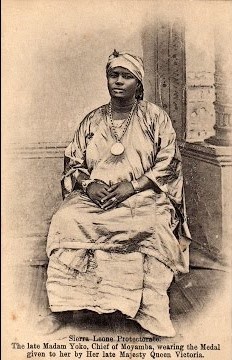

Madam Yoko

Madam Yoko is a complicated figure due to her relationship to the British colonial government in Sierra Leone. She is also an interesting example of a powerful woman, of which there are a great many referenced in historic scholarship on Sierra Leone.

Madam Yoko did not become Madam Yoko until later in life. As a child, she was called Soma. Only when she was initiated into the Sande society – a women’s initiation association – did she attain adulthood in Mende society and her adult name, Yoko.

In some regions the female initiation society is known as Bundu instead of Sande. Three items in Aberdeen’s collection are identified as Bundu. One is shown on the right.

Female figure, carved in wood, with waist-band of glass beads and loin cloth in red cotton. Bundu, although described in Reid’s 1912 catalogue as Ashanti. ABDUA:7153

Madam Yoko's ascendance to power

As cultural associations that defined gender identity, the Poro and Sande supported female chieftancy and women taking on roles of political power. Madam Yoko’s ascendance to power came in part as a result of three marriages. Her third marriage was to the famous kor mahei, Gbanya, who founded the town of Senehun. He had established himself as head of the Kpa Mende confederacy, a loosely-affiliated group of chieftanices. But when a British colonial policemen publicly flogged Gbanya in 1875, his power started to wane. On his death in 1878, Madam Yoko took over. She filled a role as mediator between chiefs of the confederacy and the colonial government. In 1882, Governor Havelock of the Colony of Sierra Leone appointed her to oversee Senehun. Her superior in the region, Mohvee, died in 1884 and she took over, aligning herself with the British.

Remembering Madam Yoko: Sierra Leone at 60

Because of her close association with the British colonial government and their support of her as ‘Queen of Senehun’, Yoko was forced to flee from her own people during the Hut Tax War. The British government, grateful for her loyalty to the British Crown in this conflict, declared her a Paramount Chief, and Queen Victoria awarded her a silver medal. She served as Paramount Chief for another eight years, and died in 1906. Madam Yoko’s snuff box was presented to the University by Douglas M. Spring in 1907, one year after her death.

Madam Yoko is today memorialised throughout Freetown, with a large image of her on the Sierra Leone National Museum, and a luxury hotel named after her. In April of 2021 Sierra Leone marked the sixtieth anniversary of independence and Madam Yoko featured in some of the commemorations as a symbol of pre-colonial female leadership, albeit one whose relationship with British colonialism was complex.